There was for example a postcard bought at the Flying J, a point of origin determined from receipts found in the abandoned car. It had been written at a Qdoba, though, from whose window one could see the highway, and it had then been addressed to me; they knew this because the text on the postcard said so, and also because detectives had visited the Qdoba in question in the course of their investigation, where they’d asked the manager whether he remembered some teenagers stopping through and writing a postcard either before or after or during their lunch. Naturally the manager of the Qdoba didn’t remember any particular teenagers who’d had lunch there, but he did volunteer to ask his employees whether any of them remembered anything. One of them, eventually, did remember something, or thought he did, and so the claims the postcard made for itself were allowed to be discussed without anybody arguing about it.

It was numbing, but only down to a certain level, past which there can be no numbness. Lance and Carrie had written: Got this postcard at a flying j but we’re at qdoba now. next time you hear from us we will be inside!! There was no need to reassemble the circumstances of the postcard’s purchase, its meaningless life on its way to me; it did that by itself. All that was left for me to do with it was hold it in my hands and answer a question or two: yes, the business to which this postcard is addressed is Focus Games; yes, I do business under that name; yes, I notice that there’s no stamp on the card; no, I couldn’t guess why it wasn’t stamped and sent (I wanted to guess, because I had some guesses, but my attorney had advised me against trying any of my guesses out loud). No, as I had told them all before, I had never been to Kansas. No, I did not know why Qdoba. No, I had never eaten at such a place, or mentioned it in passing in any of my correspondences with customers. Yes, I understood why they were asking me about the Qdoba. They were asking me because it was the last place anybody had ever seen Carrie alive.

Carrie’s parents had flown in from Orlando. They’d been staying in a motel by the freeway for weeks. It was a safe bet that their lawyer would have warned them by then about what to expect from my physical appearance, but unless you work in the medical field somewhere, you can’t really be prepared to meet me, I don’t think. It is always a surprise. It’s just not a thought people can get their teeth around, having to brace themselves to meet someone at whom it will be difficult to look while he’s talking but whose speech they will strain to understand.

They were brave. My lawyer and I entered the room; she nodded her hellos to the prosecutor and the judge while I kept my head low like I always do, and then we took our seats on our side of the table. Carrie’s parents — Dave and Anna; Anna and Dave: I could never decide how to pair them in my mind — fixed me with a look that I imagine had taken some practice, but which was sincere. There was not a whole lot of anger left in it, though traces lingered here and there: in the crow’s-feet by their eyes and the bags under them, say. In the way their eyebrows didn’t rise when they nodded. But the main thing their expressions indicated was a sense of duty. It pained me to think about it.

The judge read out a few things about the nature of pretrial hearings and about what we were here to do, and then things opened up a little: it was like a refereed argument between people who weren’t allowed to address each other directly. Their lawyer stated what their case essentially amounted to — that I’d contributed to the endangerment of a minor both directly and indirectly, and that this had resulted in the death of one and the grave injury of another: manslaughter and attempted manslaughter — and mine tried politely to say that you’d have to be crazy to blame anybody besides Lance and Carrie for what they’d done.

I focused on my breathing, because I knew my lawyer was eventually going to read my statement, and I wanted her to get it over with; I’d hoped it would come out right at the beginning, so that Dave and Anna could either accept it forgivingly or reject it scornfully, and then I’d at least know where I stood. Until they’d heard what I had to say, I figured, there wasn’t really any way of seeing their hand. It was impossible for me to imagine any scenario other than those two: total understanding or total denial. Either they’d get what I meant, or they’d shut their ears to it and we’d head down our sad road together. I didn’t see a third way.

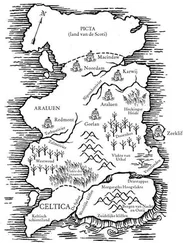

Where the railroad used to run, there’s a little less overgrowth. As you travel, you keep your eyes on the ground ahead of you, trying to make out a path. Hours turn into days. You become a human bloodhound. You notice things others didn’t as they tried and failed to walk the path that now is yours. As you progress the path becomes less clear: with every less clear point you know you’re going beyond the places where the others lost the trail. Stopping to rest, you see a spot where plants seem to grow higher. If they have followed your path faithfully, bounty hunters will be here within the hour. North lies Nebraska.

This turn came accompanied by one of my occasional bonuses, a status upgrade. It was an aluminum coin; I’d had fifty of them minted for me by one of the companies that made tokens for video games, back when there’d been a video arcade in every mall. There was a picture of a dome rising from an empty plain on one side, and on the other, it said PATHFINDER. I had only ever had to send out three of these coins over the years. Two of them were in the hands of longtime players in distant places. The other was in a plastic bag labeled EVIDENCE on the table in front of me.

I felt embarrassed when the text of the turn was read out loud at the hearing; most of Trace Italian’s latter turns were essentially first drafts, since hardly anyone ever saw them. They were turns in theory, not practice. Some were actually relics from all those long days in the hospital, formulae I’d memorized to keep myself from going insane during nights when I couldn’t sleep because of the pain in my jaw, or from days when the ringing in my ears demanded that I focus very hard on something until the sound died down. None of them were anything I’d looked at in years until Lance and Carrie’d gotten to them; they were crude artifacts to me now, or like somebody else’s work imitating mine. Given the whole thing to do over again, I might have written the late moves better, focused harder on the phrasing. But I hadn’t, and now they were cast in stone. I’d thought once or twice about revisiting them, but I didn’t have the stomach for it. Trace Italian had existed long enough to have earned self-determination. I didn’t feel like I had the right to revise it. That right belonged to the younger man who’d written the game, and that younger man was dead. Besides, there were people playing toward the latter moves; the moves had to remain as they were in case anyone ever got there. It seemed almost a moral question.

Like all turns, this one ended with the player’s options presented as an unnumbered list of possibilities in typewritten capital letters, each possible next move occupying its own line of type. When, in the hearing room, the turn was handed around the table for all to examine, I smiled a little inside. I had tried, so long ago, to limit the player’s options if he ever came to this pass. I had failed, but the effort seemed clever.

FORAGE FOR ROOTS

FOLLOW THE RAILROAD

WAIT FOR HUNTERS

NORTH TO NEBRASKA

When I was a child, my mind wandered a lot, and most often it would wander to the dark places, as though drawn there by instinct. It found them again now. I saw Lance and Carrie freezing in the middle of the hard Kansas night. I imagined their hunger. I remembered skimming the autopsy report: Carrie died early; her coat was thinner. What had it been like for Lance, lying in the dark, waiting to be next? The pit they’d dug for themselves: Had it bought them some time? Or had the energy they’d wasted digging shortened the time they’d had left? Does a person gasp like a dying old man when he’s dying of cold, or is it different? Did they see their nail beds going blue, and feel panic, or had their minds gone past the point of panic to that self-drugged state where everything looks cool? And why hadn’t they gotten up and run back to the highway — no energy left? Still convinced they’d find something? Did both of them want to bolt from the scene but neither one want to blink first? Their young, perfect bodies, wasted, squandered, covered in the end with wet grass they’d pulled into the pit from the surrounding plain. Trying to put it off. Children. Children in the grip of a vision whose origins lay down within my own young dreams, in the wild freedom those dreams had represented for me, in my desperation: to build and destroy and rebuild, to create mazes on blank pages.

Читать дальше