"Just listen," he said.

He had wanted to use Irma's men's room, but the radiologist was so intrusive he hurried out. On his way into the one at the International Marketplace, he felt a hard, hot pinch on his bottom, a sharp pain that made him squawk. He turned to see a woman laughing at him, holding her mouth wide open, showing the shiny gray fillings in her teeth, like metallic dentures. She had big beefy arms and broken nails. She mocked him with the fingers she had used to pinch him, holding them like a pair of pliers.

He was fearful inside the men's room. He was fearful leaving it. But even when he was free of the place, he noticed that nearly all the women prowling the Waikiki sidewalks were staring at him.

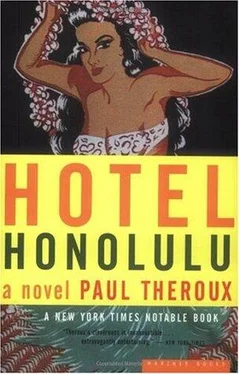

Nestled behind its signature monkeypod tree just two blocks from the beach, Palfrey wrote in his room at the Hotel Honolulu, one of the last family-owned hotels, where brunch is a Honolulu tradition, the Hotel Honolulu is one of Waikiki's best kept secrets.

A secret kept from Palfrey himself, perhaps, for he could go no further. Oppressed by his hotel room, he walked to Ala Moana Beach and felt calm again. His folding chair seemed jammed — sand in the joints of the legs — and as he jerked at it, a woman came over, snatched it, and said, "Let me do that," and popped it open.

"Mahalo," Palfrey said.

The woman said, "Now, how about you do something for me." She touched herself on a lower panel of her bathing suit and licked her lips.

This was down near the orange lifeguard chair at the Magic Island end of the beach. The woman was lined and leathery, purplish from the sun, with salt-stiff hair and salt rime on her too loose bathing suit. Patches of coarse sand clung to her calves and elbows.

When Palfrey said no, the woman swore at him ("It was gross") and swaggered away. At this point, out of desperation, but also thinking it might be a good story idea, Palfrey went to the Hawaii Humane Society at the south end of King Street and announced himself as a member of the American Kennel Association. The lobby reeked of the burning hum of cat shit and the eye- stinging tang of cat piss. Taking a shallow breath, Palfrey asked whether any of their dogs needed walking.

"You know about our Canine Caregivers Outreach Program?" the woman at the counter asked. She had the patient, long-suffering look of a foster mother, and Palfrey was encouraged.

Shortly afterward, a man in overalls brought out a large jittery dog that began barking pointlessly and stumbling with excitement.

"This is Soldier," the man said.

"He's definitely got some Lab in him!" Palfrey cried. He made faces at the excited dog and was thankful for the dog's attention. Palfrey was happy, he felt purposeful. This was something real he could write about: the Canine Outreach Program and also the theme that when he was with a dog, he felt content. He left the building with Soldier, a big black creature with the snout and some of the contours of a Lab's solid head, the big soft nose, the grateful eyes and busy tail. Soldier had a slack tongue and thirstylooking jaws. The dog shook himself on the sidewalk and strained at his leash, glad to be outside and wanting more. Paifrey talked to the dog in the sort of continual flow of affectionate banter that other people might use on a mildly backward and muchloved child who had not yet learned to talk.

Comforted by Soldier, feeling protected, Palfrey returned to Ala Moana. After the dog had had a good run near the tennis courts, Paifrey sat on the sea wall, the dog's snout resting against his knee. He took out his notebook and looked at his opening: Nestled behind its signature monkeypod tree just two blocks from the beach, one of the last family- owned hotels, where brunch is a Honolulu tradition, the Hotel Honolulu is

one of Waikiki's best kept secrets. He doodled and tried to resume, attempting to marry factuality with gaiety. Hearing a burst of human squawking, he looked down the beach and saw some local youths, two boys and a girl, spitting water and yelling "Fuck you, Buddha-head!" at a Japanese man and his small daughter — tourists, probably. Palfrey scratched the dog's belly, watching its eyes grow contented. He was safe with this animal.

Four women passed by that morning, each asking Palfrey the name of the dog and had he taken it through quarantine here? Three of them he ignored. The fourth was prettier than the rest, very pretty in fact. She, too, had a dog in tow, a yellow Lab. Soldier raised his head, and his tongue, which was thick and purple, tumbled out, trailing a string of elongated drool. The woman's dog gave a low growl and got to its feet.

"Miranda," the woman said, cautioning the yellow Lab.

Palfrey smiled at Miranda. The woman reached down to stroke Soldier, though Soldier, too, had his eye on Miranda. His muscly tongue lifted and curled, as though a sign he was taking an interest in the woman.

"Doing some writing?" the woman said.

Palfrey saw the line Nestled behind its signature monkey pod tree just two blocks from the beach and covered the page. "I'm a travel writer," he said, and casually mentioned his name and the title of his monthly column, "A Little Latitude."

"That rings a bell," the woman said. She didn't specify whether she meant his name or the column title. "I'm Dahlia."

Her hand was hard and damp, and white streaks stood out on her forearm. She was fattish, with big soft cheeks and kindly eyes. Her shoulders were freckled from the sun, and her hair was sunstreaked. She wore a loose flower-print dress, open-toed sandals, rings on some of her toes, a tattoo on one knuckle. Free spirit, Palfrey thought.

As Soldier began to poke his snout at Miranda's tail, Miranda crouched slightly and glanced around at the seemingly single-minded animal.

"You're so lucky to be able to write for a living," the woman said.

They were now both looking at the dogs.

Palfrey said, "It's not a job. It's my life."

"I feel that way about my ceramics."

Now he understood her rough hands and the powdery streaks on her arms. Clay, obviously.

"You could write a Travels with Charley-type book."

"My favorite book." He took out his wallet and showed her a snapshot of Queenie.

Now Soldier and Miranda were romping in the grass, chasing each other around the banyan trees. Palfrey recognized the barks: not warnings or fear but yelps of pure excitement. He explained that he had taken Soldier for the day as part of the Canine Caregivers Outreach Program. He could see on her face that Dahlia was moved by his saying this. Perhaps it was her plumpness that caused her to exaggerate her facial expressions? She touched his hand, and he could not keep his own hand still, for her fingertips were coarse and heavy. She believed he was strong. Palfrey didn't say he had felt afraid and lonely and put upon, that he needed the dog for reassurance, that the dog's leash was preventing him, Palfrey, from straying.

Dahlia said that she never went anywhere in Honolulu without Miranda. She said, "I'm fearless when I'm with my dog, because my dog is fearless."

In gratitude, Palfrey extended his hand and touched Dahlia's arm, and when he did so, she reached over and snagged his fingers, saying nothing, for the gesture was unambiguous.

"Almost time for Miranda's supper."

"I wish I had something for Soldier."

The dogs were now rolling in the grass, gnawing at each other.

"I've got something for your dog," the woman said. When she smiled Paifrey could see that she took good care of her teeth, so he knew that health maintenance was a priority for her. "Well groomed" was an expression he did not care for, yet it described an essential habit of sanity and cleanliness. Something grubby in a person, a certain smell, ugly

clothes, even something as simple as a salt-crusted bathing suit, indicated to him an unsoundness of mind.

Читать дальше