Paul Theroux

The Pillars of Hercules

To the memory of my father,

Albert Eugene Theroux,

13 January 1908–30 May 1995

Have you ever reflected on what an important sea the Mediterranean is?

— James Joyce in a letter to his brother Stanislaus

The Mediterranean is an absurdly small sea; the length and greatness of its history makes us dream it larger than it is.

— Lawrence Durrell, Balthazar

1 The Cable Car to the Rock of Gibraltar

People here in Western Civilization say that tourists are no different from apes, but on the Rock of Gibraltar, one of the Pillars of Hercules, I saw both tourists and apes together, and I learned to tell them apart. I had traveled past clumps of runty stunted trees and ugly houses (the person who just muttered, “Oh, there he goes again!” must read no further) to the heights of the Rock in a metal box suspended by a cable. Gibraltar is just a conspicuous pile of limestone, to which distance lends enchantment; a very small number of people cling to its lower slopes. Most of them are swarthy and bilingual, speaking intelligible English, and Spanish with an Andalusian accent. Mention Spain to them and they become very agitated, though they know that as sure as eggs are huevos the British will eventually hand them over to the King of Spain, just as they chucked Hong Kong into the horny hands of the dictator of China.

The Rock Apes of Gibraltar are Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) , the only native apes in Europe. The apes are still resident, and have lived there longer than most Gibraltarian families. There is a social order among the ape tribes, as well as ape rituals that are bizarre enough to be human. Ape corpses and skeletons are never found on the Rock. Somewhere in the recesses of this rock that looks like a mountain range there is said to be a secret mortuary established by the apes; ape funerals, ape mourning, ape burials. The apes are well established, but disadvantaged — unemployed, unwaged, destitute welfare recipients. The municipal government allocates money to feed them.

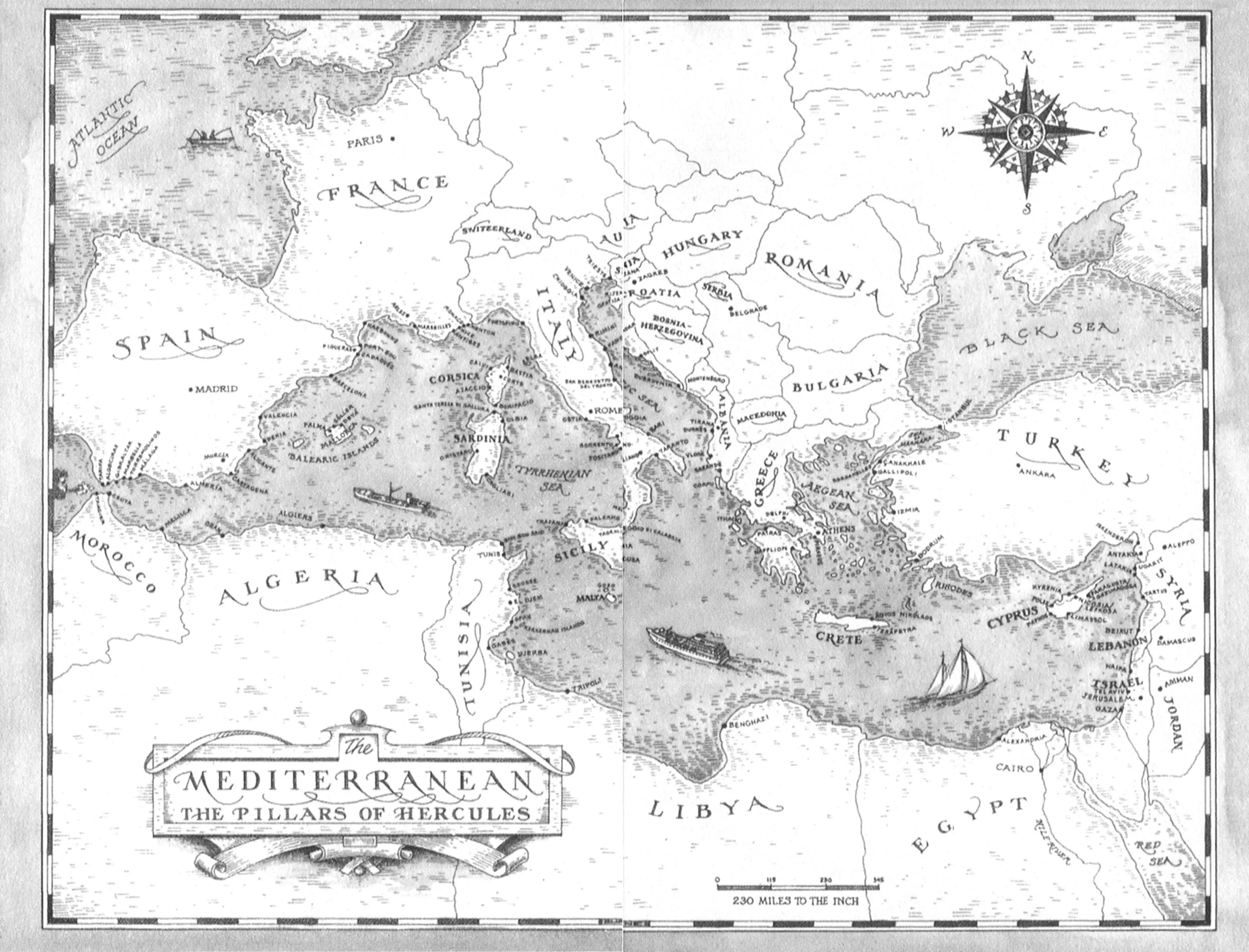

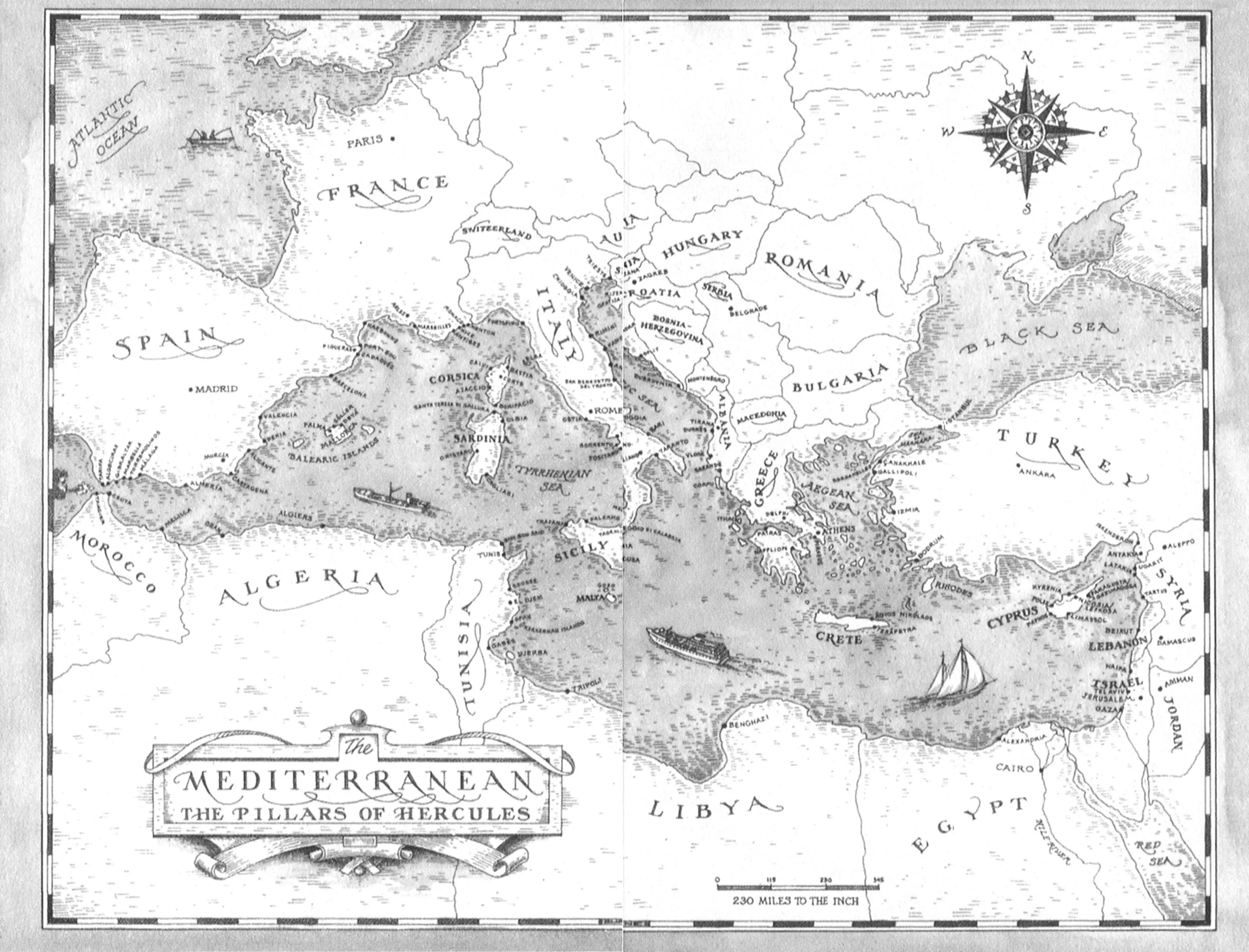

But there might be darker motive in this food aid. A powerful superstition, held by locals, suggests that if the apes vanish from Gibraltar, the Rock will cease to be British. For hundreds of years — since 1740, in fact — the apes have been mentioned by travelers — Grand Tourists, in whose footsteps I was following. Yet Gibraltar has been visited almost since Hercules, patron of human toil, flung it there on his journey to capture the Red Oxen of Geryones, the monster with three bodies (Labor Ten). He tossed another rock across the straits, Ceuta in Morocco. These two promontories, Cape and Abya to the Greeks — the Mediterranean bottleneck — are the twin Pillars of Hercules.

My idea was to travel from one pillar to the other, the long way, with the usual improvisations en route that are required of the impulsive traveler; all around the Mediterranean coast, the shores of light.

“The grand object of traveling is to see the shores of the Mediterranean,” Dr. Johnson said. “On those shores were the four great Empires of the world; the Assyrian, the Persian, the Grecian, and the Roman. All our religion, almost all our law, almost all our arts, almost all that sets us above savages, has come to us from the shores of the Mediterranean.”

“Our” of course is as questionable as “savages,” but you get the idea. A great deal happened on this coastline. It was not until the second century B.C. that the Romans sailed through the Pillars of Hercules. The reason for this late, if not timid, penetration of the straits was not the current, nor was it the inconvenient westerlies that blow through this narrow opening of the inland sea; it was the Mediterranean notion that nothing lay beyond the pillars except the Garden of the Hesperides and the lost continent of Atlantis, and hellish seas.

The pillars marked the limits of civilization, “the end of voyaging,” Euripides wrote; “the Ruler of Ocean no longer permits mariners to travel on the purple sea.” And later, in the second century B.C., Polybius wrote, “The channel at the Pillars of Herakles is seldom used, and by very few persons, owing to the lack of intercourse between the tribes inhabiting those remote parts … and to the scantiness of our knowledge of the outer ocean.”

Beyond the pillars were the chaos and darkness they associated with the underworld. Because these two rocks resembled the pillars at the temple to Melkarth in Tyre, the Phoenicians called them the Pillars of Melkarth. Melkarth was the Lord of the Underworld — god of darkness — and it was easy to believe that this chthonic figure prevailed over a sea with huge waves and powerful currents and ten-foot tides.

The point is not that the Mediterranean peoples had never ventured westward through the straits, but that they had dared it — the Phoenicians had reached Britain by a sea route — and verified that it had a wicked and destructive turbulence. From this they conceived the idea that nothing useful existed past the straits, only the spooky Mare Tenebrosum, the dark and dangerous ocean which lay beyond the Middle Sea, a purple river of furious water. The Greeks named this the Stream of Ocean. It circled the earth at which they were privileged to live at the center, its precise location at Delphi, where a stone like a toadstool marked the Navel of the World. Mediterranean, after all, means “middle of the earth.”

The surface current moves through the straits at a walking pace to the east, streaming through the fifteen-mile-wide pillars into the Mediterranean; but two hundred and fifty feet below this another sub-current rushes in the opposite direction, westward, into the Atlantic, pouring over the shallow sill of the straits, “that awful deepdown torrent,” Molly Bloom murmurs in her bedtime reverie. The unusual circular exchange of water at the straits is the only way this just-about-landlocked sea is kept refreshed and alive. Very few large rivers flow into it. For thousands of years, until the Suez Canal was opened, to the strains of Verdi’s Aïda , in 1869, the Straits of Gibraltar—“The Gut,” to the English sailors, “The Gate of the Narrow Entrance” (Bab el Zukak) to the Moors — was the only waterway to the world.

Even so, the Mediterranean has an odd character. It has almost no tides at all, and except for a whirlpool here and there (notably at Messina), an absence of distinct marine currents. It is dominated by winds rather than currents, and each wind has a name and a series of specific traits: the Vendaval , the steady westerly that blows through the Straits of Gibraltar, La Tramontana , the strong wind of the Spanish coast, La Bora , the cold wind of Trieste, le Mistral , the cold dry northwesterly of the Riviera, and so on, through the Khamsin , the Sirocco , the Levanter , and about six others (often the same wind, with a different name) to the Gregale , the northeast wind of Malta that blows in winter and was probably the wind that caused Saint Paul to be shipwrecked on the coast of Malta, as described in the Bible (Acts 27–28).

It is not a sea that is affected by the phases of the moon — it has moods rather than monthlies. Its nervous character has been mentioned by sailors, and its colors — purple, wine-dark, and its blueness in particular. The Mediterranean was the White Sea to the Greeks — the Turks still use that name for it: Akdeniz , “White Sea,” and the Arabs use a variant, “The White Central Sea.” If the oceans can be compared to vast symphonies, the German traveler Emil Ludwig has written, the Mediterranean “is subdued in a way that suggests chamber music.” It is tentative, and its waves with their short fetch, and its strange swells, are unlike any found in the great oceans.

Читать дальше