It was a shot in the dark, but from the way Stella reacted, grimacing—the tears were gone—Alice knew she’d guessed right.

“Nobody special.” She touched her right eye again. “But that kid Zack, um …”

When she uttered the name, Alice knew everything. Zack with his baseball cap on backward. Zack from the ticket line at the Regal Cinema and the Bollywood movie, who had gone to NYU film school and wanted to make a Bollywood movie himself with big-name American actors. Zack in the T-shirt that said Choose Death , whose father was (so he said) a connected Hollywood lawyer, who was staying at the Taj Mahal Hotel. Zack with his cell phone that worked in India for U.S. calls—Stella had called her mother on it. Zack whose father knew Bill Clinton.

“You said he was a brat.”

“That was a first impression. He’s got a spiritual side, plus he’s really funny.”

“He just wants to nail you.”

Stella looked appalled and on the verge of crying again.

“He already has!” Alice said. “You’re screwing him. That’s what you were doing the other night when we were at that club and you said you had a headache and went back to that fancy suite his father got for us.”

Hearing the raised voices, and especially You’re screwing him , some Indian men paused and drew closer to listen to the two women, whose faces were flushed.

When one pressed close to her, Alice turned on him and said, “Do you mind?” and the man stepped away but remained within earshot.

“I told you it’s a long story.”

“It’s not! It’s a short story. You met a guy. He said his father was in India to go to that luxury spa near Jaipur.”

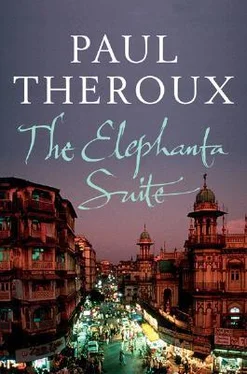

She saw it all. Zack had gotten his father to pay for them to spend one night at the Elephanta Suite, and afterward Zack had invited Stella to travel with him and his father to the spa where Bill Clinton had stayed. Stella was as interested in the father as she was in Zack—perhaps more so, since spoiled children were always looking for protectors, who would let them have their own way. Now Alice was glad that Stella—shallow, selfish Stella—was not coming. She began to laugh.

Hearing her laughter, the Indian men stepped closer, as though to inquire, What is so funny?

Alice said, “I think you’re right. This is like one of those partings on a railway platform in a movie.”

And Stella looked happier.

Right at the beginning of the trip they had agreed: no boys, or if there had to be boys, no relationships. Also, no expensive hotels, no patronage, no accepting drinks from strangers. We’ll pay our own way, even if it hurts.

And of all people, Zack. Now Alice remembered with scorn how Zack had passed an image of Ganesh, the elephant deity, fat and cheerful and beneficent, bringing luck to any new enterprise, seated on his big bottom, with jewels on his domed head and his floppy trunk and his thick legs.

“He looks like a penis,” Zack had said.

“I guess you haven’t seen too many penises,” Alice said.

Stella had looked alarmed and glanced with concern at Zack, who said, “More dicks than you have, girl.”

That meant, You’re plain. When she was heavy at Brown, she heard fat jokes, and now that she had lost weight, she heard ugly jokes. And the amazing thing was that people actually said them to your face, as though there was some subtlety in them, rather than: You’re fat, you’re plain, you can’t get a date. And they also said them because, if you were plain or heavy, you were supposed to be strong and have a sense of humor.

Now she remembered Zack saying, “Want to text-message your folks?” And she smiled angrily at Stella and said, “Aren’t you the clever one.”

Meaning, You’re not clever at all. But Stella, with the pretty girl’s deafness to irony, took it as a compliment.

“Maybe we can hook up somewhere,” Stella said.

“You’re on your own now, girlfriend,” Alice said.

She had to summon all her strength to say it, because she knew that Stella was taken care of. As soon as she spoke, she was breathless.

Seeing that the foreign women had become more conversational, with lowered voices, the Indian men lost interest and wandered away, down the platform where people were pushing to enter the train. Suitcases were being hoisted through the windows of the coaches, families were hurrying to board, red-shirted porters carried boxes in wheelbarrows.

Now a man approached with a clipboard and sized them up. He said, “Boarding time.”

Alice showed her ticket and said, “She’s not coming. She found another friend.”

Stella began again to cry. She hugged Alice and said, “I love you, Allie. I have to do this. I can’t explain.”

“This is a bad movie,” Alice said, and broke away.

After she boarded and found her seat, she saw Stella outside, gaping, looking cow-like. Stella leaned and waved and remained watching until the train pulled away. She was still tearful, but she was meeting Zack and staying at Zack’s fancy hotel, and it was Alice who was on her own.

But no sooner had the train pulled out of the station and was rumbling past the tenements and traffic of the Mumbai outskirts than an unexpected feeling came over Alice, glowing on her whole body: she was alone and liked it. Free of Stella, she felt stronger and more decisive. She could do whatever she wanted without consulting her fickle friend. Just fifteen minutes into the twenty-four-hour trip, she realized that Stella had been a much bigger burden than she’d imagined. Now Stella was at risk and it was she who was happy in the swaying train, like being in the body of a bulgy creature that protected her while plodding forward in the heat.

With the whole day ahead of her, she sat by the window and watched India slip by in a stream of simple images—women threshing grain on mats, men plowing with placid oxen, children jumping into muddy streams, clusters of houses baking in the sun, here and there a level crossing where a blue bus or a man on a bike was stopped by a passing train. These human sights became rarer, for after Poona there were only fields or stunted trees or great dusty plains to the horizon, an India Alice had not seen or read about before, and because she was not sharing it with Stella it was all hers, a secret disclosed to her, a discovery too that India was also a land of empty corners.

And so all that hot day in the hinterland of Maharashtra Alice marveled at this revelation of big, yawning India. It was the antithesis of crowded, damp, and noisy Mumbai, the words “critical mass” as a visible image. She liked what she saw now for being unfinished and unpeopled. Stella knew nothing about it—might never know, for Zack harped on about being a city person, talked importantly about setting up a movie, and you could do that only in a big, stinking city.

“You can have him,” Alice said clearly, still at the hot window.

She was startled when a voice said, “Pardon?”

The seat where an elderly Indian woman had been sleeping wrapped in a thin sheet just a moment ago—or so it seemed—was now occupied by a young Indian man. He was fat-faced and bulky, with big brown eyes, a lovely smile, and wore a clean, neatly pressed shirt. He was sitting cross-legged, barefoot, where the old woman had been, and both his posture and his face conveyed the assurance that he was harmless, even if a bit innocent and fearful. He sat with his chubby fingers locked together in a patient posture of restraint.

“I was just thinking out loud,” Alice said.

“Talking out loud,” the young man said.

“Not exactly,” Alice said. “The thought was in my head but it somehow got turned into some words.”

“Something worse?”

“No. Some words. The thought became a statement.”

Читать дальше