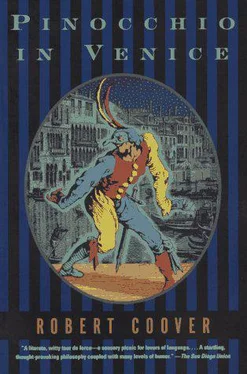

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Gladly, master, but my instructions were to stay at my post while drying you out in the sun."

"No, no, I didn't mean you! I was only recalling a flight "

"You wish to fly, master — ?"

There is something wrong with this memory. Something out of his recent ordeal that he does not wish to recall. Or, better said, that he has simply forgotten, and probably a good thing, too, he needs to put all that behind him like Eugenio says, his recovery may depend upon it. Three café orchestras are playing all at once this morning, their whimsical cacophony interscored with the clangor of the city's multitudinous bells, the blast of recorded music, the whistling of hawkers and the honking of gulls and boats, the shouting and laughter in the square, the grinding of the clock mechanism beside him, all of it echoing and rebounding off the glittering waters of the lagoon like a single clamorous voice, which even he can hear in spite of having lost his ears, a voice which seems to insist upon the dominion of the present. Above him, the two huge bronze figures, known popularly as "Moors" because of their shiny black patina and their legendary genitalia, pivot stiffly and hammer out the morning hours, while, beneath them, under the symbolic Winged Lion of St. Mark with his stone paw on an open book and the copper Virgin and Child on their little terrace, the great revolving face of the zodiacal clock celebrates eternity with its serene turnings even as it intransigently mills away the passing moment, turning history into a kind of painting on the wall. "It is a devilish priest's game not worth the candle, a charade of charlatans, am I right?" hisses Marten the servant, keeping up his subversive pissi-pissi in his ear. "History! Hah! It is a veritable shit storm, master, punto e basta!"

"But, no, I was wrong then, you see " For in time, tutored by Giorgione and by his beloved Bellini, he came to recognize that, if there were pure and impure thoughts, there were also simple and complex ones, and pure complex thought, which he was increasingly given to (he had taken on flesh, after all, he was no longer a mere stick figure), was obliged to embrace the impure world, else, blinkered, it found itself jumping, again and again, through the same narrow hoop.

"Uhm, excellent way to break a leg, padrone."

"Oh, I know, I know "

"Or, heh heh, a neck "

Moreover, as he himself had been a sort of walking parody of thought given form, assuming that what was in old Geppetto's pickled head was so noble a thing as to be called thought, he had been able to intuit (here, perhaps, the years in Hollywood helped) the hidden ironies in all ideal forms, and so began to perceive that thought's purity lay not so much in its forms as in its pursuit of those forms — whereupon: his "go with the grain" as a moral imperative, "character counts," his symbolic quest for the Azure Fleece, the concept of I-ness, "from wood to will," and all that. Already, in Art and the Spirit, erroneous as it might have been in its refusal to acknowledge the theatrical in Venetian art (what, he was obliged to admit, was the "emergence of archetypes from the watery atmosphere like Platonic ideas materializing in the fog of Becoming" but pure theater, after all pure stage hokum?), he had begun, if not wholly to accept ("Ebbene, I too am interested in archetypes, condottiero "), at least to understand and respect Palladio's position, and if he was once impatient, he was now more sympathetic, more prepared to make room for the human condition. Which was his condition, too more or less

" Provided the little stronzos are edible!" And Marten snatches, or seems to snatch, at a passing pigeon, throttle it, and stuff it into a bag at his side.

"Of course, it might just be my weakened eyesight "

"Eh?"

Thus, from his lofty Clock Tower perch, coped and hooded in thick cashmere blankets with only his nose poking out, the old professor peers out upon this luminous spectacle and, face to face with Palladio's pale sober San Giorgio Maggiore across the sun-glazed bay, muses, his own pale and sober thoughts punctuated by the thick fluttering of pigeons and the rude interruptions ("Eh? Eh?") of Eugenio's impertinent servant, upon the folly of his youth and the debilities ("That fog, I mean ") of old age. Which, it would seem, contrary to his expectations of just a few nights ago, is not yet over. Like this crumbling old city, these famous "winged lion's marble piles" ("A damned nuisance, I can tell you, and no bloody cure for them either," he hears somebody grumble, might be Marten, he can't be sure) now scattered out before him in their antique devastation — pocked, ravaged, bombed, flooded, tourist-trampled, plague-ridden, pillaged, debauched, defaced, shaken by earthquake, sapped and polluted, yet somehow still stubbornly, comically afloat — he too, perversely, lingers on. Little more than, perhaps, but if by some misfortune he is not yet dead, as one of his doctors so wisely put it that night of Eugenio's rescue, then it's a sure sign he's still alive.

He had awakened, having apparently passed out in the Piazza, a Piazza he could not however at that moment recall (even now that bitter night with its monstrous snow-frosted shapes looming over him in the swirling wind like howling ghosts is little more than a half-remembered nightmare, in no way resembling the cheerful scene spread out before him now), in a soft warm bed piled high with down comforters, a hot water bottle at his feet, and three doctors at all his other parts, probing and prodding with various tools of their trade and debating the particulars of his imminent demise.

"It is my professional opinion," said one solemnly, flicking the old pilgrim's tender nose back and forth as though testing its reflexes, "that he is dying from top to bottom, or else from bottom to top, though one could conceivably hold the position that death was rapidly overtaking him, both inside and out."

"I quite disagree!" exclaimed a second, lifting a foot by a toe that snapped off like a dry twig. "You see? His condition is clearly as desparate at one end as at the other, even if the surface is as moribund as the core!"

"Gentlemen! Please!" protested Eugenio, who, for a confused moment, the dying scholar mistook for his old friend and benefactor Walt Disney with his apple red cheeks and pussycat voice and sweet soft ways, oily as whipped butter. "Is there no hope?"

"Well," sighed the first, pressing a stethoscope to the place where an ear used to be and rapping the professor's feverish brow speculatively, "if he is not dead by midnight, he may live until tomorrow."

"How can you say that?" cried the second, sticking a thermometer in his peehole, and glaring angrily at his watch. "He will certainly not live until tomorrow, if he is dead by midnight!"

"And have you nothing to say, sir?" Eugenio asked, turning to the third doctor.

"This face is not new to me!" that personage responded, pointing at the place where others might have a navel and he but a knothole. "I know him for a perfidious rogue and a shameless ideomaniac, buono a nulla, this faithless figlio di N.N., this good-for-nothing whoreson legno da catasta! Fortunately, all knots come to the comb, and to the lancet as well, this one no exception, so out with it, I say! Gentlemen, hand me my brace and bit!"

"Wait!" cried the first doctor suddenly, drawing back. "Could it be — not being otherwise, that is — the plague?"

"It might be," gasped the second, wiping his hands nervously on his trousers, "but then again, if it isn't, it's assuredly not!"

"Oh woe, woe, WOE!" exclaimed the third doctor, beating his chest and gazing upon the patient in horror. Certainly he could not have been a pretty sight, his hide foxed and tattered and falling away, bits and pieces of him missing altogether, his miserable water-soaked body wracked by fever and a rasping cough — as Eugenio remarked wryly when first seeing his eyelids flutter: "Behold, gentlemen, there is the man who has been in Hell!" In truth, in his condition the plague might have been a mercy. "As one who has had it hammered into him by bitter experience," the third doctor continued, clubbing his own pate with a balled fist, "let me assure you that neither earth, nor air, nor water, nor flesh itself is a safe refuge for wicked little philosophasters under the lignilingual curse!"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.