Samuel Morse had demonstrated his telegraph in 1844—ten years before the publication of Boole’s The Laws of Thought …

But nobody in the nineteenth century made the connection between the ANDs and ORs of Boolean algebra and the wiring of simple switches in series and in parallel. No mathematician, no electrician, no telegraph operator, nobody. Not even that icon of the computer revolution Charles Babbage (1792–1871), who had corresponded with Boole and knew his work, and who struggled for much of his life designing first a Difference Engine and then an Analytical Engine that a century later would be regarded as the precursors to modern computers …

Nobody in that century ever realized that Boolean expressions could be directly realized in electrical circuits. This equivalence wasn’t discovered until the 1930s, most notably by Claude Elwood Shannon … whose famous 1938 M.I.T. master’s thesis was entitled “A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits.” 4

After Shannon, early pioneers of modern computing had no choice but to comprehend that you could build Boolean logic and binary numbers into electrical circuits and work directly with this equivalence to produce computation. That is, early computers required that you wire the logic of your program into the machine. If you needed to solve a different problem, you had to build a whole new computer. General programmable computers, capable of receiving instructions to process varying kinds of logic, were first conceived of by Charles Babbage in 1837, and Lady Ada Byron wrote the first-ever computer program — which computed Bernoulli numbers — for this imaginary machine, but the technology of the era was incapable of building a working model. 5The first electronic programmable computers appeared in the nineteen forties. They required instructions in binary — to talk to a computer, you had to actually understand Boolean logic and binary numbers and the innards of the machine you were driving into action. Since then, decades of effort have constructed layer upon layer of translation between human and machine. The paradox is, quite simply, that modern high-level programming languages hide the internal structures of computers from programmers. This is how Rob P. can acquire an advanced degree in computer science and still be capable of that plaintive, boldfaced cry, “But I Don’t Know How Computers Work!” 6

Computers have not really changed radically in terms of their underlying architecture over the last half-century; what we think of as advancement or progress is really a slowly growing ease of human use, an amenability to human cognition and manipulation that is completely dependent on vast increases in processing power and storage capabilities. As you can tell from our journey down the stack of languages mentioned earlier, the purpose of each layer is to shield the user from the perplexing complexities of the layer just below, and to allow instructions to be phrased in a syntax that is just a bit closer to everyday, spoken language. All this translation from one dialect to a lower one exacts a fearsome cost in processing cycles, which users are never aware of because the chips which do all the work gain astonishing amounts of computing ability every year; in the famous formulation by Intel co-founder George E. Moore, the number of transistors that can be fitted on to an integrated circuit should double approximately every two years. Moore’s Law has held true since 1965. What this means in practical terms is that computers get exponentially more powerful and smaller every decade.

According to computer scientist Jack Ganssle, your iPad 2 has “about the compute capability of the Cray 2, 1985’s leading supercomputer. The Cray cost $35 million more than the iPad. Apple’s product runs 10 hours on a charge; the Cray needed 150 KW and liquid Flourinert cooling.” 7He goes on to describe ENIAC — the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer — which was the world’s first general-purpose, fully electronic computer capable of being programmed for diverse tasks. It was put into operation in 1945. 8“If we built [an iPhone] using the ENIAC’s active element technology,” Ganssle writes:

the phone would be about the size of 170 Vertical Assembly Buildings (the largest single-story building in the world) … Weight? 2,500 Nimitz-class aircraft carriers. And what a power hog! Figure over a terawatt, requiring all of the output of 500 of Olkiluoto power plants (the largest nuclear plant in the world). An ENIAC-technology iPhone would run a cool $50 trillion, roughly the GDP of the entire world. 9

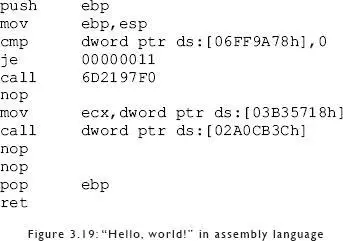

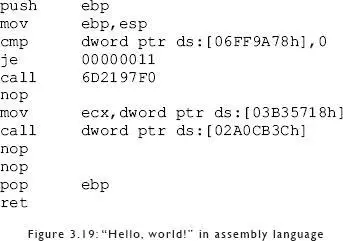

So that smartphone you carry in your pocket is actually a fully programmable supercomputer; you could break the Enigma code with it, or design nuclear bombs. You can use it to tap out shopping lists because millions of logic gates are churning away to draw that pretty keyboard and all those shadowed checkboxes. And I can write working programs because modern high-level languages like C# protect me from the overwhelming intricacy of the machine as it actually is. When I write code in C#, I work within a regime that has been designed to be “best for human understanding,” far removed from the alien digital idiom of the machine. Until the early fifties, programmers worked in machine code or one of its close variants. As we’ve just seen, instructions passed to the computer’s CPU have to be encoded as binary numbers (“1010101 10001011 …”), which are extremely hard for humans to read and write, or even distinguish from one another. Representing these numbers in a hexadecimal format (“55 8B …”) makes the code more legible, but only slightly so. So assembly language was created; in assembly, each low-level machine-code instruction is represented by a mnemonic. So our earlier hexadecimal representation of “Hello, world!” becomes:

One line of code in assembly language usually translates into one machine-code instruction. Writing code in assembly is more efficient than writing machine code, but is still difficult and error-prone.

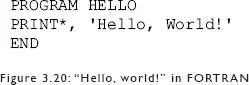

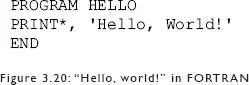

In 1954, John Backus and a legendary team of IBM programmers began work on a pioneering high-level programming language, FORTRAN (from FORmula TRANslation), intended for use in scientific and numerical applications. FORTRAN offered not only a more English-like vocabulary and syntax, but also economy — a single line of FORTRAN would be translated into many machine-code instructions. “Hello, world!” in FORTRAN is:

All modern high-level languages provide the same ease of use. I work inside an orderly, simplified hallucination, a maya that is illusion and not-illusion — the code I write sets off other subterranean incantations which are completely illegible to me, but I can cause objects to move in the real world, and send messages to the other side of the planet.

4 HISTORIES AND MYTHOLOGIES

The American novels I found on the shelves of my lending library in Bombay were dense little packets of information and emotion and culture from across the globe. I consumed them and the values and mythologies they incarnated, and was transformed in some very intimate way. Once I was in America, face-to-face with the foreign, I wrote a novel about another Indian encounter with the Other: about colonialism, about the coming together and clash of cultures. Despite my love for American modernism, it turned out I didn’t want to write a modernist novel. I ended up writing a hybrid book, a kind of mongrel construction which used, in one half, the Indian storytelling mode of magical tale-within-tale and all the sacred and profane registers of classical Indian literature; the other half operated more or less within the mode of modern psychological realism. Colonialism exercised its depredations not only within the realms of economics and politics; an essential part of its ideology was the assertion that Indian narrative modes were primitive, or childish, or degenerate, and that Western aesthetic norms were more civilized and sophisticated. History was progress, the colonized were told, and the West was more evolved. The current state of the world was living proof of this developmental teleology. I wanted to write a book that incarnated in its very form a resistance to this Just-So story about culture.

Читать дальше