So the cousin, her cheek dry now, with just the pink traces of scratches showing, beat out:

“Seg gwasmi yebda useggwas

Wer nezhi yiggwas!”

And she cried out the last two lines in a more piercing voice:

“Meqqwer lhebs iy inyan

Ans’ara el ferreg felli!”

And Malika, the dead girl’s sister, who did not weep but remained standing, motionless, near the doorway, then said in her metallic voice,

“Oh bless you, my uncle’s daughter, come so far to share our grief!”

Then, speaking to the women who had apparently not liked hearing this “mountain” speech, she went on, “For those of you who do not understand the language of our ancestors, this is what my uncle’s daughter has said; this is what she sang for my sister, who is not forgotten.”

Malika stepped out into the middle of the crowd of white veils before she continued, to make sure that her mother, Lla Fatima, was not there. But Lla Fatima still lay unconscious as she had since morning, driven almost mad after spending a long time in trances, carried away by despair. Finally Malika translated for the city-women who only cared to understand in the dialect of the city:

“Since the first day of the year

We have not had one single day of celebration!”

… … … … … … … … … … …

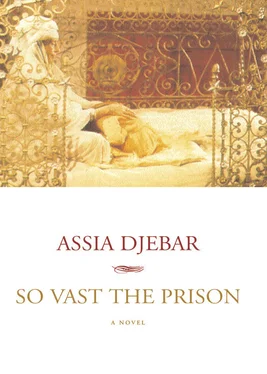

“So vast the prison crushing me

Release, where will you come from?”

At these words, little Bahia, who had stood up, went back to the dead girl and sat down by her head all alone, absolutely determined to stay there, since the men who would carry the funerary board had not yet come …

Bahia, motionless. And even when some kinswoman sprinkled her forehead or her hands with eau de cologne, it was like blessing someone not there. Deep inside, Bahia, mute, face dry, repeated to herself the Berber lament of the cousin who tore her face …

“So vast the prison,” “Meqqwer lhebs.” Two or three words, sometimes in Arabic and sometimes in Berber, were singing inside her, slowly, a sort of rough march, jolting, but also calming — which made it possible for her to watch peacefully as Chérifa, with her face suddenly enwrapped in the swallowing shroud, was carried away.

In the days that followed and then the weeks, then the months and seasons, one after the other, Bahia did not speak. Did not smile. Did not sing.

This is how she lived, cool and calm, but how could they know whether she was in pain or indifferent? Until she was seven.

On the anniversary of Chérifa’s death, or shortly afterward, Lla Fatima agreed to put her youngest child in the hands of a local sorceress. She was told the sorceress knew how to free someone possessed, kidnapped by a beloved now among the dead who held on to this person “despite the will of God.”

It was difficult, but she let her little girl go with an old neighbor, the woman who gave her the advice. “It will be near the beach, in an isolated inlet where the woman lives as a recluse … You will see, with the will and protection of the saints of your lineage, Ahmed or Abdallah and the two Berkanis, father and son, she will succeed!”

Bahia returned that evening silent. The next morning, the last Friday before the month of fasting, just after her mother and big sister completed their prayer, Bahia spoke softly, as if things had always been the way they were now, without sadness: just a few words about the cool breeze and the brightness of the light.

Lla Fatima gave alms every morning for the next week.

Twelve years later Bahia is nineteen. She was eighteen when she had me.

At nineteen, just thirteen months after my birth (because she nursed me only for the first month; she had no more milk after that; she had grown thinner and felt ill. Her lethargy and sadness faded when this blessed pregnancy arrives a few weeks later to renew her energy and make her bloom), she finally has her son. Her first.

So beautiful. A big baby who made her suffer giving birth. But how happy she was afterward hearing the women’s compliments when they came to visit: “White, fat, and so blond, so blond …”

“He has blue eyes, you are lucky, he will be a real lord! A bridegroom! …

“He has his father’s eyes, his lineage is paternal!”

“The women are mountain Berbers,” another whispered, all sweetness.

But Lla Fatima, my mother’s mother, retorted calmly, “It’s true! On our side the men have black eyes and long lashes! They are all dark and handsome at home.” She sighed, thinking nostalgically of her son whom France kept in the Sahara as a soldier, so far away!

The endless talk of the visitors creates a warm babble of sound close by. It is Bahia’s third day after the birth; she will leave her bed before the seventh day for the celebration — what a stroke of luck that after all she delivered her son in the city, and in her mother’s beautiful house, she will enjoy the ritual cermony. A great many women will come as guests; an orchestra of women musicians will provide the music. Lla Fatima attends to it all, as she did when this her youngest child was married (the most beautiful wedding in the city, the one that all the women will talk about for a long time. The bride, after having arrayed herself in the traditional caftan, then was so proudly the first in the city to wear the white gown of European brides: according to the wishes of the bridegroom, the brother’s friend, just out of teachers’ training …).

Consequently Bahia does not worry. As the seventh day unfolds her serenity and contentment will grow in this soothing, new sweetness.

When she bore her daughter a year earlier, it was quite the opposite: Everything had been done hastily and far away, at the first teaching post assigned to the husband, in the mountains north of Bou Saada. As if she had had her first child in exile! On that last day of classes, the baby coming a week too early, whereas they had both expected to leave the next day (in the corners half-open suitcases needed only to be closed). Summer vacation was beginning, her mother had prepared her room for her in the city, the bed, the sheets and the provisions for the celebration with all the women arriving to visit … Now the birth was going to take place in the middle of the mountains! They were going to have to get through it with the midwife, an extremely old peasant woman; she was experienced of course, with a jolly, soothing face, but still, she did not even speak Arabic, except the words to invoke God and to call for patience, just a few expressions from the Koran sprinkled over her chatter. It sounded like some foreign idiom to the woman giving birth as she tried to surmount her pain.

The old woman had wanted to get a rope ready to hang from the ceiling so that the woman in labor could hang on it and help herself by pulling with her arms raised over her head … Bahia refused: She knew that was a peasant custom. No. In the city all they did was tilt the bed … The boiling water was ready, and while the future mother suffered, she recited verses from the Koran … As a last resort they might call the French doctor. Lla Fatima would be determined: he would come, even at midnight, he knew the family … And Bahia, waiting to give birth for the first time, would have been tranquilized. Instead, now, faced with this old peasant woman who came running from the nearby douar , my mother had to suffer, first in silence and then with harsh rattling breaths that became more and more rhythmic — until finally I burst into the light of day.

The old woman set to work with a great laugh. She cut the cord. Turned me quickly upside down. Waited for my first cry. Then she spouted a long sentence that my mother in her weakness heard but did not understand.

Читать дальше