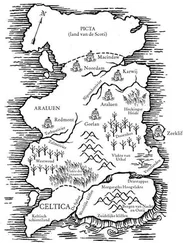

As you rappel down cascading chains of mutated ivy, you taste the air. It’s different down here. The all-pervasive dust that clots your lungs begins to clear itself out in coughing spasms whose violence subsides as you descend. The smell of the ivy restores your hope in the journey. Your feet ache to touch fresh ground below.

The descent to the upper catwalk takes two hours, which are spent in a crisscrossing pattern among available vines. Your arms and ankles burn when you land; you tear off a handful of leaves when your feet hit the steel grating and stuff them into your mouth. They are moist and bitter. A new clarity gradually seizes your vision as you cast your gaze around and beneath.

You’re inside a cylinder, a silo some thousand yards high; from your perch you can see that it continues down into the earth for many thousands more. It must have taken years to dig so deep. To build the broken network of platforms you must now navigate. To construct, from available scrap, sanded smooth and disinfected to keep the interior clean, the descending entryway to the kingdom beyond.

When I got home my mom asked me what Ray’d had to say. That was how she put it: “So, Sean, did you have a good day, what did Ray have to say?”

“He said guns are awesome,” I said. It was a mean thing to say, and I was immediately sorry, but it was too late. My mother’s shoulders stiffened, and she held her hand at her chin, two fingers pressed across her lips.

“Sean, you don’t—” she said, and then she stopped to draw in some breath and try to keep her composure. “You don’t understand,” she said finally. Like most things she started to say about the accident, this went nowhere: there were too many places for it to go, so when it opened out onto its great vista of sad possibilities it just rested there, frozen by the view.

“I do, I do, Mom,” I said. We were standing in the living room; Dad was in the bathroom. “Ray said I had to respect guns, is all, it was—”

I took my mother’s hand between my hands. I felt like a very old man who had lived for a very long time; I knew I wasn’t that old man, not really. I hadn’t actually come into possession of any great wisdom, hadn’t been on a quest that had seasoned me and invested my words and actions with meaning. But the sheen of it, the reflection maybe of a wisdom I might someday still attain, was visible to me for a second, and I felt the weight of what I’d done to them press against my chest like a heavy hand. “It was a funny thing for him to say, is all.”

Mom wanted to meet me out there in the space I was trying to clear. But she couldn’t do it, and I couldn’t blame her then, and I don’t now. There was too much wreckage in that space for her to stand.

My father came in then and saw Mom crying, and he was mad. He must have been mad already, after taking me down to Ray’s with some uncertain hope in mind, looking for some conclusive moment and not getting it: I was pretty sure about this. Instead it had been another incident without clear lessons. “Why do you have to make your mother sad?” he said in his louder voice, the one he saved for when he wanted to be heard. “Haven’t you done enough—” he said, his stutter catching him at a crucial moment; I could see it make him even angrier. He kept his eyes firmly on mine. “Done enough already?” he said at last.

“It was an accident,” I said, and Mom put a hand on his shoulder and said it was really OK, that there’d been a misunderstanding, and Dad’s face did that thing it had recently learned to do: where his expression skidded across a sliding drift from anger to sadness to something else that didn’t quite have a name, all in the course of a few seconds.

“OK, Sean,” he said, “sorry, sorry to yell.” We stood in our little triangle and then the doorbell rang; Dad had ordered some pizza for dinner. He put out some plates with a knife and fork by mine, and we all sat down to eat. Mom asked him the same question she’d asked me, in the same words—”What did Ray have to say?”—and Dad tried his best to explain why he hadn’t really said much to Ray about liability and so forth, and Mom didn’t say anything back, and then after a while Dad got up from the table and turned on the evening news with the volume too high.

Conan the Barbarian has no parents, as far as I know, but in my mind he was my model: trying to stand strong and brave, sword in hand, black hair flowing. In truth I have very little hair on my head now, and the hair I do have tends to clump in stringy clusters, but if my eyes are closed and my concentration is strong I can form a different picture of myself in my mind, so this was what I did, standing by the waist-high desk where the phone was. I closed my eyes and I concentrated. Dad was getting ready to tell me about the funeral plans, I knew. I could make it easier for him if I tried hard enough. It isn’t really much of a mystery, this occasional need I have to comfort my father. I did something terrible to his son once.

“Grandma lived a long time,” I said. Ten-plus years since Dad took me down to Ray’s on that open-ended mission where nobody got revenge and nothing got resolved, and a whole lot of empty ground in the space from now to then. I have a theory that the less you say when someone dies, the better. Leave everything as open as you can.

“Thanks, Sean,” he said. “For me this is hard, I—”

“Terrible,” I said.

“No, no,” he said, “that’s — it’s all really hard, but what I actually — I—”

“Not—”

“No, what — Sean, I don’t like to say this; I know you loved your grandmother, and she loved you, but we—” Pausing here. Some things you practice a few times but it doesn’t make them any easier. I could hear it now. “We don’t think you should come to the funeral. I know that’s—”

He just left it there for a second.

“It’s really hard to—”

When anger rears up in me I have a trick I do where I picture it as a freshly uncoiled snake dropping down from the jungle canopy and heading for my neck. If I look at it directly it’ll disappear, but I have to do it while the snake’s still dropping or it will strike. This sounds like something they’d teach you in therapy at the hospital or something, but it’s not. It’s just a trick I found somewhere by myself. Once you’ve looked at a deadly thing and seen it disappear, what more is there to do? Walk on through the empty jungle toward the city past the clearing.

“It’s OK, Dad,” I said, evenly. I took stock of how I really felt: found all the various threads, saw which way they all ran. “Dad, it’s OK. I get it. It’s all right.” And I do get it: I am not a welcome presence at a funeral, no matter whose it is. If I let myself stay mad about that I will go insane.

On the other end my father, now an orphan, was crying.

“Thank you, Sean,” he said. “I don’t mean to be awful to you. It’s just — it’s hard for me to ask, it’s really hard. Your grandmother was so happy back in those early days, back when—”

The little silence that followed wasn’t my dad’s repetitive stutter. I could hear him entering a space he usually tried to avoid, finding himself on the other side of a door he wouldn’t normally open. I followed him in.

“When you were a baby,” he said, at last.

He sounded like he was choking. “It’s OK, Dad,” I said. “It’ll be OK.” CLAN SCARECROW, I saw penned in neat script on a little card inside my head.

I stood with the phone at my ear and tried to think of something to say. My father plays his cards close to his chest, but I felt like there was an opening here, a portal: a seam in the surface I was supposed to notice and pull open and climb through. That was why it was Dad calling, not Mom. So I took a quiet breath and put on my grown-up voice, the one I use when somebody looking for me gets ahold of my phone number.

Читать дальше