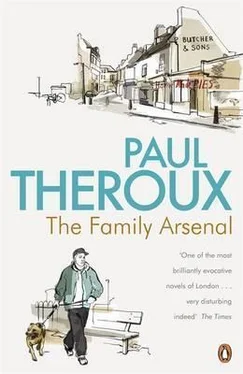

Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Family Arsenal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Family Arsenal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Family Arsenal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Family Arsenal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Family Arsenal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Sometimes I don’t think I can bear it a minute more. It’s such a fag, and there’s a matinée on Wednesdays. I don’t know how I do it — I have to suck sweets to keep awake. It’s dreadful.’

‘You seemed to be enjoying yourself,’ said Hood.

‘I am an actress,’ said Araba.

‘Yes, the play was very interesting,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘Interesting?’ she said, using her voice to doubt it. ‘No one’s ever said it was that.’ She addressed Hood. ‘What did you think of it?’

‘I’m not a very good judge of plays,’ said Hood. ‘The audience seemed to like it, though.’

‘I don’t want to talk about them,’ said Araba.

‘We’ve heard your good news,’ said Mr Gawber. ‘About Peter Pan .’

‘It was the boy-girl part in this thing that did it. It’s just a gimmick. Peter Pan is a big play — I wonder if you know how big? I hate some of the audiences, so many queers think of it as their own vehicle. I’m only doing it for the kids. They understand it — they go out hating their parents. That’s how it should be. God, I love acting for kids! They really appreciate what you do for them. They don’t have any hang-ups. They’re terrible critics — if they think it’s a lot of old rope they say so; if they feel like screaming, they scream. I love that.’

They were seated near the door, drinking half pints of beer, and from time to time young men with blow-waves and backcombed hair, and girls peeking from beneath wide-brimmed hats, had called out ‘Araba’ and ‘Darling’. Araba had smiled and gone on talking about acting for children (‘There’s no ego-trip involved — they’re not interested in stars and personalities’). Now they were approached by a short woman pushing through the crowd, holding a small dog Hood had first taken for a handbag — it was square and still, with tight curls. The woman had freckles on her thin face and chewed an empty cigarette holder. Under this veil of freckles the woman — who was no larger than a child — had the sly mocking face of an old elf. But there was about her size and the way she was dressed a neatness that was sharp and unconcealing: the small body showed through the green coat as the slyness had through the freckles. She said in a high voice, ‘Poldy wants to say hello.’ She spoke to the dog: ‘Say hello to Araba, my dear. Get on with it — don’t just sit there.’

‘McGravy, I’d like you to meet one of my dearest friends, Ralph Gawber.’

Mr Gawber said, ‘Very pleased to meet you. This is Mister Hood.’

‘Mister Hood is not a very good judge of plays,’ said Araba.

McGravy said, ‘Send him to Tea for Three .’

‘I just saw it,’ said Hood.

‘What’s the verdict?’ said McGravy.

Hood considered for a moment, then said, ‘It’s got a lot of food in it, hasn’t it?’

‘It’s all about food,’ said McGravy.

‘And that was one damned hungry audience. I could see them licking their chops.’

‘Everyone’s starving nowadays,’ said McGravy, looking uncertainly at Hood, who was smirking. ‘It’ll get worse.’

‘I sometimes think that,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘It’s the system,’ said Araba, and her eyes flashed. ‘All this deception. All these hangmen. And these leeches — bleeding people to death. It makes me want to throw up.’

‘Parasites,’ said McGravy, cuddling her dog until he growled his affection. ‘Well, they’ll get what they deserve.’

‘I think that needs saying,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘Bloodsuckers,’ said Araba. ‘It’s a Punch and Judy show, but it can’t go on like this.’

‘I couldn’t agree with you more,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘It really is rotten,’ said McGravy. ‘It’s like a boil that needs lancing — then it’ll all come gushing out, all the corruption and lies.’

‘I’m so glad you said that,’ said Mr Gawber. He leaned forward, encouraged. Two hours of sleep in the theatre had rested him. He said spiritedly, ‘No, the workers have had it all their own way since the War, but now they’re simply malingering, holding industry to ransom. A period of recession wouldn’t be a bad thing. A crash might even be better — a dose of salts. I agree unemployment’s a bitter pill, but the workers have to realize —’

‘Who’s talking about workers?’ said McGravy sharply in her high child’s voice.

‘Let him finish, sister.’

‘Whose side are you on?’ McGravy demanded.

Mr Gawber said, ‘Aren’t you talking about workers?’

‘No,’ said Araba, patting Mr Gawber’s hand. ‘We’re talking about the power structure, my darling.’

‘But the unions,’ said Mr Gawber. ‘With all respect, there’s your power structure, surely?’

‘The union leaders are in league with the government,’ said McGravy. ‘It’s a plot —’

‘Dry up,’ said Hood.

‘I had no idea,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘Let’s talk about the play,’ said Hood.

‘I’d rather not,’ said Araba.

‘Wait, Araba. Perhaps he has some insight he wants to share with us.’

‘My insight,’ said Hood, ‘is I think it’s the biggest waste of time since parchesi.’ He smiled. ‘A load of crap.’

‘Come now,’ said Mr Gawber. He thought it tactless of Hood to say it, but all the same agreed and felt a greater fondness for him.

‘It made him mad,’ said Araba.

‘It’s supposed to make him mad,’ said McGravy.

‘But it is a wank,’ said Araba.

‘If only it was,’ said Hood. ‘I was sitting there and saying to myself, “What’s the point?” ’

‘If only he knew,’ said McGravy, grinning at Araba.

‘What don’t I know?’

‘Several things,’ said Araba. ‘But the first one is that McGravy wrote it.’

‘Oh, my,’ said Mr Gawber. ‘You have put your foot in it.’

McGravy stroked her dog and let him nuzzle her. She turned to Hood. ‘You were saying?’

‘Nothing,’ said Hood.

‘Go on, I’m rather enjoying your embarrassment.’

‘It’s not embarrassment, sister, and if you think I’m worried about hurting your feelings, forget it. If you wrote that play you must be so insensitive you’re bulletproof.’

‘I wish I were,’ said Araba.

‘Who are you anyway?’ said McGravy.

‘Just part of the audience,’ said Hood.

‘Drink up, please,’ said a man in a splashed smock, collecting empty glasses from the table.

‘I have a train to catch,’ said Mr Gawber.

‘Let’s get a coffee at Covent Garden,’ said Araba to Mr Gawber. ‘Then we’ll let you go home.’

They trooped up to Covent Garden, turning left at the top of Catherine Street, where long-bodied trucks were trying to back into fruit-stalls at the market. There were men signalling directions with gloved hands, and behind them stacks of crates and displays of vegetables. In spite of the trucks it had for Hood the air of a bazaar — the dark shine of the cobblestones, the littered gutters and piles of decaying fruit; the men jogging with boxes on their heads and others bent almost double under the weight of sacks. Mr Gawber thought he saw the two men with the laden prams he’d seen earlier that day in the stairwell below Waterloo Bridge; he remembered the warning, ARSENAL RULE, and then actually saw it, splashed on the arches of Covent Garden Market. Over by the tea stall gaunt men stood inhaling the steam from cups of tea.

‘I love it here,’ said Araba, whirling her cape open, performing.

The men saw her and grinned. McGravy’s dog, lively for the first time, yapped at the tea drinkers. Mr Gawber was uneasy: the men were wretched and dangerous-looking; he wanted to go home. But Araba had bought four cups of coffee from the man in the stall — he had tattoos, and a torn singlet, and a hat folded from a sheet of newspaper — and she was handing them out. Mr Gawber kicked the squashed fruit from his shoes.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Family Arsenal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.