Len also had two passions: the country and a woman called June. But there will be time for them later.

PART ONE

Poplar was built on the back of the sea trade. About six hundred years ago, the place was marked by a single tree standing on lonely marshes and pointing the ancient route from London to Essex. The loops of the Thames at Limehouse Reach in the west and Blackwall Reach in the east protected the area from the worst of the river floods, and in 1512 the East India Company took advantage of its sheltered position to establish a ship-building business at the eastern edge. Very soon after, houses went up on the sloppy soil, craftsmen moved in, then shopkeepers. Oakum merchants arrived, followed by gluemakers, ironmongers, outfitters, manufacturers of naphtha, turpentine, creosote, varnish, linen, tar, timber boards, linseed oil and rubber goods, and Poplar became a town of ropemakers and sailmakers, chandlers, cauterers, uniform-makers, seamen, carpenters, ships’ engineers and, of course, ships.

Poplar was once a place that counted. It was from Brunswick Wharf on its eastern edge that the Virginia Settlers sailed. In 1802 the East India Company, frustrated by the small size of the upstream docks and wharves in the London Pool beside the Tower, carved out two spectacular corridors of impounded water, the East and West India Docks, one on each side of the mouth of the Isle of Dogs. Two-masted tea clippers, brigantines, colliers, packet boats, screw steamers, schooners, riggers, cutters, whalers, wool clippers, shallops, four-masters, dromonds, barges and lighters moored at the quays and wooden dolphins of these broad new docks, half-sunk with barrels of molasses, boxes of bananas, silk, pineapples, parrots, spices, tea, rice, sugar, grain, coffee, cocoa mass, ballast, monkeys, macaws, ivory, alabaster, basalt and asbestos, and discharged their cargoes safely into the warehouses inside the dock walls. It was a great time for trade and the East and West India Docks grew so fast that the bigger ships, the tea clippers and steamers, often found themselves moored for as long as a month at mid-stream anchor, waiting their turn to discharge.

My grandmother’s ancestors were tidal people, Huguenots who were washed first into the East End then into Poplar during the persecution of Protestants by Catholics in France in the 1680s. Afraid for their lives, they sailed up the Thames and found sanctuary in East London. Many gathered in Spitalfields near the City walls; others fanned out among the numerous little villages along the river, hoping to lie low for a while then move back to France once the troubles were done. But over the years of their exile their number multiplied and they stayed. Fuelled by the frantic energy of immigrants with something to prove, they evolved quite naturally into entrepreneurs, working as ragmen, clothiers, silk spinners and dyes-men. At Spitalfields they built silk weaveries and found a way to fix scarlet dye into silk which they then sold back to Catholic cardinals for robes. For more than a hundred years the River Lea ran red with their labours.

They developed English habits and their names gradually Anglicised, but after three hundred years you could still spot an East Ender with Huguenot blood. Take Jenny Fulcher. She was tiny, sallow, with the horse-brown hair of southern women. Her skin would only have to see the sun to turn brick brown. It was an embarrassment to her family. Fer gawd’s sake git some powder on yer face, you’re as black as a woggie-wog, her mother, Sarah, would say whenever the summer came. Having no money for powder, Jenny would salt her skin with bicarb of soda, because there was nothing worse than looking foreign (except being foreign, which was unthinkable).

Poplar is a mess these days. It has lost its civic quality and become little more than a scattering of remnants and cheap offcuts sliced through by the rush of the East India Dock Road and the Northern Approach to the Blackwall Tunnel. The workhouse has gone, and the East India Dock, but if you look carefully, what remains tells a story about how Poplar used to be. At the bottom of Chrisp Street, where a very fine market once stood, the monolithic pile of the Poplar Baths still stands, though the building is derelict and surrounded by razor wire. Along the High Street, between the new-build housing developments and shabby Sixties shopping parades, there remain the architectural remnants of Poplar’s marine and trading past: a customs house, some ancient paintwork advertising a chandlery, an old seamen’s mission. Further east on the Tunnel Approach, the magnificent colonnades of Poplar Library gather dirt from the traffic and its boarded up windows furnish irresistible spaces for taggers and graffiti artists.

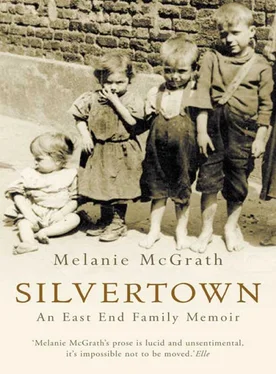

By the time Jenny (or Jane, as she was then) is born, Poplar has become filthy and overcrowded, a victim of its own success. Those who can afford it have moved out to more spacious environs further from the dock walls. My great grandfather, John Fulcher, or Frenchie as he was known, his wife, Sarah, and their children live in Ullin Street, between the Cut and the River Lea. Ullin Street is near to Frenchie’s place of work, the Thames Ironworks at Orchard Place. Poplar is jammed with terraces of shabby lets and subdivisions put up by speculators as housing for dockworkers. There are a hundred, even a thousand similar streets stacked along the eastern flank of the city like so much left luggage. They are ugly, redoubtable places, but by no means the worst the East End has to offer.

If you are born there, the docks are the language you speak, the smells you know, the ebb and flow of your life. And so it is with Jane. She grows up beside queues of drays, moving slowly towards the dock gates; beside the twice-daily rush of men struggling to find day work; beside the crush of seamen and foreigners, their strange languages breaking from beneath turbans, yellow faces, pigtails, ice-blue eyes. Jane is aware of the tidal pull of the water before she can even read the tide tables flyposted on the sides of every public house in Poplar. The phalanxes of Port of London Authority policemen, the pawn shops, the bold glances of loose women, the rat nests and dog fights, the boozed-up sailors of a Saturday night, the bustling tradesmen, the drinking dives and gambling holes, the deals made, the greetings and the farewells, the dockers’ pubs and pawnbrokers and seamen’s missions: all these are familiar to her.

In 1903 the Fulcher family are living in the upper two rooms at number 4 Ullin Street. At the southern end of the street sits the bulking, red brick mass of St Michael and All Angels church and beside it, a gloomy vicarage set in a dark little garden. The remainder of the street is lined with poky terraces where it is common for families of seven or eight to be packed into a single room. There are men in Ullin Street who are forced to work night shifts because there is nowhere for them to sleep until their children have gone to school and the beds are free. And not unskilled labourers either, but craftsmen and artisans. The 1891 census shows sailmakers, foundrymen, glass blowers and carpenters, all living on Ullin Street.

Having two rooms between them, the Fulchers are among the more fortunate. The larger of these rooms is an imperfect square of about twelve feet containing an iron bedstead with an ancient horsehair mattress where Frenchie, Sarah and the younger children sleep, a large fireplace in which a coal stove burns whenever there is money for coal, a gas lamp, a table fashioned by Frenchie from fruit crates, a decaying wicker chair and two fruit crate stools. The room is for the most part mildewy and cheerless, smelling of the family’s activities: cooking, bathing, smoking and sex. It is rarely warm enough to open the window and the wooden sashes have in any case swollen with damp and stuck in their frames, though the draught still sails into the room like an unwanted relative. During the autumn and winter Sarah has to lay newspaper over the panes to keep the cold out, and for six months of the year the family live more or less in darkness, the gas lamp on the wall having been deemed an extravagance they can do without.

Читать дальше