Hunting down pedestrians is part of daily routine in big Latin American cities, where four-wheeled corsairs encourage the traditional arrogance of those who rule and those who act as if they did. A driver’s license is equivalent to a gun permit, and it gives you license to kill. Ever more demons are ready to run down anyone who crosses their path. On top of the traditional thuggery, hysteria about robberies and kidnappings has made it more and more dangerous, and less and less common, to stop at red lights. In some cities stoplights mean, Speed up. Privileged minorities, condemned to perpetual fear, step on the accelerator to flee reality, that dangerous thing lurking on the other side of the car’s tightly closed windows.

In 1992, a referendum was held in Amsterdam. People voted to reduce by half the already restricted area where cars can circulate in that kingdom of cyclists and pedestrians. Three years later, Florence rebelled against auto-cracy, the dictatorship of cars, and banned private vehicles from its downtown core. The mayor announced that the prohibition would be extended gradually to the entire city as streetcar, subway, and bus lines and pedestrian walkways expanded. And bike paths, too: according to plans it will be possible to pedal anywhere in the city safely, on a means of transportation that is cheap, runs on nothing, and was invented five centuries ago by a Florentine, Leonardo da Vinci.

Modernization, motorization: the roar of traffic drowns out the chorus of voices denouncing civilization’s sleight of hand that steals our freedom, then sells it back to us, that cuts off our legs to make us buy running machines. Imposed on the world as the only possible way of life is a nightmare of cities governed by cars. Latin America’s cities dream of becoming like Los Angeles, with its eight million cars ordering people about. Trained for five centuries to copy instead of create, we Latin Americans aspire to become a grotesque imitation. If we are doomed to be copycats, couldn’t we at least be a little more careful about what we choose to copy?

At night, I turn on the light to keep from seeing.

— HEARD BY MERCEDES RAMÍREZ

LESSONS FROM CONSUMER SOCIETY

The punishment of Tantalus is the fate that torments the poor. Condemned to hunger and thirst, they are condemned as well to contemplate the delights dangled before them by advertising. As they crane their necks and reach out, those marvels are snatched away. And if they manage to catch one and hold on tight, they end up in jail or in the cemetery.

Plastic delights, plastic dreams. In the paradise promised to all and reserved for a few, things are more and more important and people less and less so. The ends have been kidnapped by the means: things buy you, cars drive you, computers program you, television watches you.

GLOBALIZATION, GLOBALONEY

Until a few years ago, a man who had no debts was considered virtuous, honest, and hardworking. Today, he’s an extraterrestrial. Whoever does not owe, does not exist. I owe, therefore I am. Whoever is not credit-worthy deserves neither name nor face. The credit card is proof of the right to exist; debt, something even those who have nothing have. Every single person or country that belongs to this world has at least one foot caught in this trap.

The productive system, which has become the financial system, multiplies debtors to multiply consumers. Karl Marx, who saw this coming over a century ago, warned that the tendency of the profit rate to decline and the tendency of production to overproduce would oblige the system to seek limitless growth and to extend an insane degree of power to the parasites of the “modern bankocracy,” which he defined as a “gang” that “knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it.”

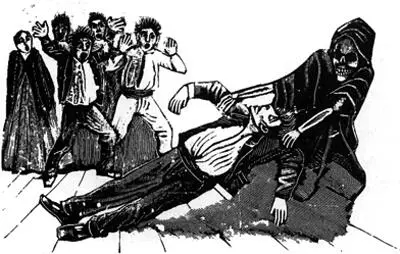

Today’s explosion of consumption makes more noise than all the wars that ever were and causes a greater uproar than every Mardi Gras in the world happening at once. As the old Turkish proverb has it, he who drinks on credit gets twice as drunk. This fiesta, this great global binge, makes our heads spin and clouds our vision; it seems to have no limits in time or space. But consumer culture is like a drum: it resonates so loudly because it’s empty. At the moment of truth, when the clamor ceases and the party’s over, the drunk wakes up and finds himself alone, accompanied only by his shadow and the broken dishes for which he must pay. The system that drives demand and obliges it to expand also builds walls for it to crash into. While the system needs markets that are ever broader and more open, the way lungs need air, at the same time it requires raw materials and human labor that are cheaper and cheaper. This system speaks in the name of all, to all it directs its imperious orders to consume, among all it sows the buying fever. But it won’t do: for nearly everyone, this adventure starts and ends on the TV screen. Most people who go into debt in order to have things soon have nothing more than debts taken on to pay debts that lead to more debts, and they end up consuming fantasies that only come true by stealing.

Poverties

Truly poor people have no time to waste time.

Truly poor people have no silence and can’t buy it.

Truly poor people have legs that don’t remember how to walk any more than chicken wings remember how to fly.

Truly poor people eat garbage as if it were food and pay for it.

Truly poor people have the right to breathe shit as if it were air and not pay for it.

Truly poor people have the freedom to choose — between one TV channel and another.

Truly poor people live passionate dramas with their machines.

Truly poor people are always cheek by jowl and always alone.

Truly poor people don’t know they are poor.

With the massive growth of credit, warns sociologist Tomás Moulian, Chile’s everyday culture has come to revolve around symbols of consumption: appearance as the essence of personality, artifice as a way of life, “utopia on the installment plan.” Consumerism has been imposed bit by bit, year by year, ever since Hawker Hunter jets bombed Salvador Allende’s presidential palace in 1973 and General Augusto Pinochet inaugurated the era of the miracle. A quarter of a century later, the New York Times explained that it was the “coup that began Chile’s transformation from a backwater banana republic to the economic star of Latin America.”

On how many Chileans does that star shine? One-fourth of the population lives in absolute poverty and, as Christian Democratic senator Jorge Lavandero has pointed out, the hundred richest Chileans earn more in a year than the entire state budget for social services. U.S. journalist Marc Cooper found quite a few impostors in the paradise of consumption: Chileans who roast in their cars rather than roll down the windows and reveal that they have no air-conditioning, or who talk on toy cellular phones, or who use credit cards to buy potatoes or a pair of pants in twelve monthly installments. Cooper also found several angry workers at the Jumbo supermarket chain. On Saturday mornings, there are people who fill their shopping carts to the brim with the costliest items, then stroll the aisles for a long while, showing off, before abandoning their carts and sneaking out a side door without buying so much as a stick of gum.

Читать дальше