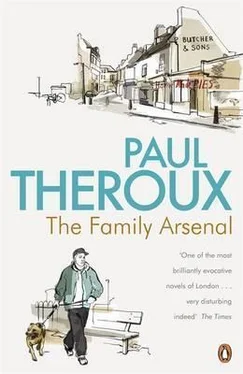

Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Family Arsenal» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Family Arsenal

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Family Arsenal: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Family Arsenal»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Family Arsenal — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Family Arsenal», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Still Norah snored, and dayspring — who said that? — dayspring was mishandled. The traffic began on Catford Hill, and on Volta Road the clank of the bottles in the milk float, the grinding front gates, the plunk of the letter-slot. And the September sun — for once he was glad dawn came early. He went down, made tea and brought Norah a cup. She slept as if she had been coshed, bludgeoned there on her half of the raft: her mouth was open and she sprawled face-up, ventilating her sinuses with rattling snores. He woke her gently. She blinked and smacked her lips and said, ‘I had a dreadful night.’

He was silent at breakfast, though he allowed himself a glance at the crossword, the letters, the obituaries. An item on the front page shocked him.

‘You know what that means, don’t you?’ Norah said.

… unclothed and partly decomposed body , he’d seen. Why did they print such things, and which ghouls read them? He folded the paper and said, ‘What’s that, my dear?’

‘I won’t be able to go to the play.’

Indecent — worse: hideous. He saw the body and tasted it on his toast. ‘What play is that?’

‘Tea for Three,’ said Norah. ‘I was so looking forward to it.’

That too? How trivial and sour the title seemed over breakfast. He said, ‘I’d completely forgotten about it. You might be feeling better tonight. I must say, I’m feeling a bit off. That’s enough breakfast for me.’

‘I won’t enjoy it. It won’t be the same.’

‘Then I shall cancel the tickets.’

‘You can’t do that. It’s a gift — Miss Nightwing will be terribly upset. She was counting on us to go.’

‘But what will I do with the extra ticket?’

‘You can take someone from the office. Miss French.’

‘The inevitable Miss French.’

‘One of the clerks. Mr Thornquist. They’d be glad of a chance. And you can tell me all about it.’

‘Are you sure you can’t go?’

‘Rafie, I feel ghastly. I have this rotten feeling in my stomach —’

She described it with disgusting care, checking Mr Gawber’s reverie. Sick people knew their ailments so thoroughly. He clucked and tilted his head in concern; he listened and felt a vengeful glee rising to his ears. He was ashamed, but even that did not diminish the pleasure of hearing her drone on about her stomach. She had deprived him of a night’s sleep.

He promised to get tickets for another play: they’d see Peter Pan at Christmas. A penance — he would have to sit through two plays for her gastric flu. And she said she couldn’t face making his lunch. So the crush of a noon-time pub as well, elbows and soapy beer and the yakking of loud clerks in the smoke. The catastrophe would finish them, but he wanted it soon. Sometimes he wished there was a chain he could pull to start the landslip quickly.

‘Why are you smiling?’

‘I’m not smiling.’ Was he? What did that mean? ‘I’ve got something stuck in my tooth.’

‘Is there anything in the paper?’

‘No.’

He left for work, glad to be free of the house, the stale air of the sickroom. He crossed the frontier of the Thames and was restored by the fresh air in the solider part of the city. He chose the Embankment route to the Aldwych, walking behind the Savoy, pausing at the statue of Arthur Sullivan where the heartbreaking nude sorrowed on the plinth; then along the neat paths to the stairwell below Waterloo Bridge. The graffiti howled from the walls, unpronounceable madness and the threat that had become so frequent: ARSENAL RULE. Two homeless old men bumped their belongings down the stairs in prams, like demon nannies with infants smothered under teapots and ragged clothes. The men and their prams were secured with lengths of string. It was an omen: soon the whole population would be shuffling behind laden prams, crying woe.

His reflection was interrupted by the tickets he had been lumbered with. Who to take?

In the course of the morning he worked through a short-list. The receptionist yawned at him. Not her, an any case: people would talk. The messenger, Old Monty? He had a room in a men’s hostel in Kennington. A clean man, he smelled of carbolic soap and was always speaking to Mr Gawber of weevils and black beetles and how the other men never changed their shirts, and how they left the bathroom in a mess. He had been in an army band: Aldershot, Indian camps, Rangoon. ‘I should have stuck with the clarinet,’ Monty said. He’d enjoy a play. Mr Gawber risked the question, but Monty said, ‘I always do my washing on Thursdays.’ Rodney, the stockroom boy? Rodney brought fresh pencils at eleven o’clock, but with a clatter that hurt his teeth. In such a careless gesture he saw the boy would resign one day soon. It was the pattern: they became clumsy, then they quit. Not Rodney.

‘Ask Ralph — can’t you see I’m busy?’ said Thornquist irritably waving a secretary away.

And not Thonky.

Sadly, the inevitable Miss French. But she said, when he approached her, ‘I hope you’re not going to ask me if those letters are typed. They’re all here, just as you gave them to me. I couldn’t read your writing.’

He was proud of his handwriting. It was a good uniform hand, sacrificing loops for a workmanlike clarity. The woman was lying. Not her.

He picked up the phone and dialled. There was a buzz, a jumble of clicks, then, ‘— but if I sell now at thirty-three I’ll be out of pocket to the tune of four thousand.’

‘By tomorrow morning it will be five thousand,’ said another voice.

‘Sell now,’ said Mr Gawber, and hung up.

He took out the business card and confirmed the Kingsway address, found the entrance and just inside on the wall the name Rackstraw’s on a column of varnished boards. He ran up the steps three at a time and met the receptionist who, with headphones at rest on her neck, was reading a magazine.

‘Mister Gawber, please.’

The girl looked up from her magazine. ‘Do you have an appointment?’

‘No.’

‘You’ll have to take a seat.’

‘I’ll stand.’ He saw the girl return to her magazine. Then he said, ‘You can tell him I’m here.’

‘There’s someone ahead of you.’

‘I don’t see anyone, sweetheart.’

‘He’s got an appointment. He’s not here yet.’ Now the girl was not reading, but simply holding her elbows out and flipping pages to avoid facing another question.

‘I wish you’d do something. I’m in a hurry.’

‘I’m doing everything I can.’ She didn’t look up. ‘This is a busy office. Appointments only. That’s the rule.’ She turned the pages quickly and shook her head. ‘I don’t make the rules.’

An elderly man in a dark blue messenger’s uniform came through the outer door. He stopped at the desk and made a swift reflex with his heels.

‘That packet’s from Mister Thornquist,’ said the girl crossly. ‘It was supposed to be delivered an hour ago to the City. By hand.’

‘Sorry,’ said the man. ‘I was doing the post.’

‘The post doesn’t take two hours, Monty.’

‘Parcels,’ said the man. ‘They wanted weighing.’

‘Listen, Monty, that packet’s been sitting there —’

‘Back up,’ said Hood striding over to the girl. She was startled. He said, ‘Why are you talking to him that way?’

‘I’m sorry but —’

‘Cut it out. Don’t use that tone with him.’

The man stared.

Hood said, ‘Don’t let her talk to you that way.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said the man. ‘I was just going to say that myself.’

Hood turned again to the girl. ‘If I catch you giving him any lip I’ll come back here and slap your ass.’

He walked past her to the office door.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Family Arsenal» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Family Arsenal» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.