“I like this one,” I said.

“She’s wearing socks,” Chicky said.

“She looks more naked that way.”

“You’re nuts.”

Chicky found the cover, all in color, Naturist Monthly, two women playing tennis, seen from the rear, a nudist magazine. We pieced some pages back together and saw naked people putting golf balls on a miniature-golf course, others playing Ping-Pong, some swimming, and oddest of all, a family eating dinner at an outdoor picnic table, Dad, Mom, and two little flat-chested girls. Mom was smiling: droopy tits and holding a forkful of droopy spaghetti.

“You can’t see the guy’s wang,” Chicky said, “but lookit.”

Naked children frolicking in shallow water with naked parents, a whole bare-assed family. And even though one of the teenage girls was being splashed I could see her breasts and a tuft of hair between her legs.

“I bet she’s not a virgin,” Walter said. And then, grunting, “I’ve got a raging bonah.”

“Give him some saltpeter,” I said.

That was the remedy we had heard about, to prevent you from getting a hard-on. People said that in some schools the teachers mixed it with the food, to keep the kids out of trouble.

We trawled with the branches, hoping for more thrown-away pages. There were certain secluded places at the edge of the woods or near the ponds, where cars could park, where we found these torn-up or discarded magazines. They were always damaged; we had no idea where anyone could buy them. Without being able to explain it, we knew that men took them here, as part of a ritual, a private vice, to look at the forbidden pictures and then destroy the evidence.

And we did the same, piecing the wet pages together, and gloating over them, and then, feeling self-conscious, we scattered them and kicked them aside and walked on.

At the far margin of the pond, there was another parking place, another barrier, more litter, broken beer bottles and paper.

“It wasn't here,” Walter said.

We knew what he meant. We were more relaxed, kicking the trash, for sometimes there were coins in the cinders.

“Lookit. A Trojan,” Chicky said.

A rubber ring, partly unrolled, thin balloon skin protruding, lay lighdy on the ground.

“Never been used,” Chicky said. He poked it with his gun barrel. “No jism in it. All dry.”

“What do you figure he did with it?” Walter said. “Huh, Andy? Tell us the story.”

“He goes, ‘Open your legs.’ She goes, ‘Use a rubber.’ He takes it out but she’s so hot and bothered he doesn’t have time to put it on his dong. Her legs are open so wide he can see up her hole and into her tonsils. He throws the rubber out the window and bangs her.”

Chicky was giggling as he said, “What else?”

“She’s saying, ‘Farther in, farther in!’ He goes, ‘I’m not Father In, I’m Father O’Brien and I’m doing the best I can.’ Now she’s knocked up.”

“I like the way you tell stories,” Chicky said, as Walter, holding up his Remington, showed us a rubber dangling, suspended from the nipple on the front sight. “It’s used,” he said.

The slimy smooth gray-white rubber reminded me of naked bodies, hairless women's skin, and penises.

“Prophylactic,” I said, trying out the word that was on the Trojan wrapper.

“You can get a wicked disease from that.”

Walter flopped it onto the ground and fired his gun into it, and at the same time the three of us looked around, hearing the gunshot echo, blunted by the pond.

“Let’s go,” I said, fearing that someone might have heard.

As we walked quickly away, Chicky said, “I know this guy who got a pack of his brother’s Trojans and stuck a pin through each one. So that when his brother banged his girlfriend a little bit of sperm leaked through.”

We tried to picture it. A little bit of sperm leaked through did not seem very risky, not enough to make a baby. You needed a lot of sperm for that, and in my mind some sperm represented arms, and some legs, and more would make the baby’s body and head.

We left the bridle path and crouched, ducking through the budded bushes, traversing the hill. No one could see us, and as always when we were sneaking through the woods like this we were careful not to step on any twigs. We trod on the balls of our feet, “sure-footed,” as though in moccasins, like the Indians we saw in movies who were indistinguishable from the bushes and the mottled light of the forest.

“Heads up,” I said, hearing muffled hoofbeats, a lovely sound, because it was not a gallop but a slow tramping gait, the hooves crushing and grinding the cinders on the bridle path. The sound made us feel more than ever like Indians. “It’s a mounted cop.”

He rode upright in the saddle like a sheriff in a cowboy movie, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and shiny black boots, a big black holster at his waist on a wide belt. We pressed ourselves against the ground, like Indians in the same movie, watching him, feeling anxious pleasure that he did not see us as he passed, and when he was gone, just the distant sound of hooves, intense excitement.

“We could have told him about the homo.”

“He wouldn't have believed us.”

“He'd take our guns away,” Chicky said. “He’d tell our parents.”

Another mile onward, walking along the margin of the bridle path, we came to a clearing, the meadow of the Sheepfold, some scorched stone fireplaces and picnic tables and stumps to sit on. The place was empty this cold afternoon: all ours. We gathered wood and started a fire, warmed our hands, piled on more wood, and I whittled a stick to roast the hot dogs.

Walter said, “Those things have shit in them, real pieces of shit.”

“You’re just saying that because you don’t eat meat,” Chicky said. “Because of your religion.”

He unpacked some Italian sausages, bright red meat and pepper, speckled white with fat, and held tight with filmy sausage casing that looked like a Trojan. These he penetrated lengthwise with a sharp narrow stick, and held them over the fire, letting them sputter and burst.

“I’m going up for a Cooking merit badge,” Chicky said.

Walter ate a chocolate bar while I burned my hot dog and, trying to toast it, burned the roll I had brought. Chicky nibbled the burned end of one of his sausages, and roasted it some more over the fire.

“It looks like a bonah,” Walter said.

“Hoss cock,” Chicky said.

While we were sitting there, the fire crackling, the smoke blowing around us, three people approached through the meadow, two men and a woman. They were much older than we were, and had the look of being strangers, not just to these woods but maybe to the state.

“What’s the name of this place?” one of the men asked — the taller one, in the sort of thick warm sweater I associated with college students.

“Sheepfold,” I said. “Where are you from?”

“Tufts,” the man said.

Chicky said, “Hey, can I see that pocket book?”

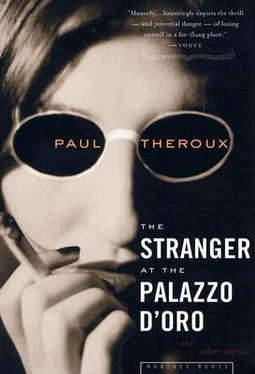

The smaller of the two men, young but balding, wearing a blue windbreaker, was holding a paperback book. On the cover was a crouching woman clutching her head. You couldn’t see much of her, but you knew she was naked. The title was Escape from Fear.

“It’s a psychology book,” the man said.

Chicky snatched at it and almost got a grip, but before he could try again the taller man batted Chicky’s arm, hitting him hard and knocking him off balance. Chicky, too startled to get to his feet, held his elbow where he had banged it on the ground and began to wail — not cry, but howl.

“Hey, you hurt my friend,” Walter said, and I admired him for stepping up to the man who was flanked by two other people.

“I’m sorry,” the man said, looking suddenly worried and regretful. He pulled a pack of gum out of his pocket and gave it to Chicky, who had stopped wailing but was still holding tightly to his elbow.

Читать дальше