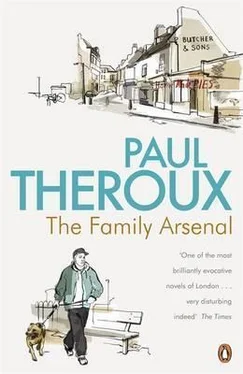

Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Family Arsenal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Family Arsenal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Family Arsenal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Family Arsenal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Family Arsenal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Lorna?’

He switched on the light and saw her cowering half-way down the hall, preparing to run upstairs. He almost recoiled at the sight of her, and she seemed not to recognize him — she registered slow fear, the negligent despair of someone wounded or doomed. And she was wounded. Her face was bruised, her blouse torn, and there were scratches on her neck. She watched him with swollen eyes as he rushed forward and took her in his arms. He could feel her frailty, her heart pumping against his chest.

‘What happened?’

‘They was here — oh, God, I thought they got you too.’ She sobbed and then said, ‘I didn’t tell them anything!’

‘Love, love,’ said Hood, and heard the child cry out in an upper room.

20

The face was a success: even the dog barked at her, and McGravy was taken in for a few bewildered seconds. She had spent the morning at the mirror working on her eyes — it was too easy to wear sunglasses, and down there sunglasses in this dreary weather would attract as much attention as a full frontal. The headscarf and plastic boots were her greatest concession, since her first thought was to go as a man. She knew she could bring it off, but how to explain it? A woman, then, but anonymous. The skin had to have a pale crêpy texture and around the eyes a wrinkled suggestion of neglect and premature aging, with dull green mascara on the lids. It took her an hour to get the right crude stripe. She laboured with care for the effect and finally achieved it in exasperation, realizing afterwards that what she wanted most in her make-up that day was a look of hurry. A woman went out in the morning to shop, but no matter how rushed she was she did her eyes. She aimed at the haste and pretty fatigue of the housewife with a few lurid strokes of eye-liner. Instead of lipstick she practised her bite, clamping her jaw a fraction off-centre to convey, in a slightly crooked grin, that her teeth didn’t quite fit. Then she put on her boots and scarf and an old coat, seeing her Poldy had japped in his cowardly dance of aggression, diving at her and swivelling his hind end sideways until he sniffed her and whimpered into silence.

McGravy said, ‘Don’t tell me. Let me guess —’

‘I’m in a rush,’ she said, rummaging in the trunk for the right handbag and selecting one in imitation leather with a broken buckle.

‘Of course, you’re taking the bus — Mother Courage doesn’t take taxis.’

‘I’m not Mother Courage,’ she said. ‘I’m invisible.’

‘Poldy doesn’t think so.’ But the dog had stopped barking. He was circling her cautiously, sniffing at her boots.

‘And I’m not taking the bus,’ she said, fixing her bite and crushing the handbag under her arm. ‘I’m walking.’

She slipped out the back door and hurried down Blackheath Hill to where it dipped at the lights. Then she was only following signs and the map she’d memorized. She had never walked here, and it was odd, for once she plunged down from Blackheath, walking west to Deptford, the light altered — filtered by a haze of smoke it became glaucous — and it was colder and noisy and the air seemed to contain flying solids.

But she had succeeded in her disguise, and the novelty of being invisible cheered her. She celebrated the feeling. There had been a time, before her political conversion, when the thought of going unrecognized would have depressed and angered her. Then, she required to be seen — not for herself, a compliment to her fame, but because she believed from the moment she had become an actress that the role and the person playing it were inseparable. An actress did not become another person in studying a part: the part slumbered in her, the character — not only Alison and Cicely, but Juliet and Cleopatra — was a layer in her personality like a stripe in a cake. Once she had been asked, after a hugely successful Sixties revival of the Osborne play she had taken on tour, how she had done the part so well. She replied, ‘But I am Alison.’ She was Paulina, Lady Macbeth, Blanche Dubois, and all of Ibsen’s heroines. They were aspects of herself, but more than that their words too were hers. Acting for her was a kind of brilliant improvisation; she gave language life, she reinvented a playwright each time she performed. There was nothing she hated more than the proprietorial way a writer or director regarded the text — they wanted to reduce actors to dummies and conceived the theatre as a glorified puppet show (it was this notion, and more, that made her want to ban Punch and Judy shows — her first political gesture).

Acting was liberation. The theatre had shown her what possibilities people had — it was her political education. Everyone acted, but the choice of roles was always limited by social class, so the labourer never knew how he could play a union leader. True freedom, the triumph of political struggle, was this chance for people to choose any role. It was more than a romantic metaphor — she knew it was a fact. That old man, Mister Punch, leaving The Red Lion at the far end of Deptford Bridge did not know how easily he had been cheated; in a fairer world he would have power. That took acting skill, but there were no great actors, there were only free men.

And unseen, part of the thin crowd, she was free today, stamping in her old coat and faded scarf in the High Road, biting to make her face unfamiliar. This was political proof, not simple deceit, but evidence that the woman she was this grey afternoon was unalterable in a capitalist system. Freer, the woman she mimicked would be a heroine. The mimicry was easily mastered, and though once she had neded attention, now, the very absence of it encouraged her. She could be anyone; she was no one; she could walk through walls.

Deptford — especially those angular cranes and chimneys, the low narrow brick houses, the windowless warehouses — reminded her of Rotterdam. She remembered the errand as one of her most demanding roles, though she savoured it with a trace of regret: it had been robbed of completion. In the end it had failed, and yet nothing she had ever done had so satisfied her, no stage part could compare with it. It was all excitement, the smoky jangling train to Harwich, the Channel crossing that night in early summer, and then the brief electric train past the allotments on the canal to the neat station in that cheerless port. Passing through British immigration, looking the officer squarely in the eye, handing over the American passport — all of it was an achievement greater than her Stratford season. And there was that odd business with her cabin in the Koningin Juliana : she had been assigned a four-berth cabin but she had counted on privacy and had seen the rucksacks and stuffed bags of the other travellers and panicked. She hated the thought of being forced to sleep on this little shelf in a cupboard with three others. She had demanded a single cabin. ‘For your sole use,’ the Purser had said, handing her a new coupon in grudging annoyance and suspicion, believing her to be preparing a corner for a pickup. But she had gone back and sat up the whole night in the four-berth cabin with the hitch-hikers, smoking pot and haranguing them about Trotsky, and in the end she never used the expensive single cabin except to wash her face and check her disguise. She saw how the preposterous expense of the two cabins had shown her in safety how she only needed one; and she laughed at the money it was costing her to learn poverty.

Then there was Greenstain — only an Arab would mis-spell his own alias — with large pale eyes and a fish’s lips, who had met her in the warehouse and touched her as he spoke, as if tracing out the words on her arm. His staring made him seem cross-eyed, and his lemon-shaped face, unnaturally smooth, frightened her. He had the infuriating manner that dull leering men occasionally practised on her — repeating what she had said and giving it a salacious twang. ‘What have you got for me?’ she said, and Greenstain wet his lips and replied, ‘What have you got for me?’ Then she said, ‘Show me,’ and he said the same, twisting it to make it the gross appeal in a stupid courtship. He had spit in the corners of his mouth and wouldn’t stop touching her arm. She was afraid, he was scaring her intentionally, and it was much worse than deceiving the immigration officers — even the friendly Dutch ones with their ropes of silver braid — because she was alone with Greenstain in that empty warehouse. He was pretending to be sly and he made her understand, using his pale eyes and greedy mouth, that he could kill her and take the money he knew she was carrying. At last, he led her to a corner of the warehouse and showed her the trunks. He kicked one open and took out a gun and pointed it at her and cackled, working his jaws like a barracuda. She paid — the first of the proceeds from Tea for Three, Greenstain counted the money, then examined each note, making her wait while he checked the bundle for forgeries. He gave her an absurd handwritten receipt with the name of the London agent and took her outside. It was dark; the canal lapped against the quayside. Greenstain belched, then embraced her and she looked up and in panic memorized a word painted on the warehouse, Maatschappij, and wondered how it was pronounced. Grenstain ran his hands down her body and then jumped away. For a moment she thought he might shout. She saw him nod; he broke into gaggling laughter. ‘A girl!’ he cried. ‘You are a girl!’ He pushed her lightly. Uninterested sexually, he became almost kind, and later on the way back to The Hook he pointed out the war-time bunkers and, in a settlement of houses, a still solitary windmill.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Family Arsenal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.