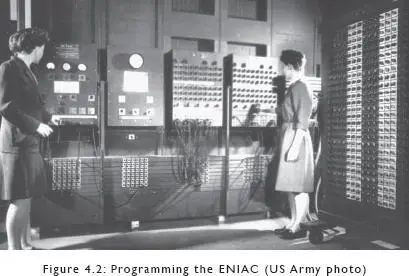

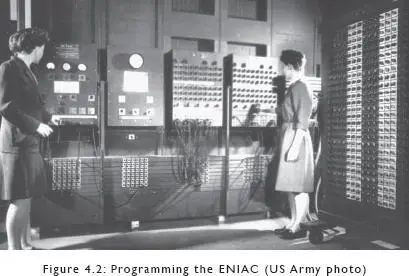

But to my astonishment, [Dr von Neumann] never mentioned a stop instruction. So I did coyly say, “Don’t we need a stop instruction in this machine?” He said, “No we don’t need a stop instruction. We have all these empty sockets here that just let it go to bed.” And I went back home and I was really alarmed. After all, we had debugged the machine day and night for months just trying to get jobs on it.

So the next week when I came up with some alterations in the code, I approached him again with the same question. He gave me the same answer. Well I really got red in the face. I was so excited and I really wanted to tell him off. And I said, “But Dr. von Neumann, we are programmers and we sometimes make mistakes.” He nodded his head and the stop order went in. 19

Once von Neumann and everyone else involved with computers understood this hitherto unimaginable fact — that programming, translating algorithms into the language of machines, was very difficult — programmers became valuable commodities. A 1959 Price Waterhouse report warned that “high quality individuals are the key to top grade programming. Why? Purely and simply because much of the work involved is exacting and difficult enough to require real intellectual ability and above average personal characteristics.” 20Such individuals weren’t easy to find, and as corporations looked for competitive advantage by computerizing their business processes, a shortage resulted. Corporations set up training programmes, fly-by-night vocational schools sprang up guaranteeing jobs: “There’s room for everyone. The industry needs people. You’ve got what it takes.” 21

In 1967, Cosmopolitan magazine carried an article titled “The Computer Girls” that emphasized that programming was a field in which there was “no sex discrimination in hiring”—“every company that makes or uses computers hires women to program them … If a girl is qualified, she’s got the job.” Admiral Grace Hopper, programming pioneer, assured the Cosmo readers that programming was “just like planning a dinner … You have to plan ahead and schedule everything so it’s ready when you need it. Programming requires patience and the ability to handle detail. Women are ‘naturals’ at computer programming.” 22

Already, though, the “masculinization process” of the computing industry was underway. The severe limitations of memory and processing power in the machines of the day demanded Mel the Real Programmer’s wizardry; John Backus described programming in the fifties as “a black art, a private arcane matter … [in which] the success of a program depended primarily on the programmer’s private techniques and inventions.” 23The aptitude tests used by the industry to identify potential Mels consisted primarily of mathematical and logical puzzles, which often required a formal education in these disciplines; even Cosmopolitan magazine, despite its breezy confidence about the absence of sexism in computing, recognized this as a barrier to entry for its readers. An industry analyst argued that the “Darwinian selection” of personnel profiling resulted in an influx of programmers who were “often egocentric, slightly neurotic, and [bordering] upon a limited schizophrenia. The incidence of beards, sandals, and other symptoms of rugged individualism or nonconformity are notably greater among this demographic group.” 24The Real Programmers that the industry found through these aptitude tests were weird male geeks wielding keyboards.

As Ensmenger puts it:

It is almost certainly the case that these [personality] profiles represented, at best, deeply flawed scientific methodology. But they almost equally certainly created a gender-biased feedback cycle that ultimately selected for programmers with stereotypically masculine characteristics. The primary selection mechanism used by the industry selected for antisocial, mathematically inclined males, and therefore antisocial, mathematically inclined males were over-represented in the programmer population; this in turn reinforced the popular perception that programmers ought to be antisocial and mathematically inclined (and therefore male), and so on ad infinitum. 25

The surly male genius, though, was perceived as a threat by corporate managers, especially as the initial enthusiasm over computerization gave way to doubts about actual value being produced for the companies spending the money. A programmer-turned-management-consultant described the long-haired computer wonks as a “Cosa Nostra” holding management to ransom, and warned that computer geeks were “at once the most unmanageable and the most poorly managed specialism in our society. Actors and artists pale by comparison.” 26Managers should “refuse to embark on grandiose or unworthy schemes, and refuse to let their recalcitrant charges waste skill, money and time on the fashionable idiocies of our [computer] racket.” 27

The solution that everyone agreed upon was professionalization. Managers liked the idea of standardization, testing, and certification; it would reduce their dependence on arty individuals practising arcana: “The concept of professionalism affords a business-like answer to the existing and future computer skills market.” 28Programmers wanted to be recognized as something other than mere technicians — the rewards would be “status, greater autonomy, improved opportunities for advancement, and better pay.” 29Within academia, researchers were struggling to establish computer science as a distinct discipline and establish a theoretical foundation for their work. So, “an activity originally intended to be performed by low-status, clerical — and more often than not, female — [workers],” Ensmenger tells us:

was gradually and deliberately transformed into a high-status, scientific, and masculine discipline.

As Margaret Rossiter and others have suggested, professionalization nearly always requires the exclusion of women …

As computer programmers constructed a professional identity for themselves during the crucial decades of the 1950s and 1960s … they also constructed a gender identity. Masculinity was just one of many resources that they drew on to distance their profession from its low-status origins in clerical data processing. The question of “who made for a good programmer” increasingly involved in its answer the qualifier “male.” 30

In 1892, a British colonial official named Sir Lepel Griffin wrote:

The characteristics of women which disqualify them for public life and its responsibilities are inherent in their sex and are worthy of honour, for to be womanly is the highest praise for a woman, as to be masculine is her worst reproach. But when men, as the Bengalis, are disqualified for political enfranchisement by the possession of essentially feminine characteristics, they must expect to be held in such contempt by stronger and braver races, who have fought for such liberties as they have won or retained. 31

Sir Griffin was certain that Bengalis were unfit for political power because they were effeminate, weak, and it was unthinkable that they might “represent … precede … and govern the martial races of India”—that is, certain other ethnic groups within India who were deemed sufficiently warlike by the English. If a Bengali were to demonstrate such aspirations to equality, “then the English, as the common conqueror and master of all, may justly laugh at his pretensions and order him to take the humbler place which better suits a servile race which has never struck a blow against an enemy.” 32

Читать дальше