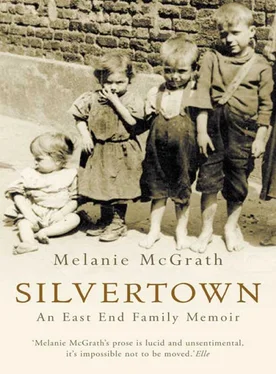

SILVERTOWN

An East End Family Memoir

Melanie McGrath

In memory of my grandparents,

Jenny Fulcher and Leonard Stanley Page

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part Two

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Out of the strong came forth sweetness

Judges 14 and motto of Lyle’s Golden Syrup

You could say that Jenny Fulcher led a very ordinary life. She grew up, worked, married and had children. Her life was subject to the usual disquiets and worries. She fretted over her debts. She worried for the future. Every so often, lying in bed in the flat dawn light, she would wonder what the point of all the struggle was. And then she would get up and make a pot of tea and get on with it. Sometimes a voice in her head whispered that she was a bad wife and a poor mother. Other times the voice soothed and said she had done her best. From time to time, she wondered if anyone had ever really loved her. A few small comforts kept her going: tinned red salmon, cheap perfume and the scandal stories in Reveille magazine. She loved TV soaps and flowers – freesias and violets in particular. She knitted and sewed patchwork and converted the results into tea cosies. Over the nine decades of her life she made enough tea cosies to cover all the teapots of England.

It was the kind of life that could have belonged to a thousand women living in the mid years of the twentieth century in the East End of London. Except that it didn’t. It belonged to Jenny.

Jenny’s turn in the world began in 1903 in Poplar. The death of Queen Victoria two years earlier had ended an era, but remnants of the old century persisted. Women still wore corsets and horses still pulled hackney carriages. The streets still mostly unlit and as slippery as a snake pit. The East End had a grim reputation, and for the most part it was deserved. In the same year Jenny was born, Jack London visited the place and wrote a book about what he saw. He called it People of the Abyss .

My grandmother Jenny grew up in that Abyss. To be an East Ender then was to be among the lowest of London’s poor, but Jenny never thought of herself as low. To Jenny, there was only respectable and common and by her own account she was respectable. This had nothing to do with money – no one in the East End had much of that; it had to do with blood and conduct.

Jenny was salty and wilful, as thin and prickly as the reeds that once grew where she was born. Her heart was full of tiny thorns, which chafed but were never big enough to make her bleed. Vague feelings drifted about her like mist: bitterness, resentment and rage, mostly. Life was as much a mystery to her as she was to herself. She’d spend hours plotting how to squeeze an extra rasher from the butcher, but on the bigger issues she was helpless. She grasped the details without understanding anything of the general rules. She never had the means to manage her life and so was destined to be bent in the shape of desires, urges and ambitions greater than her own.

All the same, when her face lit up it was like a door swinging out into sunshine. There was something irrepressibly naughty about her. You’d imagine her standing behind your back poking her tongue out at you. She revelled in playing the martyr but was comically bad at the part. She’d insist on giving you the last piece of cake, then reach into her handbag when she thought you weren’t looking, pull out a huge bar of chocolate, stuff it in her mouth all at once and pretend she had a cough and couldn’t talk. Her luxuriant moaning had to be witnessed to be believed. On bad days everything from her kidneys to her knitting cost too much, ached like geronimo or was doing its best to rip her off.

No life is without its joys, though, and Jenny Fulcher harboured two great passions. The first of these was the crystallised juice of an Indian grass, Saccharum officinarum L. , otherwise known as sugar. She favoured the bleached, processed, silvery white stuff, in crystal form or cubes. She spooned it into her tea in extravagant quantities and whenever she thought no one was looking, she’d lick a bony finger, dunk it in the sugar bowl and jam it into her mouth. She was partial to biscuits, cakes, marmalade, tarts and chocolate too, but sweets were really her thing. Over the course of her life, thousands of pounds of Army and Navy tablets, barley sugars, candyfloss, Everton mints, Fox’s glacier mints, humbugs, iced gems, jellies, liquorice comfits, Mintoes, nut brittle, orange cremes, pralines, Quality Street, rhubarb and custards, sugared almonds, Toblerone and York’s fruit pastilles, met their sticky end on my grandmother’s sweet tooth. Sugar was both lover and friend. It had the capacity to seduce, and also to keep her company. Her life went sour so quickly she relied on sugar to lend it sweetness. Sugar was the only thing she had the courage to make a grab for. Even after her hearing went she was never quite deaf to the rustling of humbug wrappers. When her sight failed she could still spot a Fry’s Chocolate Crème bar lying on a table top.

Though she didn’t realise it, my grandmother’s other great love was the East End. She moaned about it constantly – the cramped streets with their potholed pavements, the filthy kids and the belching factories – but she hated the thought of leaving, even for a day. She rarely ventured west and seldom troubled herself with whatever lay on the other side of the Thames. Her list of disgruntlements was long but she never really hankered to be anywhere else. The East End was a mother to her, and she had no means to imagine herself without it. She gave up her health for sugar but she gave up everything else for the East End.

Jenny Fulcher had a husband, my grandfather Leonard. He was not one of her passions. On the surface, they didn’t even have much in common. She was the product of the low-lying lanes and turnings of Poplar, where the Thames coils into a teardrop. He came from the sodden terrain of mud and reeds further to the east, from a hamlet sprinkled over the flat fields and rush beds of southern Essex. He was the son of a farm labourer, she the daughter of a journeyman carpenter. She grew up among the factories and tenements sandwiched between the Thames and the West India Docks. He passed his childhood among clouds and a sweep of cabbage fields.

All the same, they shared something beyond the everyday. There was something of the east of England about them both. Their beginnings were bogged down in poverty, their prospects tarnished and their horizons low. They began life on the flat. For years they both looked up at the world, and the world, in its turn, looked down on them.

On the surface, Len Page was all charm and muscular wit. Anyone who didn’t care to look too hard would see a diamond bloke, smartly kitted out, with a military swing to his step. People said he was a bit of a laugh. A right old type. In fact he was several types at once. The guv’nor, the back-slapper, the all-round card, but also the trickster, the slippery fish, the spiv. To tell the truth, Len Page was whatever type would get him where he wanted to go. He was as ambitious as the weeds that push up through concrete. To watch him closely was to watch the hatching and execution of unspoken plans.

Читать дальше