I was full of painkillers; I could barely form single words without considerable effort. But I dug down deep and said, “Kimmy,” while she stroked my wrist.

“What did you do, what did you do,” she said.

“I, hhuggh,” I said. The dried blood in what was left of my oral cavity was coming loose, little bits of gummy candy lodged in my throat.

“Sean, you dumb shit, you stupid asshole,” she said. The close air of the room framed her words in such a way that their specific weight, their breathy heft, has never left me.

“I, hnnuggh,” I said, and with great effort used my neck and shoulders to move my head enough to see her where she stood, leaning there, seeing all of me and looking ready to see more if she had to. For reasons that seem obvious to me, I don’t believe in happy endings or even in endings at all, but I am as susceptible to moments of indulgent fantasy as anybody else. When I picture the scene just then, when I remember it right, I imagine a story where Kimmy and I grow up and get married. To each other.

pass through crystal gate

cut central cables

food, water, gauze

sewn patches for light uniform

I spent a few minutes in deep concentration trying to decide what I thought about this: it was the opening four-line salvo of a two-page letter from Chris, and it continued on in this way jaggedly toward its inevitable terminating CH .

invert map

Hansel and Gretel

ration supplies

defogger

knife

It was a mixture of styles: the imperative chosen from the list of available options, the tell-your-own-story tendency that most players settle happily into, the wild compression that made Chris so strange and special. But it was lost in itself here; I didn’t know what he was talking about.

mark signposts if any

flora/fauna

hydrate

circular detours when possible

gloves

bedding

protective glasses

Nobody has any protective glasses; they’re not something I would have thought to include in the game. Nobody needs to hydrate: the movement of the game is simpler than all that. Detours? Those come from my side of the table, not the player’s. I guessed that the second page might contain some one-line summation of what I’d been reading; I thought maybe Chris was fleshing out his experience and letting me in on the process. Instead it continued in the same way:

call mom?

blade

bat

memorize passwords

flint and gel fuel

saline mist

“focus”

check map inversion at intervals

rest in open

love enemies/friends

note tacked to near post

when tower in view.

Saline mist? Gel fuel? Crystal gate? These were touchpoints from somebody else’s dream, traces of the fallout from somebody else’s accident. I pulled REST AND RESTORE from the actual options that Chris had been offered at the end of his last turn. REST AND RESTORE was a placekeeper move of the sort you got every four moves or so; they drew out your time and imparted a sense of depth without moving your play ahead too fast. I knew that some people who’d get that would instinctively take advantage of these moves if they needed to. People don’t play games like mine with a view toward not having anything left to play.

My dad came straight to the hospital from work. When he got here Kimmy was sitting bedside on one of the three-legged rolling stools with the circular seats that doctors use. She was pushing herself back and forth, half a foot this way, half a foot back, rocking. “What have we here?” said my dad, which was something he always said: most of the time it more or less just meant “Hello,” but it was an actual question here.

“Mr. Phillips,” said Kimmy, and she got up to hug him, which was a thing she did to absolutely everybody; it was one of the things I liked about her. But my father left his arms at his sides, leaving Kimmy to squeeze his ribs like a person on angel dust hugging a stop sign. They remained that way for a few seconds; I could only make out the edges of the scene but it made me squirm.

“What do you know about this?” my father said when she’d let him go.

“What do I know?”

“What do you know?” my dad said.

“Probably as much as you know.” She was a little angry now. I could hear it. It was kind of exciting; people were pretty selective about how they let themselves feel when they were in my room.

“That’s probably not — probably not true,” said my dad. “We don’t know anything at all, his mother and me, we don’t know anything.”

I moaned in protest. Kimmy’s fingers brushed my hand, hanging down by the siderail.

“I don’t either!” she said, and then: “What are you even talking about?”

As Dad answered I could hear in his voice that he’d been rehearsing these lines, getting them ready. Sometimes I’d catch him at the mirror in the morning while he shaved, testing out things he might later say to his boss or to his friends at work. When he’s heading toward some specific point, you can’t miss it: it’s in the air. All my life this has given me the creeps.

“We called your parents,” he said. I wished I could see her face from where I lay, wished I could see the response in her eyes. “We think somebody knew something about this. About all this. Before.”

“Before?” she said. I loved her anger, how much she resented my father just then. “I don’t—”

“Well,” he said, “we think you probably do.” When I imagine this scene as part of a movie, the minute of silence after my father says this is extended for an hour or so, and then the credits roll.

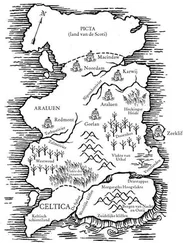

At the northern gate of Camp Oklahoma the capos have gathered around a pit fire. It is late at night and the stars above you shine, huge oceans of milky light. Too dehydrated to stand up, you hunker forward on your knees and elbows, prepared to fight with your fists and your teeth if it comes to that. An outcropping of sage provides partial cover, but if you stand up you will be seen.

Around the fire stand the guards, consulting either a map or some blueprints, it’s hard to tell. In Camp Oklahoma you are adrift, and each turn you take could be the one that leads you back to the same crag wall you landed against when you jumped off the train. No matter how many possible plans of the compound you sketch out in the dirt beneath you, none of them seem accurate, and your days and their stops have begun to blur in your mind. Beyond the soldiers stands the gate, locked but maybe scalable, possibly electrified. The unlabeled bottle of pills that remains from your pharmacy run three days ago presses into your thigh through your pocket as the thirst turns your throat dry. Maybe you can make some kind of a deal. Or maybe you’ll just run straight for the fence.

I must have drifted off into dreamworld somewhere, which would have made me feel ashamed if it hadn’t been something that happened all the time; I couldn’t control whether I stayed conscious or not just yet. “Sean, are you awake?” my father said when the time came for him to make his move.

“Yeah,” I said. I wouldn’t be getting speech therapy until after I’d been sent home; it took me ages to get to full sentences.

“Sean,” he said. I hate it when people say my name again and again, like I’m going to forget who they’re talking to. Over the years I’ve developed a theory that the sicker you look, the more people say your name. “Your mother and I want to talk to you about Kimmy.”

“Here?” I said; it sounded like I was asking if we might have this conversation somewhere else. But my father understood me. I wanted to know if Kimmy was here, if she’d come with them, if she was OK.

Читать дальше