“I’m angry with you, can you tell?”

“Yes.”

“Why won’t you see me?” she whines. “You’re torturing me. You take better care of your dog than you take of me.”

Am I supposed to be taking care of her? Is that what she’s come back for?

“You should adopt me — and take care of me,” she says.

“I can’t adopt you,” I say.

“Why not?”

I don’t know how to respond. I don’t know if we’re talking in fantasy or reality. What happened to “in the best interests of the child”? Who is the parent and who is the child? I can’t say I don’t want a fifty-year-old child.

“You’re scaring me,” is all I can manage.

“Why won’t you forgive me? Why are you always angry with me?”

“I’m not angry with you,” I tell her and it is entirely true. Of all the things I am, I am not angry with her.

“Don’t be angry with me forever. If I’d known where you were I would have come and gotten you and taken you away.” Imagine that — kidnapped by one’s own mother, the same mother who had given you away at birth. She lived not two miles from where I grew up, and luckily didn’t know who or where I was. I cannot imagine anything more terrifying.

“I’m not angry with you.” I am horrified at the way I see myself in her — the loose screw is not entirely unfamiliar — and appalled that in the end I may end up rejecting the one person I never had any intention of rejecting. But not angry. Not unforgiving. The more Ellen and I talk, the happier I am that she gave me up. I can’t imagine having grown up with her. I would not have survived.

“Have you heard from your father? I’m surprised he hasn’t been in touch.”

It occurs to me that “my father” may be having the same reaction to her that I’m having, that he equates me with her, and that may be one of the reasons he’s keeping his distance. It also occurs to me that he may think that she and I are somehow in this together, conspiring to get something from him.

I write him a letter of my own, letting him know how surprised I was by Ellen’s appearance, and suggesting that, while this is something neither he nor I asked for, we try to deal with things with some small measure of grace. I tell him a little bit about myself. I give him a way of contacting me.

I go to the gym. Overhead there is a bank of televisions, CNN, MTV, and the Cartoon Network. I am watching a cartoon in which a basket containing a baby bird is left outside a wooden door carved into the base of a tree. The words “Knock, Knock” appear on the screen. A large rooster opens the door and picks up the basket. A note is pinned to the fabric covering the basket.

Dear Lady,

Please take care of my little one.

Signed,

Big One

The rooster looks inside; a small but feisty baby bird pokes up. The rooster gets excited. An image of the baby bird in a frying pan dances in the rooster’s head. A chicken wearing a bonnet comes into the house and shoos the rooster away. The rooster is disappointed. I am on the treadmill, in tears.

A couple of months pass. It is a cold night between the end of winter and the beginning of spring, and I am in Washington, D.C. I have spent an hour circling my father’s house, wondering why he hasn’t answered my letter.

I am a detective, a spy, a bastard. The house is large; there is a pool, a tennis court, and a lot of cars in the driveway. I sit outside under the cover of night, imagining him with his family, his wife, his other children.

I am on the outside looking in, the interior lights lay bare their lives. The lit windows are like light boxes illuminating X-rays.

From the outside, it looks as though he has it all and then some. The walls in one of the upstairs rooms are painted a deep forest green, with white trim around the edges. I imagine it as a library.

I see a girl pull back the curtain and look out — is she my sister?

There is a For Sale sign in the front yard. I imagine calling the realtor and taking a tour, moving from room to room like a true ghost, unseen, unknown, gathering information, looking in closets, cupboards, acquiring false intimacy by passing over their things, witnessing how they live, which way they unroll the toilet paper, what books are by the side of the bed.

I sit outside the house until I have had enough and then crawl back to my parents’ house.

There is a message on my answering machine at home in New York — the voice raspy, accented, coarse. “Your cover is blown. I know who you are and I know where you live. I’m reading your books.”

I dial her immediately. “Ellen, what are you doing?”

“I found out who you are, A.M. Homes. I’m reading your books.”

It is the only time in my life that I have regretted being a writer. She has something of mine and she thinks she has me.

“How did you get my number?”

“I’m very clever. I called all the bookstores in Washington and asked them, ‘Who is a writer from Washington whose first name is Amy?’ At first I thought you were someone else, some other Amy who wrote a book about God, and then one of the stores helped me and gave me your number.”

She stalks me. I stop answering the phone. Every time the phone rings, every time I call in for messages, I brace myself.

“Do you live with someone on Charles Street? Is he there? Does he not like it when I call?”

“How do you know I live on Charles Street?”

“I’m a good detective.”

“Ellen, I find it very upsetting. How do you know where I live?”

“I don’t have to tell you,” she says.

“Then I don’t have to continue this conversation,” I say.

“Why won’t you see me? Do I have to come up there and find you? Do I have to come up to Columbia University and hunt you down? Do I have to wait in line to get your autograph?”

“I need to be able to do my job. I need to teach my classes and go on my book tour and do all the things I’m supposed to do without worrying that you are going to hunt me down. You can’t do that. I have to be able to lead my life.”

“I need to see you.”

There are no limits. It is all about her need, incessant and total — she wants more and more. I am not allowed to have any rules. I am not allowed to say no.

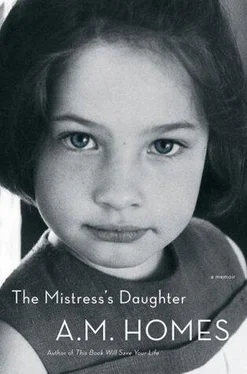

Sometimes as a child, I would cry inconsolably. I would bellow, a primal cry, so deeply guttural, cellular, and thoroughly real that it would terrify my mother.

“Stop, you have to stop. Can you hear me? Please stop.”

If I was able to speak at all, the only thing I would say was, “I want my mom. I want my mom.” Again and again — an incantation. I would repeat it endlessly, comforting myself by rubbing back and forth over the words. “I want my mom, I want my mom.”

“I’m right here,” she would say. “I’m your mother. I’m all the mother you’ve got.”

After Ellen came back, I never cried that way again. I was longing for something that never existed.

The lack of purity became clear to me — I am not my adopted mother’s child, I am not Ellen’s child. I am an amalgam. I will always be something glued together, something slightly broken. It is not something I might recover from but something I must accept, to live with — with compassion.

I want my mom.

“Do you wish she hadn’t come back?” my mother asks. “Do you wish we hadn’t told you?”

“It wasn’t your secret to keep.”

Do I wish she hadn’t come back? Sometimes. Yes. But once it happened, I wouldn’t have wanted to stop the flow of information. It is about fate, the life cycle of information. Once I know something, the amount of effort it takes to deny it, to suspend knowledge, is enormous and potentially more dangerous than to simply move along with it and see where it takes me.

Читать дальше