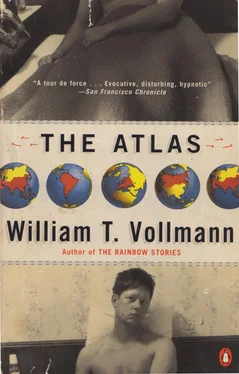

William Vollmann - The Atlas

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Vollmann - The Atlas» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, ISBN: 1996, Издательство: Viking, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Atlas

- Автор:

- Издательство:Viking

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:9780670865789

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Atlas: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Atlas»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Atlas — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Atlas», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And now I did not have to think about the mosquitoes too much, either because I was in my tent again looking at the bloodstains on the ceiling where I'd squashed the ones that had followed me in and bitten me and gotten away for a minute or two before I caught up with them, and I could see the shadows of so many others on the outside of the nylon, smelling the blood inside me but unable to get at me, waiting for me to go out, and then after I ran back inside scratching my new bites and killing the assault guard, the others would land on the fly again, waiting now for the sunny night to end so that I'd expose my flesh to another day; but meanwhile I was inside and they could not torture me; I did not have to slap the backs of my thighs every minute on general principles, or sweep my sleeve across my face to kill mosquito-crowds; and it was astounding how quickly I forgot them. They were all around me and had not forgotten about me, but I'd shut them out and they meant nothing. I cannot remember what I thought about. Most likely I did not have to think about anything, because I'd gained asylum into an embassy of the easy world that I was used to, enjoying it flapping round me in the sunlight like a boat, all blue and orange, with the shadow of the blowing fly bobbing up and down.

When I hitchhiked from San Francisco to Fairbanks, mosquitoes surrounded me with the hymning hum of a graduation — not right away, of course; not until I got to Canada. As soon as I was safely in a vehicle they could not affect me anymore and I rode the familiar thrill of speed and distance, lolling in the back of the truck, with a beautiful husky kissing my hands and cheeks, and we slowed to let a moose get out of the road and at once I heard them again. — A mosquito bit me. — I was on the Al-Can Highway now. I forgot the night I'd given up, not yet even in Oregon, and stayed at a motel, my face redburned and filthy, my eyes aching; and it had felt sinful to spend the sixteen dollars on the room but it was raining hard as it had been all day, so no one would pick me up. In hitchhiking as in so many other departments, the surest way not to get something is to need it. The more the world dirtied me, the less likely someone would be to take me in. — But the next morning was sunny and I had showered and shaved, which was why a van picked me up within half an hour and took me into Oregon, and as I rode so happily believing that I now progressed, I didn't even consider that the inside of the van was not so different from the inside of the motel; I was protected again. When I remember that summer, which now lies so far behind me, I must own myself still protected, in a fluctuating kind of way, and so a question hovers and bites me unencouraged: Which is worse, to be too often protected, and thereby forget the sufferings of others, or to suffer them oneself? There is, perhaps, a middle course: to be out in the world enough to be toughened, but to have a shelter sufficient to stave off callousness and wretchedness. Of course it might also be said that there is something depressing and even debasing about moderation — how telling that one synonym for average is mean!

On the long stretch of road between Fort St. John and Fort Nelson, where the mosquitoes were thickest, we came to where the Indian woman was dancing. It was almost dusk, round about maybe nine or ten-o'-clock. The country was full of rainbows, haze and yellow flowers. Every hour or so we had to stop to clean the windshield because so many mosquitoes had squished against it, playing connect-the-dots with the outlines of all things. We pulled over and went to work with ammonia and paper towels. They found us as soon as we got out. The driver's head was a big black sphere of mosquitoes. There wereidozens of them in the space between my glasses and my eyes. When we got back into the camper, mosquitoes spilled in through the open windows. We jittered along at fifty miles an hour over the dirt road until the breeze of our passage had sucked them out. By then the windshield was already turning whitish-brown again from squashed mosquitoes. The driver did not want to stop again just yet, but I noticed that he was straining his eyes to see through the dead bugs, and I was just about to say that I didn't mind cleaning the windshield by myself this time (I was, after all, getting a free ride), when far ahead on that empty road (we hadn't met another vehicle for two hours) we saw her capering as if she were so happy, and then we began to get closer to her and saw the frantic despair in her leapings and writhings like some half-crushed thing's that could not die. Not long ago I thoughtlessly poured out a few drops of dilute solvent upon waste ground, and an earthworm erupted, stretched toward me accusingly, stiffened and died. But the convulsions of this woman went on and on. Just as her dance of supposed happiness had seemed to me entirely self-complete like masturbation, so this dance of torture struck me as long-gone mad, sealing her off from other human beings, as if she were some alcoholic mumbler who sheds incomprehensible tears. It was not until we were almost past that I understood behind our hermetic windows that she was screaming for help. I cannot tell you how terrifying her cries were in that wild place. The driver hesitated. He was a good soul, but he already had one hitchhiker. Did he have to save the world? Besides, she might be crazy or dangerous. Her yellings were fading and she was becoming trivial in the rearview mirror when he slowed to think about it, and it was only then that we both understood what we had seen, because protected brains work slowly: mosquitoes darkened her face like a cluster of blackberries, and her legs were black and bloody where the red shorts ended. The driver stopped. Mosquitoes began to pelt against the windows.

We had to help her get in. She embraced us with all her remaining strength, weeping like a little child. Her fearfully swollen face burned to my touch. She'd been bitten so much around the eyes that she could barely see. Her long black hair was smeared with blood and dead mosquitoes. Her cheeks had puffed up like tennis balls. She had bitten her lip very deeply, and blood ran down from it to her chin where a single mosquito still feasted. I crushed it.

That afternoon, no doubt, she'd been prettier, with sharp cheekbones that caught the light, a smooth dark oval face, dark lips still glistening and whole, black eyes whose mercurial glitter illuminated the world yet a little longer, shiny black hair waved slantwise across her forehead. That was why the man in Fort Nelson had decided to support her trade. Reservation bait, he thought. She got in his truck, and there were some other men, too; they used her services liberally.

But unlike slow mosquitoes, who pay the bill, if only with their lives, the men had their taste of flesh with impunity. They weren't entirely vile. They didn't beat her. They only left her to the mosquitoes. They let her put her clothes back on before they threw her out—

She'd tried to dig a hole in the gravelly earth, a grave to hide in, but she hadn't gone an inch before her fingers started bleeding and the mosquitoes had crawled inside her ears so that she couldn't think anymore, and she started running down the empty road; she ran until she had to stop, and then the mosquitoes descended like dark snow onto her eyelids. Two can had passed her. She'd craved to kill herself, but the mosquitoes would not even give her sufficient peace to do that. I'll never forget how I felt when she squeezed me in her desperate arms — I'll never forget her dance.

That was the most horrible thing that I have ever seen. For awhile I thought about it every day. 1 know I thought about it when at the end of that summer I was hitchhiking home and had gotten as far as Oregon, where I slept entented in a tree-screened dimple on a field by a white house, hoping that no one in the white house would see and hurt me, and the next morning I ducked under the fence and was back on the shoulder of the freeway and it was already a very hot morning, so I was drinking from my canteen (which I'd filled at a gas station in Portland) when another hitchhiker came thumping down the road toward me. He was like a prophet from the old times. He wore a long robe and carried a great wooden staff which he slammed down at every step. He was not so old, and yet his beard was long and gray (possibly from dust), and his gray hair fell to his shoulders and his eyes were wild like a bull's. His face was caked with dust. He licked his lips as he came near me, and his eyes were on me unwaveringly, so I offered him water as he came closer and closer, continuing to stare into my eyes, and then he shook his head sternly and walked on. I did not live up to his ideals. There was another hitcher I'd met in Washington State who'd been crazy and called himself the Angel Michael and whispered to me that he didn't know anymore whether he was a boy or a girl and I believed him because he was so angelic: angels are undoubtedly hermaphrodites. In the same way, I believed in the prophet wholly. I could not but admire him for rejecting me. He went on and on down the freeway shoulder, with barbed wire at his right shoulder and can at his left, growing smaller (though I could still distinctly hear the tapping of his stick) and I wondered what he would have done or said if it had been he and only he who came across the woman whom the mosquitoes were eating. I could almost see him there on the Al-Can, toiling on, mile after mile, his face black-veiled like that minister in Hawthorne's tale, black-veiled with mosquitoes; he'd walk on and stab the gravel with his staff and never deign to brush away a single mosquito; he'd glare terribly through eyes swollen almost shut by mosquito bites and go on, mile after mile, week after week; and maybe someday he'd come upon that woman shrieking in her crazed torment. Would he have stopped then; would the mosquitoes leave her for him in a single flicker of his divinity, after which he'd pass on in silence, followed by unimaginable clouds of humming blackness? Would she fall to her knees then and thank God and regain herself? — Or would he never have stopped at all, marching contemptuously on, ignoring her need as he ignored my gift, and dwindled just the same along that highway's inhuman straightness?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Atlas»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Atlas» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Atlas» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.