I’d sent her a little note in reply. It was both sweet and painful to me to think of how much L+C meant to each other, how their lives seemed almost made for each other. When I was in high school, I’d only ever had two girlfriends: one for almost no time at all — two weeks early in freshman year, at the way station between junior high and the new social order being established at high school — and Kimmy for even less time than that, really just an unsure day or two right before the accident. Technically, I guess, she had still been my girlfriend when she visited me in my bandages at the hospital, but those visits were of a different order. I understood a little about how good it must feel to have someone who loves you out there in the wilds of high school; for a few days I’d known what that was like, too. But what Kimmy meant to me in the aftermath was something different and higher, a singular thing in the world with no readily available points of comparison. She was just sixteen, but she had the stomach to stand near a smoking wreck.

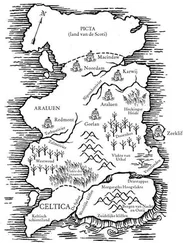

On the Xeroxed move I took from the file cabinet, I wrote: Good work to both of you Carrie. It’s safe behind the dumpster. Tell Lance when he gets home that you kept him from harm. I remember feeling a little guilty, because while it’s possible to make a move that kills off your character within the game, it’s almost never possible to walk straight into a fatal trap; telling somebody their game is over is a bad business move, and I’d known that before I ever took out the first ad. So staying put until dark was a good move, one that would advance the player painlessly toward the short-term objective of reaching the city limit unharmed; there was no real danger. But the wrong move could have delayed the team until winter, scaling hospital exteriors to get at the one uncontaminated bottle of disinfectant or a snakebite kit. There was a colony of snakes in the ditch just a few hundred yards away: she might have chosen HEAD FOR THE DITCH instead of REST BY THE DUMPSTER. So I hadn’t lied. I had just played up the bright side.

When Lance got home and sent in his moves, he was excited. I remember his excitement, how I could see it in the way the pencil dug into the page. I was piecing together what I knew about him while picking out clothes for the hearing. Vicky had come in to help me dress. I didn’t need her help — I can dress myself — but I was grateful. Sometimes I wondered what Vicky made of my work, since she never asked me about it and I didn’t usually volunteer much; our conversations stuck mainly to simple things like food or the weather or how we were feeling. She told me about her family sometimes. If she found me at my work she mostly left me at it.

It was difficult, that day, to remain in the moment. I wanted her to know how I felt, thinking of Lance where he was now: in a place called Casa Central, some physical rehabilitation center for adolescents. Most of his fellow patients had survived more sudden traumas than his: car accidents, house fires. His problems had a better shot at total resolution, but in the immediate present they were as bad as anybody’s. He’d spent days down in a shallow pit without food, with only forming ice to suck for water. Now he lay on a burn recovery bed all day hoping that feeling would return to his legs from the knees down, his face salved and wrapped, everybody praying that enough attention would encourage some of the skin to grow back.

As best as I can put it together, this is what I can tell you about Lance Patterson: he was born to a couple in their mid-twenties who had been married for several years. His father worked the evening shift at some Winter Park assembly line that made parts for machines; his mother was a substitute in the grade schools. His family was a good family; they weren’t rich, but they all lived together and stayed in one place. Of course I only knew him through the mail, but I imagined him as an awkward boy with too much energy. His teachers liked him, and they told him so; I know this because he mentioned it once when he said that the other kids his age didn’t like him but his teachers were nice. He spent his afternoons after school hanging around the house, watching television and keeping himself entertained. He had a few friends, all casual, but was personally somewhat guarded; when Carrie came into his life, a corner of the world he’d only ever dreamed about was opened for him. I learned about this corner of his world when he brought her into the game, which he’d only been playing for a few months. Is it OK if I have a partner playing with me who can just start where I’m at? he wrote. Can we just say I found her hiding somewhere? I didn’t see why not; I couldn’t write a special turn for it, but I wrote at the top of his next turn: You have been joined by a young technician who can help you tap the aquifer.

He was not unusual in sending me bits and pieces of his life; that, in part, was what contributed to my horror at the whole situation. There might have been others like him about whom I’d never heard, people whose play had taken them into lightless hallways: What of them? They found their way out and disappeared. Or they never said anything and kept on playing. What did I know about these people, about anybody anywhere whom disaster hadn’t struck? There was Chris, he was all right. But generally the only way we ever know anything about anything is if something goes wrong. Knowing this is hard for me.

“This is a picture of a boy named Lance,” I said to Vicky, out of nowhere, while she was straightening things up. “He plays that game you always see me working on.” I felt like a man leaving a spaceship for the surface of a new planet; it is pretty rare for me to feel that sort of need so many seem to have, that irresistible desire to tell somebody else what they’re thinking. I hadn’t talked to Vicky about the lawsuit; for several reasons I tend to keep my conversations with people limited to basic, pleasant things like the weather or which kind of macaroni and cheese tastes the best.

“Oh?” said Vicky. Back in my own trauma ward days I knew several social workers who could have learned a thing or two about reflective listening from Vicky.

“Yeah,” I said. She was making my bed for me hospital style, tight corners and accordion folds. “He’s in the hospital now but he’s been playing Trace Italian for almost three years. Him and his girlfriend. She died.”

“I’m real sorry,” she said, “to hear it.” I could see her taking the measure of me, noticing how talkative I was today. “How is he getting by, now?”

“He’s—” I looked for the word, and for a few seconds while I looked, I considered her question, the depths of understanding that seemed to have formed its words: How many people had she taken care of whose problems involved getting by or not getting by in so many hundreds of different degrees? “He’s managing,” is what I came up with. She came over and sat down beside me, getting her dressing-changing things together on a tray, and she waited for me to continue.

“He went a long time without food or enough clothes to keep him warm,” I said. “He was in a place a long way from his home and he didn’t know how cold it got there, and by the time he figured it out, it was too late. He tried to save his girlfriend, they say, but she was trying to save him, too, and she didn’t make it. They liked to read the same books together, and see the same movies and talk about them; he used to write to tell me about the things they liked to think about. I don’t think he really knows how to think a few steps ahead, you know.”

“Young people can’t think ahead,” she said. She was opening up some Betadine swabs.

I laughed my little wet throat-laugh. “I know,” I said; “you know I know. I keep hoping he won’t blame himself too much for being stupid. I mean, he is a little stupid, I think, but to me that’s not a bad thing to say about a person. I’m a little stupid but I’m all right. Lance is young and stupid though, I guess. That’s two strikes.”

Читать дальше