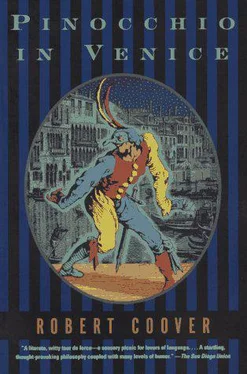

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And so they have disembarked there on the stormy Molo, the ancient sojourner solicitously chaired in a traditional Venetian portantina, and made their way into the Piazza, Eugenio shouting: "Make way! Make way! Largo per un gran signore!" — though he cannot be sure, buried in blankets and blinded by the freezing wind, that there is actually anyone out in this wretched weather but themselves. He seems to hear voices and is dimly aware of passing under lamps and illumined façades, perhaps the Basilica itself, but his senses, he knows, can no longer be trusted, for he also seems to hear the murderous cries of squealing assassins, angels fluttering and making rude windy noises overhead, and a little whistlmg sound inside his skull as though something might be boring away in there, and the blur before his eyes is throbbing as though his pulse were beating on him from without. Even inside all his blankets, he is trembling violently, and his tears, shed on his dear friend's breast, have frozen on his face, threatening to split the exposed parts of his cheeks open. He feels light-headed and heavyhearted all at once, as though his bodily parts were trying to go in two different directions at the same time. It is not unlike the sensation he had while drowning in the canal, and he wonders, in his feverish confusion, if he might not still be down there, sinking into the slime, this rescue but a dying dream.

Or worse. Perhaps his whole rational human life has been nothing more than the dying dream of that poor drowned donkey, maybe he has only imagined that conveniently ravenous shoal of mullets and whiting, all the heroics thereafter and the transfiguration and the lonely century that has followed being just so much wishful thinking, certainly it all seems to have passed in the blinking of an eye, yes, maybe, all illusions aside, he is fated to be a drumhead after all, one more noseful and the mad dream over. He takes a deep snort: no, no such luck, just more frosty air, faintly Venetian-tinted, it has not yet, whatever it is, stopped going on

"Ah, Pini, still with us! Good boy!" enthuses Eugenio at his side. "Coraggio, dear friend, we are almost there! But, ah! what a splendid night this is, a pity you're under the weather! It reminds me of the first night I came here all those years ago! It was snowing then, too, and dog-cold, but we were young and Carnival had begun, so what did it matter? No one to drag us in to baths and books, no one to make us keep our caps and scarves on, our pants either for that matter! Who could be happier, who could be more contented than we?"

The professor, too, is thinking, deep down inside his fever, where thinking is more like pure sensation, about happiness, and about all the pain and suffering that seems needed to make it possible. Everyone loves a circus, but to make the children laugh, his master whipped him mercilessly and struck him on his sensitive nose with the handle of the whip, so dizzying him with pain (yet now, when his thoughts are more like dreams, he knows — and this knowledge itself is like a blow on the nose — he was as happy as a dancing donkey as he has ever been since) that he lamed himself and so condemned himself to die. And as for that country fellow who tried to drown him, he was at heart a gentle sort who dreamt only of a new drum for the village band. No doubt some other donkey, even more ruthlessly treated, was eventually slaughtered for the purpose, maybe even someone he knew, because: who would want the village band to be without a drum?

"Oh, the lights then! the extravagant music and endless gambols! In the streets there was such laughter and shouting! such pandemonium! such maddening squeals! such a devilish uproar! It was like no other place in the world! It is like no other place in the world, Pini! What fun it is still!"

But should we, he asks himself, rising briefly out of the pit of his present distress, resisting the seductive lure of donkey thoughts, should we, aware of all the attendant suffering, deny ourselves then the pleasure of the circus, of the drum? Or should we, knowing that none escape the pain, not even we, seize at whatever cost (here he is seized by a fit of violent wheezing and coughing as though there were something caustic in the atmosphere, not unlike the foul air at faculty meetings) what fleeting pleasures, life's only miracles, come our way? In short, somewhere, far inside, something (what is it?) faintly troubles him

"And look, Pini! Look how beautiful!" Eugenio exclaims, tenderly patting away the coughing fit. "See how the snow has been blown against the buildings! It's like ornamental frosting! Every cap capped, every tracery retraced, the decorative decorated! It's like fairyland! The Moors on the Clock Tower are wearing lambskin jackets tonight and downy cocksocks on their lovely organs and all the lions are draped in white woolly blankets! The snow is at once as soft and fat as ricotta cheese, yet more delicate in its patterns than the finest Burano lace! And now, do you see? in the last light of day, it is all aglow, it is as though, at this moment, the city were somehow lit from within! Look, Pini! O che bel paese! Che bella vita!"

Having been ever, or nearly ever, the very model of obedience, a trait learned early and the hard way at the Fairy's knees, or, more accurately, at (so to speak) her deathbed, or beds, the old scholar cannot risk, in his own extremity, changing his stripes now (though that is, he is all too dizzyingly aware, the very nature of his extremity), so he does his best to respond to the wishes of his old friend and providential benefactor who clearly loves him so, poking his nose into the wind and nodding gravely, even though to his fevered eye it is a bit like gazing out upon a photographic negative, the ghastly pallor of the snow-blown buildings more a threat than a delight. All the towers and poles in the swirling snow appear to be leaning toward him as though about to topple, lights flicker in the multitudinous windows like chilling but unreadable messages, and the Basilica itself seems to be staring down at him as though in horror with fierce little squinting eyes above a cluster of dark gaping mouths, its familiar contours dissolving mysteriously into the dimming confusion of the sky above. All around him there is some kind of strange temporary scaffolding going up like hastily whitewashed gibbets. Blood red banners, stretched overhead, snap in the wind, a wind that tugs at the umbrellas of the few scattered early evening shoppers still abroad, stirs their furs, and whips at the tails of their pleated duffle coats. Pigeons, dark as rats, crawl through the trampled snow, no longer able to fly, their feathers spread and tattered, chased by schoolboys who pelt them with snowballs, aiming for their ducked gray heads.

"No!" he wheezes, struggling to rise up within his bonds. "Stop stop that — !"

"Ah, the mischievous little tykes," chuckles Eugenio. "Reminds me of our own schooldays, Pini, when we used to trap the little beggars with breadcrumbs, tie their claws together, and pitch them off the roof to watch them belly-flop below! What times we used to have — !"

"I never did!" he croaks. "I loved pigeons! Don't do that, you young scamps! Stop it, I say!"

A boy near his litter looks up at him, grinning, his narrow eyes aglitter, his mittened fists full of snow. He drops the snow, reaches up, and pulls on the professor's nose. When it doesn't come off, he backs away, the grin fading. His eyes widen, his mouth gapes, then, shock giving way to horror, he runs off screaming.

"Ha ha! Well done, Pinocchio!" Eugenio laughs, as the boy, crying out for his mother, goes sprawling in the snow. "You haven't changed a bit!"

"Pinocchio — ?" askes a feeble voice below. A dull gray eye blinks up at him from a crumpled mass half-buried in the snow. Eugenio has gone over to pick up the small boy and brush him off, giving him a number of kindly little pats and pinches. "Is that Pinocchio?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.