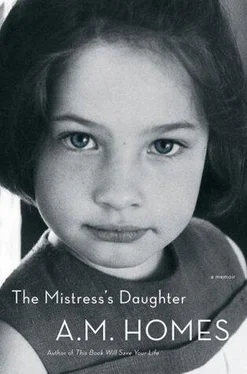

A. M. Homes

The Mistress's Daughter

In memory of Jewel Rosenberg and

in honor of Juliet Spencer Homes

There are two ways to live your life — one is as though nothing is a miracle, the other is as though everything is a miracle.

ALBERT EINSTEIN

A.M. Homes

Phyllis and Joe Homes

Bruce Homes

A.M. and Jon Homes

Iremember their insistence that I come into the living room and sit down and how the dark room seemed suddenly threatening, how I stood in the kitchen doorway holding a jelly doughnut and how I never eat jelly doughnuts.

I remember not knowing; first thinking something was very wrong, assuming it was death — someone had died.

And then I remember knowing.

Christmas 1992, I go home to Washington, D.C., to visit my family. The night I arrive, just after dinner, my mother says, “Come into the living room. Sit down. We have something to tell you.” Her tone makes me nervous. My parents are not formal people — no one sits in the living room. I am standing in the kitchen. The dog is looking up at me.

“Come into the living room. Sit down,” my mother says.

“Why?”

“There’s something we need to talk to you about.”

“What?”

“Come and we’ll tell you.”

“Tell me now, from here.”

“Come and we’ll tell you.”

“Tell me now, from here.”

“Come,” she says, patting the cushion next to her.

“Who died?” I say, terrified.

“No one died. Everyone’s fine.”

“Then what is it?”

They are silent.

“Is it about me?”

“Yes, it’s you. We’ve had a phone call. Someone is looking for you.”

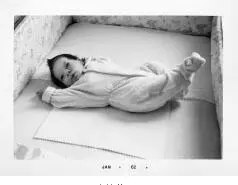

After a lifetime spent in a virtual witness-protection program, I’ve been exposed. I get up knowing one thing about myself: I am the mistress’s daughter. My birth mother was young and unmarried, my father older and married, with a family of his own. When I was born, in December of 1961, a lawyer called my adoptive parents and said, “Your package has arrived and it’s wrapped in pink ribbons.”

My mother starts to cry. “You don’t have to do anything about it, you can just let it go,” she says, trying to relieve me of the burden. “But the lawyer said he’d be happy to talk with you. He couldn’t have been nicer.”

“Tell me again — what happened?”

Details, minutiae, as though the facts, the call-and-response of questions asked and answered, will make sense of it, will give it order, shape, and the thing it lacks most — logic.

“About two weeks ago we got a phone call. It was Stanley Frosh, the lawyer who took care of the adoption, calling to say that he’d gotten a call from a woman who told him that if you wanted to contact her, she’d be willing to hear from you.”

“What does that mean, ‘willing to hear from you’? Does she want to talk to me?”

“I don’t know,” my mother says.

“What did Frosh say?”

“He couldn’t have been nicer. He said that he’d had this call — the day before your birthday — and he wasn’t sure what we would want to do with the information, but he thought we should have it. Would you like to know her name?”

“No,” I say.

“We debated about whether or not to even tell you,” my father says.

“You debated? How could you not tell me? It’s not your information. What if you hadn’t told me and something happened to you and then I found out later?”

“But we are telling you,” my mother says. “Mr. Frosh says you can call him at any time.” She offers Frosh as though talking to him will do something — like fix it.

“This happened two weeks ago and you’re just telling me now?”

“We wanted to wait until you were home.”

“Why did Frosh call you? Why didn’t he call me directly?” I was thirty-one years old, an adult, and still they were treating me like an infant who needed protection.

“Damn her,” my mother says. “It’s a lot of nerve.”

This was my mother’s nightmare; she’d always been afraid that someone would come and take me away. I’d grown up knowing that was her fear, knowing in part it had nothing to do with my being taken away, but with her first child, her son, having died just before I was born. I grew up feeling that on some very basic level my mother would never let herself get attached again. I grew up with the sensation of being kept at a distance. I grew up furious. I feared that there was something about me, some defect of birth that made me repulsive, unlovable.

My mother came to me. She wanted to hug me. She wanted me to comfort her.

I didn’t want to hug her. I didn’t want to touch anyone. “Is Frosh sure she is who she says she is?”

“What do you mean?” my father asked.

“Is he sure she’s the right woman?”

“I think he’s fairly certain it’s her,” my father said.

The fragile, fragmented narrative, the thin line of story, the plot of my life, has been abruptly recast. I am dealing with the divide between sociology and biology: the chemical necklace of DNA that wraps around the neck sometimes like a beautiful ornament — our birthright, our history — and other times like a choke chain.

I have often felt the difference between who I arrived as and who I’ve become; layer upon layer piling up until it feels as though I am coated with a bad veneer, the cheap paneling of a suburban recreation room.

As a child, I was obsessed by the World Book Encyclopedia , the acetate anatomy pages, where you could build a person, folding in the skeleton, the veins, the muscles, layer upon layer, until it all came together.

For thirty-one years I have known that I came from somewhere else, started as someone else. There have been times when I have been relieved by the fact that I am not of my parents, that I am freed from their biology; and that is followed by an enormous sensation of otherness, the pain of how alone I feel.

“Who else knows?”

“We told Jon,” my father says. Jon, my older brother, their son.

“Why did you tell him? It wasn’t yours to tell.”

“We’re not telling Grandma,” my mother says.

This is the first important thing they’ve elected not to tell her — she is too old, too confused to be of help to them. She might do something with it in her head, conflate the information with other information, make it into something entirely different.

“Think of how I feel,” my mother says. “I can’t even tell my own mother. I can’t get any comfort from her. It’s awful.”

My mother and I sit in silence.

“Should we not have told you?” my mother asks.

“No,” I say, resigned. “You had to tell me. It wasn’t a choice. It’s my life, I have to deal with it.”

“Mr. Frosh says you can call him anytime,” she repeats.

“Where does she live?”

“New Jersey.”

In my dreams, my birth mother is a goddess, the queen of queens, the CEO, the CFO, and the COO. Movie-star beautiful, incredibly competent, she can take care of anyone and anything. She has made a fabulous life for herself, as ruler of the world, except for one missing link— me.

Читать дальше