How many loaves and fishes are here? But we need not feed this multitude, not loaves and fishes. It is mostly apples. “Pomona, Pomona. Christo Re, Dio Sole.” 33

April 5, Easter Saturday

“But,” he said, “my only real criticism is that this is not my child.”

This is the child but a long time after, drawn into consciousness by Erich Heydt, stabilized, exactly visualized, one summer day on the crowded platform of the Zürich-Stadelhofen station.

The Child was with us when George Plank, Bryher, and I first discussed the “Weekend” and I laughed about Ezra, for the first time in the 12 years of his confinement. I heard his voice, “Goodbye Dave, you’ll come over Christmas Day, won’t you?” There is no reason to accept, to condone, to forgive, to forget what Ezra has done. Sylvia [Beach] made it very clear last night. And here, I should renounce my hope of recalling Ezra, if I dare think of Sylvia’s confinement in a detention camp, her near-starvation, the meager rations shared with her by her friend Adrienne Monnier, during a term of hiding. Dare I go on? There is no reason to hope for his release. “He has books, everything; students come to me in Paris and tell me about him. Fascist . Those dreadful people he knows — that man—.” “Yes,” I said, “I know, news items have been sent me, but.…” “There is a group there. He has everything.…” “I know.” “It was a great mistake, that official prize they gave him.” I said, “But…

I said, “But.” There is no argument, pro or con. You catch fire or you don’t catch fire. “This fruit has a fire within it, / Pomona, Pomona. / No glass is clearer than are the globes of this flame / what sea is clearer than the pomegranate body / holding the flame? / Pomona, Pomona.”

April 7, Easter Monday

So the very day I enter this last note, I hear again from Norman Pearson, “It looks more and more possible that the day of liberation may finally come.” He sends New York Times , April 2 report, and a short article from April 3; London Times is sent me, and Joan found a Jours de France , April 5 notice, “ Ezra Pound, le Mallarme U. S. ne mourra pas chez les fous .” I have among my Easter letters, one too, from Mary de Rachewiltz from Schloss Brunnenburg, Tyrol, “There is some hope of having father with us soon.”

April 9

Mary asked me to visit her when I was at Lugano. There was a local bus, she said, it was not far. But I never went. She sent me photographs of herself and the children. She is looking out of a window of the Schloss or castle, like a girl in a fairy tale, or “Sister Helen,” a poem. She gazes out over the romantic Tyrol landscape, far, far. I hardly dare think of her and a copy of an early portrait that Ezra had sent me, with her hair, wheat-gold, flowing down over her shoulders. There is Sigifredo too, reaching up to a sort of della Scala knocker on a great door, with fair hair in a halo. Mary again asks me to visit them, “especially now as there is some hope of having father with us soon.”

I wait for letters with the intense apprehension with which I waited almost 50 years ago, when Ezra left finally for Europe. Through the years, I have imposed or superimposed this apprehension on other people, other letters. A sort of rigor mortis drove me onward. No, my poetry was not dead but it was built on or around the crater of an extinct volcano. Not rigor mortis . No, No! The vines grow more abundantly on those volcanic slopes. Ezra would have destroyed me and the center they call “Air and Crystal” of my poetry.

Now, I am in a fever of apprehension and excitement. I was separated from my friends, my family, even from America, by Ezra. I did not analyse this. When Frances came into my life, I could talk about it — but even so, only superficially. But I read her some of the poems that Ezra and I had loved together, chiefly Swinburne. “You read so beautifully,” said Frances. I read Andrew Lang’s translation of Theocritus that Ezra had brought me. I wrote a poem to Frances in a Bion and Moschus mood.

O hyacinth of the swamp lands,

Blue lily of the marshes,

How could I know,

Being but a foolish shepherd,

That you would laugh at me?

April 10

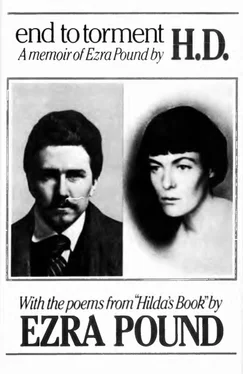

Father . In the new Eva Hesse Arche Verlag 34edition of selections of Ezra’s prose, there is a photograph of Ezra as he left the Pisan camp, fettered, between two detectives. There are the 1946–1948 pictures which are familiar from the book jackets, and the 1955 one in the deck chair in the garden at St. Elizabeth’s. There is the earliest photograph, taken, they state here (and in the little booklet 35that Mary sent me, published by Pesce d’Oro, Milan, for the 70th birthday) in Venice, at the time of the publication of his first book, A Lume Spento , 1908. I am sure that this picture is much earlier. The atmosphere is not Venetian — nor the chair. This is a younger Ezra even than the one I met first when I was 15.

April 11

He shakes his tawny head (wheat-colored, I have written, and Ezra has written, “a sheaf of hair / Thick like a wheat swathe”), gone grey now, they say, and the Ameisen , he seated on the grass, clutch eagerly for the scattered grains. Some fell by the wayside. Bushel baskets of inseminating beauty fell upon barren ground. There is much chaff among the wheat. Who can sort out the contents of the controversial Cantos?

April 12

Norman Pearson can sort them out. He writes me, “They are an ambitious poem and a great poem, and the problems he presents (even when I don’t agree with the solutions) are the problems of our age.”

I spoke of provincial colleges having had a curious insemination. But years ago, the older foundations accepted Ezra Pound. We know of his staunch supporters, Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot, Auden, Hemingway, and we have the names of that gallant band that awarded him the rabidly contested or controverted Bollingen Prize in 1949, for the Pisan Cantos . But my contact is with Pearson and that poignant appeal, “Tell Pearson I can’t go it alone.”

April 13

Pearson mentions this in one of his last letters, as “his agonized appeal.” Joan finds me a notice from Le Figaro Littéraire , April 12, Ezra Pound “ressuscité”? It seems that a great deal will be resurrected or re-born once Ezra is free. Consciously or unconsciously, it seems that we have been bound with him, bound up with him and his fate.

April 14

Waiting — what news, what letters, what press cuttings? I don’t suppose that I really wanted to keep his letters. There was a great untidy bundle of them, many of them written on notepaper he had appropriated from hotels, on a sort of grand tour a wealthy aunt or old family friend had taken him. There was a group photograph, tourists in costume, a young Ezra in a fez. Was that among the papers? It was as if he wrote me from those fabulous romantic places, Carcassonne, Mount St. Michael. I see the illustrations on the letter heads. The writing did not change appreciably, it scrawled as always, or was comparatively neatly spaced, as in the autografo of the reproduced “Venetian Night Litany” 36in the Piccola Antologia that Mary sent me. I did not ask about the letters when I met my parents in Genoa, autumn 1912—was it? But my mother took me aside, “I think you will be relieved to know that your father burnt the old letters.…”

Erich was very shocked. Perhaps I was too, but that shock, as with the other Poundiana, lay dormant.

Erich liked my fertility symbol, as he called it, the head, the tawny wheat-colored hair (now gone grey), scattering grains or seeds for the eager Ameisen , clustered on the grass or crowded in the dim, uncanny hall of St. Elizabeth’s. We wait with apprehension but with a new sort of peace. This is what supremely matters. Sheath upon sheath of self seems peeled away. I begin to understand this “strange man” as the London Times of April 9 called him, in a sympathetic special article. I was not equipped to understand the young poet.

Читать дальше