Then he heard another rat. He stamped his foot and turned to frighten it.

“Sir.”

Indru—her dress and shoes so white in these shadows.

“How did you find me?”

“I follow, sir.”

She bowed to him. She looked older with the shadows on her face, her white cotton dress glowing. Her stillness alarmed him, and her accent seemed stronger in the twilight.

“May I be seated, sir?”

He was sitting on a coil of rope on a giant spool the size and shape of a tractor tire. Still, he was impressed by her formality.

“Go ahead.”

“Thank you, sir.”

Was it her formality, the mode of her politeness, that made him feel, if not powerful, then dominant—in charge in this lonely place?

“Indru,” he said.

“You did not forget my name.”

“What do you want?”

“I am so hungry, sir.”

It was a terrifying statement. He put his hand into hers. Her hand lay open on her lap, small, though her palm was hard, almost coarse, and her skin like that of a scaly little animal. She said she worked in a salon, but perhaps she also did some sort of hard work? Her stiff stubby fingers closed on his hand—she was trying to show him some affection.

“You’re a nice girl, Indru.”

“Thank you, sir.”

With his free hand he touched her thigh through her loose dress, hiking it up slightly. He felt the skin just above her knee and slipped his fingers around her thigh, where she was warm, as though holding a fresh piece of meat, even sensing that this smoothness would taste good.

She did not resist, yet she made a sound in her throat, swallowing, as if bracing herself, the sort of sucking breath a person draws before taking a risk.

Hearing a rustling sound, he saw in the dim light a rat nibbling a broken blossom that was easily visible because of its white petals. But everywhere else it was dark in the alley. The only available light was the patch of sky above the lane and the twilit harbor framed by the end of the warehouse.

“May I kiss you?”

“Why not, sir?”

Her willingness to kiss seemed like the proof she wasn’t a whore.

He kissed her lips, loving their softness, and he marveled at the risk he was taking. But she had followed him here, the way a homeless animal seeks comfort. He remembered, I am so hungry, sir , and he dug in his pocket for the small soft pouch and the ring that he often fingered, hating the memory of it.

He had to do it now, before anything happened. It was a gift, not a fee. He put it into her hand. She took it without looking, slipped it into her pocket.

“Do you like me?”

She seemed to hesitate. Was it his searching hand that disturbed her? After a reflex of resistance, she allowed it.

“Yes, sir.”

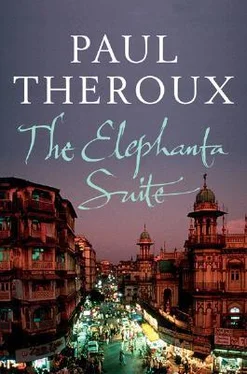

Now, looking down at the Gateway of India from the boardroom at the top of Jeejeebhoy Towers, he saw the warehouses, the docks, the rope works, Apollo Bunder, the Taj Hotel, even the corner window of his suite, the steamy streets he had hurried through afterward, hot with exhausted desire. He could see beyond the promenade where the old woman had led him, and a rooftop that might have been part of her house. Laid out before him was the map of his past three days—transforming days. He did not know what to make of it except that he was not afraid of India anymore. He was anxious about what he had discovered in himself, but he did not want to look any deeper. He didn’t want to feel ashamed for something that he regarded as a kind of victory.

Someone—Miss Bhatia?—was passing him a dish of curried potato. He scooped some onto his plate. Three days ago he would have refused it. He passed the dish to Shah.

“I am not taking potato,” Shah said.

“Allergic?”

“They are having germs,” Shah said. “Also fungus. And little growths.”

“Afraid of getting sick?”

“Oh, no. As I mentioned to you, I am Jain. We do not kill.”

“You mean”—and Dwight began to smile—“you’re trying to avoid killing the germs?”

“That is correct.”

“And the fungus in the potatoes?”

“I will take some of nuts and pulses,” Shah said. And turning to Mr. Desai, “Shall we now discuss payment schedule?”

That was the second, the transformative trip. He left that night, or rather at two the next morning, a changed man. Or was he changed? Perhaps these impulses had always slumbered in him and now India had wakened them, allowing him to act.

“I can’t wait to come back,” he told Shah, who was pleased.

How shocked Shah would have been if he had explained why, and described his encounters—the dancer Sumitra, the waif Indru. He could not stop thinking about them, solitary Indru most of all. The whole of India looked different to him now, brighter, livelier. But more, he was himself changed. I am a different man here, he thought, as the plane roared down the runway and lifted above the billion lights of Mumbai. I want to go back and be that man again.

His fears were gone, he was a new man, he was happier than he could remember. The image of the Gateway of India came to him, and he thought, I have passed through it.

Back in Boston, at his desk, the partners stopped in, to convey their routine greetings, and the repeated note was that they admired him for having gone to India, regarded him as a real traveler and risk taker, gave him credit for enduring the discomfort, talked only of illness and misery, and said he was a kind of hero. All the senior partners congratulated him on the deals he’d done—such simple things, if only they knew. He could have said that Indians were hungry and they helped him because they were helping themselves.

On the first trip, and for part of the second, he had seen India as a hostile, thronged, and poisoned land where a riot might break out at any moment, triggered by the slightest event, the simplest word, the sight of an American. And he would be overwhelmed by an advancing tide of boisterous humans, rising and drowning him amid their angry bodies.

Did you get sick?

India was germ-laden. Sheely had ended up dehydrated and confined to his hotel room with an IV drip in his arm, and he swore he would never go back to that food and that filth.

Dwight too had been anxious. That was why he needed Shah. But giving Shah all that responsibility had released Dwight from the tedium of negotiating the outsourcing deals. Shah had the respect of the businessmen, he could handle them, and Dwight’s silences had been taken to be enigmatic and knowing. Not talking too much, indeed hardly talking at all, had been a good thing. His silences made him seem powerful. How could he explain that to his talkative and bullying partners?

He had feared and hated India. He had gone nonetheless because as a young, recently divorced man with no children he had been the logical choice. He had said, “I’ll hold my nose.”

On the first trip, he had not eaten Indian food, not gone out at night; he had seen the deals to their conclusion and then ached to be home. He had been welcomed home as though he had been in the jungle, returned from the ends of the earth, escaped the savages, the terrorists, a war zone. India represented everything negative—chaos and night. And so on his return from this second visit he understood what the partners were saying; he had once said them himself.

“Human life means nothing to those people,” Sheely had said. And because he’d been to India—and gotten sick—his word was taken to be the truth.

“It’s teeming, right?” Kohut asked. “I saw a program about it on the Discovery Channel.”

Ralph Picard, whose area was copyright infringement, said, “I’ve got to hand it to you, Dwight. I could never do anything like that.”

Читать дальше