Did you see Ms. Ballman in the months before she died?

Did your wife know you were meeting her?

How did she look? Was she still attractive?

Did Ms. Ballman ask you to ask Ms. Homes if she would give her a kidney?

And what did you tell Ms. Ballman?

Did you later tell Ms. Ballman that in fact you had asked Ms. Homes and that she said no?

Did it occur to you that Ms. Homes did not know about Ms. Ballman’s condition, nor did she have a chance to say good-bye?

Did you go to your own personal doctor and inquire about donating a kidney to Ms. Ballman?

Did you tell Ms. Homes that you had done that?

And what would your wife have thought about that — would you have had the surgery without telling her?

Did you know that Ms. Ballman was going to die?

How did you feel when you heard that Ms. Ballman had passed?

And your last phone call with Ms. Homes — several months after Ms. Ballman’s death — how did that go?

How did it end? Did you say, “Call me anytime. Call me in my car. My wife’s not usually in the car”?

Why would Ms. Homes need to call you in the car as opposed to in your home?

Is anyone harming you, confining you, not allowing you to make and receive calls and/or mail?

Are you angry with Ms. Homes?

When Ms. Homes’s New York lawyer called you — the same man who called you to tell you that Ms. Ballman had passed — and asked you for a copy of the DNA test, you told him never to call you again and referred him to your lawyer.

Mr. Glick called your lawyer and was told by your lawyer that the DNA document had been misplaced and that you would not sign an affidavit of paternity.

Did you know that Mr. Smith had misplaced the test results?

Are you concerned that other important documents may have been misplaced or mishandled?

Does it not seem a little too convenient that Ms. Homes is asking for this document, and now it is missing?

You have children and now grandchildren? Do they look like you, Mr. Hecht?

You have adopted grandchildren as well. Do they look like you also?

Do they have a right to know who they are — where they came from?

What is your understanding of why Ms. Homes wants this document?

If Ms. Homes is your biological relative, why should she not be treated in the same way as your other equally biological children are treated? Why should she have different, less than equal, rights?

Does that seem fair? Are you a fair man? A just man?

Could you please repeat for the record your name?

And Mr. Hecht, could you please for the record state the names of all your children?

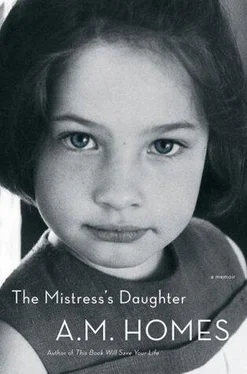

Jon Homes, Jewel Rosenberg, and A.M. Homes

Jewel Rosenberg, my grandmother, my adoptive mother’s mother, graceful, grandiloquent, profound. She is in some ways why or how this book exists. I am not sure that I would have become a writer if it weren’t for her, nor would I have gone to such lengths to become a mother. Without Jewel Spitzer Rosenberg there would likely be no Juliet Spencer Homes — a girl who is now almost three, with no biological relation to my grandmother yet bearing a striking physical relation to her.

When the events charted in this book began to unfold, my grandmother was too old to make good sense of them and my mother elected not to tell her about the return of my biological parents. That decision bothered all of us — my grandmother was the ruler of the family, the queen bee; she was the one we went to about everything, the one with good advice, the one who was remarkable.

She was born in June of 1900, the turn of the twentieth century, in North Adams, Massachusetts. At fifteen she got glasses, looked up at the sky, and saw it wasn’t all black — for the first time she realized there were stars. At sixteen, enrolled at North Adams Normal School (Massachusetts State College) and studying to be a teacher, she was called into the president’s office and told she would never get a teaching job because she was a Jew. She didn’t tell anyone about the incident — except her brother Charlie.

In my grandmother’s house there was a table built in the year of my birth by the Japanese-American artisan George Nakashima from wood my grandmother selected at his shop in New Hope, Pennsylvania. The table is seven feet long, lush — French walnut. It is subtle, not announcing itself as something special until you spend time with it, until you get a feel for it. Then its significance becomes clear.

This was the family seat. This was where we gathered, where my grandmother, our matriarch, held court, where her brothers and sisters and their children and their children’s children came to celebrate, to discuss, to mourn.

There have been great multigenerational political and philosophical debates at this table, especially when my grandmother’s brothers Charlie and Harold would visit — the family radicals. They put themselves through college, changed their name from Spitzer to Spencer, ostensibly to protect the family from their radical reputations, but conveniently also hiding their Jewishness. They both studied law but never practiced. Charlie went to work in a Chicago steel mill and became a union organizer, and Harold married the dancer Elfrede Mahler and went to Cuba, where he taught English and she became the head of Cuba’s modern dance movement. When they came to town, we would spend hours at the table, debating everything from the current political situation to the lyrics of songs they made up as children.

This table was where my grandmother fed us. She had long ago taught herself to prepare the traditional French cuisine that my grandfather had grown up with — and had long ago progressed from a Massachusetts farm girl to a seriously sophisticated intellectual.

As a writer I think of narratives — family stories. Growing up, I was never sure about whether or not I could or should absorb the family history. At family gatherings great-aunts and-uncles from around the world would pull their chairs in close and tell stories about life on my great-grandparents’ farm in North Adams, Massachusetts. I fell in love with these stories, felt attached to them, but also was made uncomfortable — this agreed-upon narrative was not my narrative. “It’s not my history, not my family,” I would whisper to my mother. “We are your family, believe me,” my mother would say. I wanted to believe, but something felt off, inorganic.

Growing up, I had two adopted cousins who were black — they lived in upstate New York and we didn’t see them all that often. Once when we were all at a relative’s house for dinner — the adults downstairs, the three of us playing in the upstairs bedroom — I said, “I’m adopted too,” trying to make a connection. The cousins looked at me blankly—“No you’re not.” “Yes I am.” I was insulted that they didn’t believe me — it didn’t occur to me then that because I was white like my parents they thought I couldn’t possibly be adopted. “Mom, am I adopted?” I yelled downstairs. “What are you children doing up there?” was the answer.

When she was in her late nineties I would visit my grandmother at her home outside of Washington every couple of weeks. We sat at the table and drank tea and talked. While we talked, she rubbed the table, her hand unconsciously moving in circles as if polishing the wood, repetitiously stroking it like a talisman, for comfort, for the giving and getting of wisdom.

We each sat in her familiar place, my grandmother at the head, I just to the left.

At her age, she was perhaps now even older than the tree the table had come from — in my mind they are inexorably bound.

Читать дальше