Ball used the silence that followed as an opportunity to enter the office. He cleared his throat. They were both frozen toward each other like two cats with humped backs. Their jaws were puffed. He could smell the violence. Becky was lighting a cigarette, her hands trembling, and Tremonisha was staring at her, her hands on her hips.

“You’re not to come into this office unless you knock,” Becky said. She was shaking like a wet dog.

“I’m sorry, the receptionist told me to come in.”

“You don’t have to apologize, Ian. This bitch wants to fuck with your play. The same way they did with mine.”

“Look, Tre, nobody was twisting your arm,” Becky said, cuttingly. They were staring at each other. Their chests were heaving. “Nobody begged you, Tre. You didn’t complain as long as the money was coming in. As long as you could take those trips to Europe, to learn and to grow, as you put it. You didn’t complain then.” Tremonisha looked at the floor.

“I was young.”

“Maybe you want to be alone. I can leave,” Ball said.

“Tell him what you want to do with his play. She wants to change your play so that the mob victim is just as guilty as the mob. She wants to drop Cora Mae’s line about their being in the same boat. That’s that collective guilt bullshit that’s part of this jive New York intellectual scene. She wants you to change the whole meaning of the play. She’s saying that the man who reckless eyeballed Cora Mae was just as guilty as the men who murdered him. She feels that Ham Hill’s staring at Cora was tantamount to a violent act. If looks could kill? Huh, Becky? She’s saying that Ham Hill murdered Cora with his eyes.” Tremonisha and Becky were exchanging stares that were so dense he felt that they were probably looking right through each other.

He thought of them in the same households all over the Americas while the men were away on long trips to the international centers of the cotton or sugar markets. The secrets they exchanged in the night when there were no men around, during the Civil War in America when the men were in the battlefield and the women were in the house. Black and white, sisters and half-sisters. Mistresses and wives. There was something going on here that made him, a man, an outsider, a spectator, like someone who’d stumbled into a country where people talked in sign language and he didn’t know the signs. After a long silence Becky said, turning to him: “I just want you to tone it down a little.”

As a climax to this extraordinary scene, Tremonisha started for the door. “Come on, Ian. Buy me a drink. Let’s get out of here. First she cuts the white women out of the lynching scene, and next she wants you to change the whole meaning of the play.” Ball stood there. He thought of a long article he’d read about how plays about women were hot, and that anybody who could put together a halfway decent one could be assured of a performance. And anyway, what did this argument between these women have to do with him? Hadn’t the black ones said that the only thing that had happened since Martin Luther King, Jr., was the black woman, and weren’t the white ones telling themselves that they had come a long way baby? What did a quarrel between these sisters, hugging each other one minute and scratching out each other’s eyes the next have to do with him? “Well, Ball,” Tre finally said. “Are you coming?” He stood his ground. She went to the door and slammed it, but not before giving them both disgusted looks. Ian turned to Becky and said: “Can we talk?” She smiled.

Paul Shoboater, critic for the Downtown Mandarin , kept Ian waiting. He looked at his watch. Paul was forty-five minutes late. He was like that, especially toward up-north fellas. They were from the same neck of the woods, but back home he and Paul didn’t move in the same circles. Shoboater had been in the North as long as Ball had, but refused to drop his down home accent. Shoboater knew that Ball would probably be uncomfortable in this kind of place, with its white and black checkerboard tile floor, and waitresses in black silk dresses and white aprons, and tuxedoed waiters. Ball sat at the bar, sipping from a glass of Pabst Blue Ribbon.

The bartender had sighed when Ball ordered it. Shoboater finally entered, or swept in. He saw Ball, but pretended not to notice him as he greeted some of his friends. Artists and critics from the downtown art scene. He finally reached the spot where Ball was seated, and gave him a cool handshake. The maitre d’ came up bowing and scraping before Shoboater, greeting him as he escorted the pair to Shoboater’s reserved table. Ball followed Shoboater, carrying his Pabst with him and finally placing it on the white linen tablecloth. When the waiter asked them what kind of cocktails they wanted, Shoboater ordered some vintage wine, and Ball ordered another Pabst. The waiter and Shoboater shared a chuckle. The fellas called Shoboater “Eye Spy” because they claimed that his column for the Mandarin was actually a literary reconnaissance mission for tourists who wanted to become acquaintances with the trends and styles of Afro-American culture. An expedition into the heart of darkness, as it were. The fellas claimed that his position made him lazy because his editors didn’t know whether he was faking it or telling the truth. Others said that his real role was that of a hit man for modernism, Pound’s “botched bitch gone in the teeth” reeling from blow after successive blow. The modernists could take Sartre’s late disavowal of existentialism, and the failure of Marxism, or even the death of abstract expressionism, but Freud’s fall, that was the severest blow, and finished off the movement that had been traveling a steady intellectual downhill since the revelations about Stalinism. Freud had achieved the status of a Holy Man for them.

Brashford had claimed that the Jews ran the Downtown Mandarin , and that even though it carried articles that opposed quotas and affirmative action as methods for subsidizing blacks, fifty percent of the revenue of Jewish organizations was derived from government subsidies, and though they had put Shoboater up to claiming that black talent got by because of liberal guilt, the same thing was said about Jewish talent in the fifties; that the rise of the American Jewish novelist coincided with a wave of guilt that swept the country after the discovery of the Holocaust. The fellas also ridiculed Shoboater’s “show-out” ornamental prose style that made his work nearly unreadable — they said that if his prose style were a horse someone would have put it out of its misery long ago.

After a weak toast to Ball’s play, Shoboater skimmed through Ball’s script as though Ball wasn’t even sitting there. Ball could tell that this was the first occasion upon which Shoboater had availed himself of reading the manuscript. When the waiter came up and asked for their orders, Shoboater ordered in impeccable French, which must have impressed the waiter because he had a huge smile while scribbling the order. They both looked at Ball, who said that he would have the same thing as Shoboater.

“So what is this crazy shit of yours that the Lord Mountbatten is doing?” Shoboater said.

“It’s not going to be done at the Mountbatten. They’ve moved it over to the Queen Mother,” Ball said, choking on his pride. Shoboater grinned widely when he heard that.

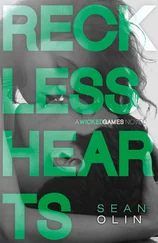

“ Reckless Eyeballing , heh. Nigger, you are crazy, like they say.” Ball wanted to knock his teeth out right there. But thought better of it. He gritted his teeth and in his mind’s eye saw Paul Shoboater falling from the chair and cracking his skull against one of those stone pillars of the restaurant, or the heavy pot that held ferns. He saw the waiter rise from where Paul lay — blood pouring from his head, spattering his three-piece French-cut suit — shaking his head before the shocked fellow diners, and announcing, “He’s dead.”

Читать дальше