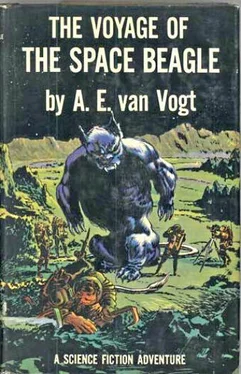

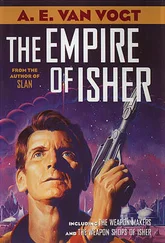

A. E. van Vogt

THE VOYAGE OF THE SPACE BEAGLE

On and on Coeurl prowled. The black, moonless, almost starless night yielded reluctantly before a grim reddish dawn that crept up from his left. It was a vague light that gave no sense of approaching warmth. It slowly revealed a nightmare landscape.

Jagged black rock and a black, lifeless plain took form around him. A pale red sun peered above the grotesque horizon. Fingers of light probed among the shadows. And still there was no sign of the family of id creatures that he had been trailing now for nearly a hundred days.

He stopped finally, chilled by the reality. His great forelegs twitched with a shuddering movement that arched every razor-sharp claw. The thick tentacles that grew from his shoulders undulated tautly. He twisted his great cat head from side to side, while the hair-like tendrils that formed each ear vibrated frantically, testing every vagrant breeze, every throb in the ether.

There was no response. He felt no swift tingling along his intricate nervous system. There was no suggestion anywhere of the presence of the id creatures, his only source of food on this desolate planet. Hopelessly, Coeurl crouched, an enormous catlike figure silhouetted against the dim, reddish sky line, like a distorted etching of a black tiger in a shadow world. What dismayed him was the fact that he had lost touch. He possessed sensory equipment that could normally detect organic id miles away. He recognized that he was no longer normal. His overnight failure to maintain contact indicated a physical breakdown. This was the deadly sickness he had heard about. Seven times in the past century he had found coeurls, too weak to move, their otherwise immortal bodies emaciated and doomed for lack of food. Eagerly, then, he had smashed their unresisting bodies, and taken what little id was still keeping them alive.

Coeurl shivered with excitement, remembering those meals. Then he snarled audibly, a defiant sound that quavered on the air, echoed and re-echoed among the rocks, and shuddered back along his nerves. It was an instinctive expression of his will to live.

And then, abruptly, he stiffened.

High above the distant horizon he saw a tiny glowing spot. It came nearer. It grew rapidly, enormously, into a metal ball. It became a vast, round ship. The great globe, shining like polished silver, hissed by above Coeurl, slowing visibly. It receded over a black line of hills to the right, hovered almost motionless for a second, then sank down out of sight.

Coeurl exploded from his startled immobility. With tigerish speed, he raced down among the rocks. His round, black eyes burned with agonized desire. His ear tendrils, despite their diminished powers, vibrated a message of id in such quantities that his body felt sick with the pangs of his hunger.

The distant sun, pinkish now, was high in the purple and black sky when he crept up behind a mass of rock and gazed from its shadows at the ruins of the city that sprawled below him. The silvery ship, in spite of its size, looked small against the great spread of the deserted, crumbling city. Yet about the ship was leashed aliveness, a dynamic quiescence that, after a moment, made it stand out, dominating the foreground. It rested in a cradle made by its own weight in the rocky, resisting plain which began abruptly at the outskirts of the dead metropolis.

Coeurl gazed at the two-legged beings who had come from inside the ship. They stood in little groups near the bottom of an escalator that had been lowered from a brilliantly lighted opening a hundred feet above the ground. His throat thickened with the immediacy of his need. His brain grew dark with the impulse to charge out and smash these flimsy-looking creatures whose bodies emitted the id vibrations.

Mists of memory stopped that impulse when it was still only electricity surging through his muscles. It was a memory of the distant past of his own race, of machines that could destroy, of energies potent beyond all the powers of his own body. The remembrance poisoned the reservoirs of his strength. He had time to see that the beings wore something over their real bodies, a shimmering transparent material that glittered and flashed in the rays of the sun.

Cunning came, understanding of the presence of these creatures. This, Coeurl reasoned for the first time, was a scientific expedition from another star. Scientists would investigate, and not destroy. Scientists would refrain from killing him if he did not attack. Scientists in their way were fools.

Bold with his hunger, he emerged into the open. He saw the creatures become aware of him. They turned and stared. The three nearest him moved slowly back toward larger groups. One individual, the smallest of his group, detached a dull metal rod from a sheath at his side, and held it casually in one hand.

Coeurl was alarmed by the action, but he loped on. It was too late to turn back.

Elliott Grosvenor remained where he was, well in the rear, near the gangplank. He was becoming accustomed to being in the background. As the only Nexialist aboard the Space Beagle, he had been ignored for months by specialists who did not clearly understand what a Nexialist was, and who cared very little anyway. Grosvenor had plans to rectify that. So far, the opportunity to do so had not occurred.

The communicator in the headpiece of his space suit came abruptly to life. A man laughed softly, and then said. “Personally, I’m taking no chances with anything as large as that.”

As the other spoke, Grosvenor recognized the voice of Gregory Kent, head of the chemistry department. A small man physically, Kent had a big personality. He had numerous friends and supporters aboard the ship, and had already announced his candidacy for the directorship of the expedition in the forthcoming election. Of all the men facing the approaching monster, Kent was the only one who had drawn a weapon. He stood now, fingering the spindly metalite instrument.

Another voice sounded. The tone was deeper and more relaxed. Grosvenor recognized it as belonging to Hal Morton, Director of the expedition. Morton said, “That’s one of the reasons why you’re on this trip, Kent — because you leave very little to chance.”

It was a friendly comment. It ignored the fact that Kent had already set himself up as Morton’s opponent for the directorship. Of course, it could have been designed as a bit of incidental political virtuosity to put over to the more naive listeners the notion that Morton felt no ill will towards his rival. Grosvenor did not doubt that the Director was capable of such subtlety. He had sized up Morton as a shrewd, reasonably honest, and very intelligent man, who handled most situations with automatic skill.

Grosvenor saw that Morton was moving forward, placing himself a little in advance of the others. His strong body bulked the transparent metalite suit. From that position, the Director watched the catlike beast approach them across the black rock plain. The comments of other departmental heads pattered through the communicator into Grosvenor’s ears.

“I’d hate to meet that baby on a dark night in an alley.”

“Don’t be silly. This is obviously an intelligent creature. Probably a member of the ruling race.”

“Its physical developments,” said a voice, which Grosvenor recognized as that of Siedel, the psychologist, “suggest an animal-like adaptation to its environment. On the other hand, its coming to us like this is not the act of an animal but of an intelligent being who is aware of our intelligence. You will notice how stiff its movements are. That denotes caution, and consciousness of our weapons. I’d like to get a good look at the end of those shoulder tentacles. If they taper into handlike appendages or suction cups, we could start assuming that it’s a descendant of the inhabitants of this city.” He paused, then finished, “It would be a great help if we could establish communication with it. Off-hand, though, I’d say that it has degenerated into a primitive state.”

Читать дальше