He'd finally turned facing her through a gasp of smoke, sunk back against the table length litter of papers, books, folders, dirty saucers, a coffee cup, a shadeless lamp. — It's simply a man I've known for a number of years, he said, — nobody there, he's out of the country. Now I don't want to keep you, you said you had an appointment and I've got a good many things here to…

— Yes I didn't mean to pry, it's just… she backed off to the door, — I mean I don't blame you, living alone here for two whole years with everything like, everything just waiting like the silk flowers in there when you come down the stairs wait, oh wait I just thought of something before you start what you're doing wait, I'll get it… and she left him reaching down a thumbprinted glass from a bookshelf, pulling the bottle from the paper bag in the raincoat pocket and pouring a level ounce. He'd emptied the glass, made another cigarette and lit it at the sound of her down the stairs, the lines of her lips more clearly drawn now and those on her lids at less hazardous odds she came into the kitchen holding out the worn address book. — It was in the trash, it looked important I thought…

— Do you go through my trash?

She'd stopped short, across the table where he seized it from her — I didn't mean, I thought maybe you'd thrown it away by mistake it looked…

— It's, all right he muttered, standing twisting the thing in his hands as though he might have said more before he turned for the trash to drop it in, and then he paused, bent over, reaching down into the trash after it — here, you don't mind if I rescue this?

— No wait don't not that no I, wait… She caught the corner of the table, flushed, — oh… getting breath, — oh. He'd straightened up with the Natural History magazine.

— I thought you'd thrown it out.

— No that's all right yes, yes for that story about, on the cover? you said they steal cattle? And her sudden urgency seemed to weigh everything on his response, the Masai and their cattle raids, as though right now in this kitchen, clinging to the table corner, nothing else mattered.

— Well, well yes, he said — they, it's their ancient belief that all the cattle in the world belong to them. When they raid other tribes they're just taking back what was stolen from them long ago, a good serviceable fiction isn't it… He held the magazine out to her — you might want to read it? It's not what I want anyhow, there's a piece here on the Piltdown fraud I can just tear it out and…

— That's all right no, no keep the whole thing please. I, I just wish I could stay and talk to you, do you know what time it is? The clock stopped last night and I…

— It's two twenty, he said consulting no more than her hands seizing one in the other, following her haste through to where her coat lay flung over the newel.

— I won't be back till after dark/ I mean it gets dark so early now but if you need anything, if your work keeps you here I mean there's food in the refrigerator if you, if you get hungry before you go… She reached for the coat but he already had it, holding it up for her — because I won't get home till it's dark and that, Halloween out there, if they did that last night… she'd turned, a hand back to hold her hair up away from the sudden glint of perspiration beading the white of her neck where he settled the collar, — what they'll do tonight… All she'd get tonight would be the little ones in costume he told her, getting the door open on the blown leaves, the disconsolate streamers, the shaving cream exhortation across the black stream of the road where he watched her hesitant step down as one into the chill of unfamiliar waters, watched her down past the carrion crow raising scarcely a flutter before he pressed the door closed for the snap of the lock.

Then he stood there, his gaze foreshortened to the stitched silence of the sampler's When we've matched our buttons… and when he did turn it was to walk over to the alcove and stand there looking out; to pause over the cyclamen, flick its silk petals for dust; to stand running a hand over the rosewood curve of a dining room chair looking over the plants, looking out past them to the unraked lawn, pressing a loose moulding into place with his foot each step, coming through to the kitchen, retracing steps leading him back through the sliding door to stand, where he could approach them close enough, reading the titles of books, taking one down to blow it off and replace it or simply run a finger down the spine, before he got over to light another cigarette and spread another folder on the litter before him. There he turned papers, removed one, dropped another crumpled into the Wise Potato Chips Hoppin' With Flavor! carton at his feet, folded, tore, made another cigarette put down beside one still smouldering in the yellowed dip of marble at his elbow shattering its still blue curl of smoke with an abrupt exhalation of grey to stare at a page, at a diagram, a map detail, a torn shred of newspaper already yellowed and he was up again, staring out through the clouded pane at the halting drift of the old celebrant out there, broom and flattened dustpan going on before, his wavering course to the dented repository ahead broken by doubtful pauses, getting his bearings, gaping aloft at faith stretched fine in the toilet paper celebration overhead. Inside there he poured another ounce of the whisky and went back to the kitchen, to the dining room, stopping to square the table and draw the chairs up even around it, putting his hands on things, till finally his steps took him mounting the stairs themselves and down the hall to the open bedroom to stand in its doorway looking, simply looking at the empty bed there. He'd come back up the hall, past sodden mounds of towels, socks, a long glimpse in at the white frill there in the bathroom basin when something, a movement no more than the flutter of a bird's wing, caught his eye through the glass at the foot of the stairs and he stepped back. Then the sound, no more than the sharp rustle of a branch, and the door came open, went closed again on the figure abruptly inside, one small hand on the newel like something alighted there. — Lester?

— What are you doing here.

— You didn't know? It's my house… He came out on the stairs, — you should have told me you were coming, saved you some trouble… and down them, — you could have been up on a morals charge.

— What are you talking about.

— The ladies' room at Saks.

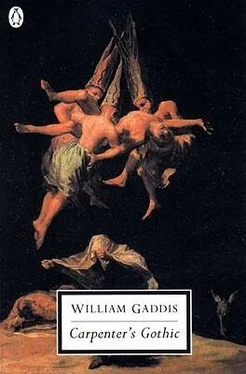

— Still getting it all wrong aren't you, McCandless… and in fact the plastic card he'd sprung the lock with was still in his hand. — Always getting it wrong… and the card went thrust into a pocket of the speckled tweed jacket that seemed, from behind now, to draw the narrow shoulders even more close as he stood by the coffee table looking about. — Interesting old house, you know what you've got here? the head cocked this way, that, — it's a classic piece of Hudson river carpenter gothic, you know that?

— I know that, Lester.

— All designed from the outside, that tower there, the roof peaks, they drew a picture of it and squeezed the rooms in later… darting now along the line of the ceiling moulding to the crumbled plaster finial where it met the alcove's arch, — you've got a roof leak there… as though he'd come to give an appraisal, come up to buy the place, — have it fixed before it gets worse. You getting into the redhead?

— You should have asked her.

From the alcove back to the chimneypiece and down, his steps followed his glance through to the kitchen as the phone rang and he stood there at the table studying the smudges, crosses, hails of arrows till it stopped ringing. — She got kids?

— You should have asked her.

And at the sliding door now, — I thought you were neater than this, McCandless. What was this, the garage? He stepped in over the cascaded books, a carton marked glass, fluttered a hand up to stir the still planes of smoke. — I thought you were going to quit those cigarettes… He turned half perched on the edge of an open filing cabinet. — You see these white doors from the outside, it still looks like a garage. Who did all the work in here, put in all these bookshelves, you? But all that came back was a puff of smoke, a hand reaching past him for the thumbprinted glass. — You know that's the worst thing you can do at your age? the cigarettes and the whisky? They work together, kill the circulation. Lose a couple of toes and you'll see what I mean.

Читать дальше