I understood this intention quite clearly as I wrote, but looking back now I see, also, a very young writer finding a form to contain all his various selves. I was moving between cultures, from India to America and back. I was a wanderer between nation states, I negotiated my way through their rigid borders and bureaucracies, and what could be more modern than that? I was surely a postmodern lover of modernist fiction. Yet, in my creative urges, in the deepest parts of myself, I also remained somehow stubbornly premodern. I didn’t use those premodern forms only for political and polemical reasons; I wasn’t only trying to ironize psychological “realism” by placing it next to the epic and the mythical, or only to create lo real maravilloso as a critique of bourgeois Western imperial notions of the real. No, the impulse was not merely negative. This multiply layered narrative was how I lived within myself, how I knew myself, how I spoke to myself. There was the modern me, and also certain other simultaneous selves who lived on alongside. These “shadow selves”—to follow sociologist Ashis Nandy — responded passionately and instantly to epic tropes, whether in the Mahabharata or in Hindi films; believed implicitly and stubbornly in reincarnation despite a devotion to Enlightenment positivism; insisted on regarding matter and consciousness as one; and experienced the world and oneself as the habitations of devatas , “deities” who simultaneously represent inner realities and cosmic principles. So my book — to speak in my voice — had to contain these selves too.

This un-modern half of my book tended to confuse my American writing-program peers. In our workshops, the prevailing aesthetic tended toward minimalism; the models were Raymond Carver and Ann Beattie and Bobbie Ann Mason. The winding tales I brought in were judged, at least initially, to be melodramatic, mystical, exotic, strange. I didn’t try to explain what I was trying to do mainly because I didn’t have a vocabulary in which I could articulate the lived sensation of this shadow-world within me. I wrote on.

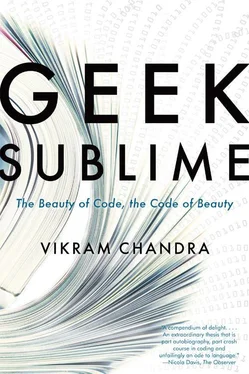

My other life as a computer geek was excitingly active and remunerative. As I taught myself about code, I discovered yet another culture on the newsgroups of Usenet and in meetings of the Houston Area League of PC Users (HAL-PC), “the world’s largest PC user group.” Programmers had their own lingo, their own hierarchies of value and respect, their own mythology. Many of these new norms were being created online. By the turn of the twenty-first century, Scott Rosenberg notes, programmers were writing

personally, intently, and voluminously, pouring out their inspirations and frustrations, their insights and tips and fears and dreams, on Web sites and in blogs. It is a process that began in the earliest days of the Internet, on mailing lists and in newsgroup postings … Not all of this writing is consequential, and not all programmers read it. Yet it is changing the field — creating, if not a canon of the great works of software, at least an informal literature around the day-today practice of programming. The Web itself has become a distributed version of that vending-machine-lined common room … an informal and essential place for coders to share their knowledge and kibitz. It is also an open forum in which they continue to ponder, debate, and redefine the nature of the work they do. 1

One of the urtexts in this shared folklore of computing is “The Story of Mel, a Real Programmer.” It first appeared on a Usenet discussion board in May 1983, as a riposte to a recently published article “devoted to the *macho *side of programming [which] made the bald and unvarnished statement: Real Programmers write in FORTRAN.” 2Our Usenet storyteller here, like any chronicler of the days of yore, wants to set the quiche-eating, FORTRAN-writing young ’uns straight. He begins:

Maybe [real programmers] do [use FORTRAN] now, in this decadent era of Lite beer, hand calculators, and “user-friendly” software but back in the Good Old Days, when the term “software” sounded funny and Real Computers were made out of drums and vacuum tubes, Real Programmers wrote in machine code. Not FORTRAN. Not RATFOR. Not, even, assembly language. Machine Code. Raw, unadorned, inscrutable hexadecimal numbers. Directly. 3

This post was originally written in straightforward prose by Ed Nather, an astronomer, but some anonymous coder responded to its rhythms and elegiac tone and converted it into free verse, and so it has existed on the Web ever since:

Lest a whole new generation of programmers

grow up in ignorance of this glorious past,

I feel duty-bound to describe,

as best I can through the generation gap,

how a Real Programmer wrote code.

I’ll call him Mel,

because that was his name. 4

Mel, the eponymous protagonist of this epic, is the kind of programmer who is already a rarity in 1983: he understands the machine so well that he can program in machine code. The conveniences afforded by high-level languages like FORTRAN and its successors — which now all seem primitive — have by 1983 already so cushioned the practitioners of computing from the metal, from the mechanics of what they do, that they are hard-pressed to debug Mel’s code. Mel’s understanding of his hardware seems uncanny, mystical, a remnant from a bygone heroic epoch:

Mel never wrote time-delay loops, either,

even when the balky Flexowriter

required a delay between output characters to work right.

He just located instructions on the drum

so each successive one was just *past *the read head

when it was needed;

the drum had to execute another complete revolution

to find the next instruction.

He coined an unforgettable term for this procedure.

Although “optimum” is an absolute term,

like “unique,” it became common verbal practice

to make it relative:

“not quite optimum” or “less optimum”

or “not very optimum.”

Mel called the maximum time-delay locations

the “most pessimum.”

…

I have often felt that programming is an art form,

whose real value can only be appreciated

by another versed in the same arcane art;

there are lovely gems and brilliant coups

hidden from human view and admiration, sometimes forever,

by the very nature of the process.

You can learn a lot about an individual

just by reading through his code,

even in hexadecimal.

Mel was, I think, an unsung genius. 5

Within the division of Microsoft that produces programming tools, a Mel-like programmer is represented by the persona “Einstein,” who is an “expert on both low level bit-twiddling and high-level object oriented architectures.” 6There is also another persona named “Elvis,” a “professional application developer.” 7As described by Eric Lippert, former senior software engineer at Microsoft, both Einstein and Elvis “got their jobs by studying computer science and going into development as a career.” 8And then there is the persona “Mort,” who is “an expert on frobnicating [tweaking, adjusting] widgets, [who] one day realizes that his widget-tracking spreadsheets could benefit from a little [Visual Basic for Applications] magic, so he picks up enough VBA to get by.” 9

The vast majority of programmers in the world today are Morts. Despite my intermittent, fumbling attempts at studying data structures and algorithms — the bricks and mortar of computer science — I most definitely remain on the Mort end of the scale. The ever-receding minority of Mels and Einsteins has observed this democratization of the computer with mixed feelings: on the one hand, the legendary early hackers at MIT and Apple are revered precisely because they took on the bureaucratic priesthood that protected the mainframes, defeated its defenses, and made computing available to all; on the other, the millions of Morts who have benefited from the computer revolution produce awful, bloated, buggy software because they don’t know how the machine really works, and, what’s worse, most Morts don’t want to know. “Mort is a very local programmer — he wants to make a few changes to one subroutine and be done,” writes Lippert.

Читать дальше