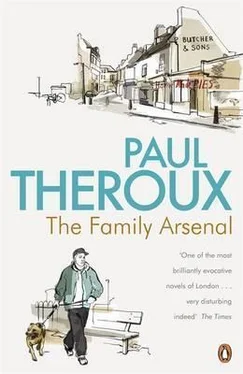

Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Family Arsenal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Family Arsenal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Family Arsenal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Family Arsenal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Family Arsenal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘No.’ But Hood peered at the painting.

‘Maybe not,’ said Murf. ‘He’s posh like you, but not only that. Yeah, I think he does. Straight.’

Hood said suddenly, ‘What do you want, Murf?’

‘Nothing.’

Nuffink. ‘I want to give you something, squire. Anything.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Murf carefully. ‘But there’s one thing.’

‘Name it.’

‘Just don’t,’ Murf began and caught his lips again with his fingers. ‘Just don’t laugh at me.’

Hood waited for more. Was this a warning, a condition to prepare him for the wish — or the wish itself? Murf fidgeted and said no more, and Hood saw that it was all he wanted, to be free of ridicule. The woman’s laughter had wounded him and made her his enemy. Hood said, ‘Okay.’

‘Me mates don’t laugh at me.’

‘Then we’ll be mates.’

Murf grinned, filling his cheeks, as if he had food in his mouth; and he put out his hand, offering it as an equal. He said, ‘Shake.’

Hood reached up and wrung his hand — Murf’s palm was damp with nervousness — and he said, ‘Now I’m going to hit the sack.’

Murf hesitated. ‘Mayo didn’t show.’

‘No,’ said Hood. ‘Maybe it’s something big.’

‘Yeah.’ Murf sniggered. Something big : now it was a private joke they could both share. ‘Are you going to tell her about the old girl?’

‘Do you want me to?’

‘She’ll laugh at me.’

‘I can say I was here the whole time.’

‘Right.’ Murf brought up another gobbling grin. ‘And she’s bending your ear, this old girl. Then you’re out of the room, you’re having a wash. You don’t know nothing. Then she goes sneaking upstairs. You hear this fucking laugh of hers.’

‘And I caught the bitch in this room.’

‘Beautyful.’

‘That’s what I’ll tell her then.’

Murf said, ‘Goodnight, mate.’

Mayo did not arrive until the next morning, and showing her face at that early hour, with an over-brisk apology but no explanation for her lateness, and yet with a guilty pallor made of smugness and fatigue — the satisfied smile and yawn — she had the cagey adulterous look of a woman returning to her husband and children after spending the night with her lover. Romance: if not actual, then a metaphor, since she had always treated her political involvement like an affair, her energy hinting at brief infatuation.

Brodie stirred her bowl of cornflakes with a spoon and said, ‘There’s no more milk.’

‘I’ve had my breakfast,’ said Mayo. ‘I was up hours ago. I’ll just have a coffee. Any post?’

‘A letter from the National Gallery,’ said Hood. ‘They want their picture back.’

‘That’s not funny.’

Murf looked at Hood and laughed.

‘Look, sugar,’ said Hood, touching Brodie on the arm, ‘why don’t you and Murf do the dishes. I’ve got a bone to pick with the klepto.’

‘I always have to do the dishes,’ said Brodie, complaining.

Murf rose and began gathering empty cups. ‘You heard what he said.’

‘Go to it, squire.’

In the parlour, Mayo said, ‘I’m exhausted.’ Hood didn’t react. ‘The meeting went on for hours.’

‘The offensive,’ said Hood lightly, as if repeating a familiar joke.

‘That was part of it,’ she said. ‘And we expelled someone.’

‘Do I know him?’

‘Her,’ said Mayo. ‘I doubt it.’

‘We had a visitor yesterday.’

‘Not the police,’ Mayo held her breath.

‘No. A friend of Brodie‘s.’

‘I didn’t think she had any friends.’

‘You’d be surprised,’ said Hood. ‘It was a lady — in the technical sense.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘I’ll tell you in a minute. But first I want you to tell me something. Where exactly did you get your picture?’

‘The self-portrait? Highgate House — why?’

‘Who lives there?’

‘No one lives there, you fool. It’s a museum.’

‘That’s the first I’ve heard of it. I thought it was a private house. I imagined you sneaking through the window, tip-toeing down the corridors — the folks snoring in their beds. I thought it was pretty cool. She’s a gutsy chick, I thought. But, for Christ’s sake, it was a museum. So it wasn’t such a big deal after all, was it?’

‘There was a burglar alarm,’ she said. ‘There were risks. What are you trying to say?’

‘Just this. You gave me the impression you knocked off a private house — and all you really did was waltz into a museum and rip off a picture. If it had been a private house you might have gotten somewhere, and if you’d chosen the right one you’d have scored in spades — you’d have had them screaming their heads off. But you’re a genius. You went for a museum and came out with one picture — you could have taken a dozen!’

‘What’s wrong with a museum?’

‘Museums don’t have money. They don’t pay ransoms, no one lives in them, they’re empty.’ He sighed and said, ‘How’d you happen to settle on Highgate House?’

‘I told you all this at Ward’s — that first day.’

‘You were drunk. You didn’t have a plan. All you talked about was a picture.’

‘Yes, and I knew where it was.’

‘You sussed it out?’

‘No,’ she said, ‘my parents used to take me there.’

She stated it as a simple fact; but it was a revelation. It was the most she had ever told him about herself, and it was nearly all he needed to know.

My parents used to take me there. He knew her parents, he saw them on a misty Sunday in winter guiding their daughter to the museum, the mother apart, the doting father holding the girl’s hand. They had planned it carefully; they knew they were paying a high compliment to the little girl’s intelligence in the family outing — part of her education, while the rest of her school friends idled at the zoo. A restful, uplifting interlude, strolling among the masterpieces. Privilege. And he saw the daughter, a spoiled child, small for her age, but bright, alert, in kneesocks and necktie, noticing details her parents missed — that Bosch cripple in his leather vest, the thread of piss issuing from the bow-legged man in the Brueghel, the Turner thundercloud and tidewrack of sea-monster’s jaws, the tiger launching itself from the margin of the Indian engraving. Look, dear, an angel. And finally the attentive parents brought her to the Flemish self-portrait and urged her to admire the tall man in black: What do you see through that window? Later, they bought postcards and chatted about them over tea; but the parents never knew how that afternoon they had inspired the girl — made her see the value of art even if she could not see its beauty; how the gentle stress that particular day, the origin of all her careless romance, had made that little girl into a thief.

Hood knew her parents, he saw them, because he could see his own. The same encouragement in a different museum, a different light: a Minoan snake-goddess had marked his eye. They had been taught to respect art, so thievery mattered; and the parents’ legacy was this taste, a hesitation. Only Brodie and Murf acted without hesitation. They could destroy easily because they had never seen what creation was — they did not know enough to be guilty; but Mayo, and he, knew too much to be innocent.

Mayo saw the strain of memory on his face. She said, ‘What’s wrong?’

‘You blew it. You’re a flop.’

He told her the version he had promised Murf, and what Lady Arrow had said. Mayo understood immediately, quicker than Hood himself had. She closed her eyes and he could see she was relieved — as he had been, but perhaps for a different reason: he had never wanted to lose the picture and she had worried about jail.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Family Arsenal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.