Note to criminals starting out: to murder timidly won’t do. Like business, crime pays, but only when it’s done on a grand scale. The top brass who gave the orders to kill so many people in Latin America are not in jail for murder, even though their service records would make gangsters blush and criminologists go bug-eyed.

We are all equal under the law. Under what law? Divine law? Under earthly law, equality grows less equal every day and everywhere, because power usually sinks its weight onto only one tray on the scales of justice.

OBLIGATORY AMNESIA

Inequality before the law lies at the root of real history, but official history is written by oblivion, not memory. We know all about this in Latin America, where exterminators of Indians and traffickers in slaves have their statues in city plazas, while streets and avenues tend to bear the names of those who stole the land and looted the public purse.

Like the buildings in Mexico City that came tumbling down in the 1985 earthquake, Latin America’s democracies have been robbed of their foundations. Only justice could give them a solid base from which to stand up and start walking; instead, we have obligatory amnesia. As a rule, civilian governments are limited to administering injustice and dashing hopes for change in countries where political democracy keeps crashing into the walls erected by economic and social structures that are democracy’s enemy.

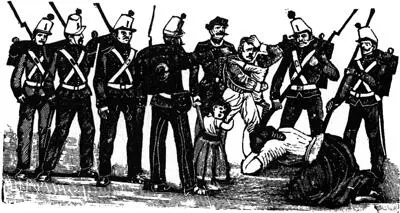

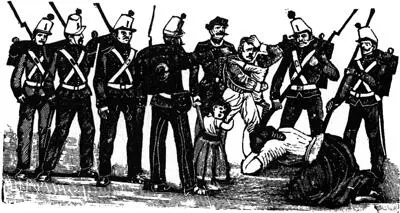

In the sixties and seventies, Latin America’s military leaders took power by assault. To put an end to political corruption, they stole much more than the politicians, an achievement made possible only because they exercised absolute power and started work each day at reveille. Years of blood and dirt and fear: to put an end to the violence of local guerrillas and international red phantoms, the armed forces tortured, raped, or murdered as many people as they could get their hands on, in a vast manhunt that punished every expression of the human desire for justice, no matter how inoffensive.

The Uruguayan dictatorship tortured a lot and killed little. The Argentine one, in contrast, practiced extermination. Despite their differences, the many Latin American dictatorships of those years worked together and were quite similar, as if cut by the same shears. What shears? In the middle of 1998, Vice Admiral Eladio Moll, once chief of intelligence for the Uruguayan military regime, revealed that U.S. advisers had encouraged the regime to eliminate subversives after extracting whatever information it could from them. The vice admiral was arrested — for the crime of candor.

A few months before that, Captain Alfredo Astiz, one of the Argentine dictatorship’s chief slaughterers, was demoted for telling the truth: he declared that the navy had trained him to do what he had done and, in a flight of professional arrogance, added that he was “technically the best prepared in this country to kill a politician or a journalist.” At the time Astiz and other Argentinean officers had been charged or tried in several European countries for the murders of Spanish, Italian, French, and Swedish citizens, but the murders of thousands of Argentines had been pardoned by laws intended to wipe the slate clean.

The Devil Was Hungry

El Familiar is a black dog that breathes fire from his nose and ears. At night his fires roam the cane fields of northern Argentina. El Familiar works for the Devil, giving him rebel flesh to eat, keeping watch on and punishing the peons of sugar. Its victims leave this world without saying good-bye.

In the winter of 1976, under the military dictatorship, the Devil was hungry. On the night of the third Thursday in July, the army entered the Ledesma sugar refinery in Jujuy. The soldiers took away 150 workers. Thirty-three disappeared, never to be seen again.

The laws of impunity also seem cut by the same shears. Latin America’s democracies were resuscitated only to be condemned to paying debts and forgetting crimes. It was as if the new civilian governments were thankful for the efforts of the men in uniform: military terror had created a favorable climate for foreign investment and paved the way for selling off countries at the price of bananas. It was under democracy that national sovereignty was fully abandoned, labor rights were betrayed, and public services were dismantled. All this was done, or rather undone, with relative ease. Accustomed to surviving amid lies and fear, the societies that recovered their civil rights in the eighties were drained of their best energies, as sick from discouragement as they were needy of the creative vitality that democracy promised but couldn’t or didn’t know how to deliver.

For the elected governments, justice meant vengeance and memory meant disorder, so they dribbled holy water on the foreheads of the men who had waged state terrorism. In the name of democratic stability and national reconciliation, they passed laws that deterred justice, interred the past, and preferred amnesia. Several of these went beyond even the most horrific precedents in other parts of the world. In its haste to absolve, Argentina’s government passed a “due obedience” law in 1987 (repealed a decade later when it was no longer needed), exonerating soldiers following orders from any responsibility for what they had done. Since there is no soldier who doesn’t follow orders, whether from the sergeant, the captain, the general, or God, criminal responsibility ended up in heaven. The German military code that Hitler perfected in 1940 to serve his deliria was in fact more cautious: in article 47 it established that a subordinate was responsible for his acts, “if he knew that the superior’s order referred to an action that was a common or military crime.”

The Living Thought of Military Dictatorships

During the leaden years of late, Latin American generals managed to make their ideology heard despite the roar of machine guns, bombs, trumpets, and drums.

Carried away with bellicose exhilaration, Argentine general Ibérico Saint-Jean cried: “We are winning the third world war!”

Carried away with chronological exhilaration, his compatriot General Cristino Nicolaides shouted: “For two thousand years Marxism has threatened Western Christian civilization!”

Carried away with mystical exhilaration, Guatemalan general Efraín Ríos Montt bellowed: “The Holy Spirit runs our intelligence service!”

Carried away with scientific exhilaration, Uruguayan rear admiral Hugo Márquez roared: “We have turned the nation’s history around by three hundred and sixty degrees!”

Celebrating that epic feat and carried away with anatomical exhilaration, Uruguayan politician Adauto Puñales thundered: “Communism is an octopus that has its head in Moscow and its testicles everywhere!”

Читать дальше