It was a rolling city and not at all the populous and filthy ruin of traipsing photographers who sought children, derelicts, pigeons, Gushing Hydrant in Harlem, or that old favorite of the Guggenheim Fellow: Ragged Beggar on Wall Street. In my pictures, New York was an ocean liner, unsinkable and majestic, with a lovely curvature from port to starboard, steering seaward on the flood tide of its two rivers, New Jersey and Brooklyn the smoky headlands of friendly coasts. I envied New Yorkers as I envied sailors, and always portrayed them as adventurers with iron stomachs and sea legs, who regarded their glamor with irony and treated visitors as faint-hearted passengers who’d soon disembark. Today there was a gale and the decks were awash.

Weston had recommended the shop Camera Obscura on Second Avenue. It was an uncompromisingly dingy place that catered to what he called “real artists like us,” though I doubt that he was including me in that description.

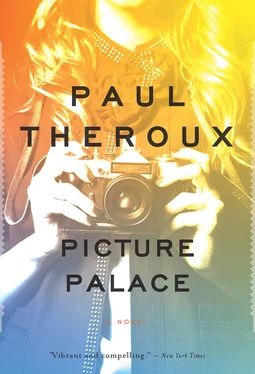

“I want to see a Speed Graphic, please,” I said to the clerk, who had raised his eyes to me and spread his fingers on the counter.

He sized me up, giving me a chance to decode his own features: polka-dot bow tie, elastic bands on the biceps of his sleeves, restless skinny hands, Harold Lloyd glasses, and too many teeth. His face fit his skull tightly like a zombie’s mask and chasing his smirk was a contradiction of irregular bone.

“You don’t want anything as fancy as that,” he said, and plucked from behind the counter a goggle-eyed idiot box the size of a lobster trap. “Take this, madam. It’s so simple a child can operate it.”

“Sounds just the thing for you,” I said. “Now show me the Graflex.”

This annoyed him, and hoping to put me in my place he went to the stockroom and came out carrying an eight-by-ten monstrosity on a tripod. It was something between a whopping doodad for colonic irrigation and a kind of magician’s outfit of mirrors and slots out of which rabbits, boiled eggs, and nosegays of silk flowers were produced. Dangling from its snout was a long hose with a rubber bulb.

“Course if you’re really serious about photography you’ll want one of these.” He piled the equipment on the counter — lens hood, lenses, filters, film, plates, film holders — then pursed his lips at me in smart-alecky satisfaction.

“I said a Speed Graphic. Do I have to sing it?”

“This is the best camera we’ve got—”

He ignored my icy stare that was telling him, in a wintry way, to shove it.

“—get beautiful results with this little number.” He grasped the rubber bulb and, leering at me, gave it a salacious squeeze. “I bet a girl like you could use something like this.”

“Do I look like I need an enema?”

“Hey, watch it,” he said. Anger made his face a membrane.

“Ask the top photographers, if you don’t believe me. Stieglitz has one. He tells all his people to buy them.”

“I’m not one of his people,” I said. “Anyway, it doesn’t look very portable.”

“You don’t look like you’re going very far.”

I picked up a film holder, a metal sandwich with German words on the crust. “So Stieglitz has one of these, huh? I thought he was still in jail.”

“That’s not funny. Stieglitz isn’t just a photographer. He’s photography.”

I stepped back unconvinced. The clerk had that sour breath I couldn’t help associating with baloney, the liar’s inevitable halitosis.

“If you believe that, you’d believe anything.”

“Who are you?” he cried.

But I kept my temper and demanded to see the Speed Graphic, and when I found the model I wanted, I said, “Wrap it up — and I’ll take a half a dozen of those,” indicating the film holders.

“I’ve got news for you,” he said nastily. “They don’t fit that Graphic.”

“I’ve got news for you , buster. I said I want six of them and some film, and if I get any more of your sass I’ll have a word with the manager. Now start wrapping.”

It had been Stieglitz who’d refused to exhibit my work in New York — the Provincetown show I had had such hopes for. It seemed to me that Stieglitz in denying me this exposure was trying to thwart me in my courtship of Orlando. Of course, he knew nothing of Orlando, but the fact remained that my sole intention in studying photography was ultimately to persuade my brother that his proper place was with me in my darkroom. Stieglitz had spurned my photographs and in so doing had belittled me as a lover.

If Stieglitz didn’t like it, it wasn’t photography. Though I considered him of small importance — simply a man who had bamboozled a doting group of people with his lugubrious attentions — I knew that when Stieglitz loaded his camera the world said cheese, or at least his sycophants thought so. He was enthroned in New York in An American Place, his own gallery, and no one could call himself a photographer who had not first wormed some approval from this dubious man. I supposed I could be accused of bias, but I believed the clearest example of his complete lack of judgment and taste was his failure to recognize me as an original.

This early absence of recognition — I was now thirty-one — was the mainstay of my originality. I avoided photographic circles, and while students of photography gathered in “schools,” their very bowels yearning for “movements,” I had grown to loathe the cliques and seen them as nests of thuggish committee men, shabby and unconfident mobsters of the art world whoring after historians and critics. I blamed Stieglitz for this. His authority had weakened photographers to the point where they hadn’t the nerve to go it alone — they were resigned to being part of his legend. The movement — so frequent in the half-arts — implies a gang mentality; it is the half-artist’s response to his inadequacy, something to do with pretensions of photography, the inexact science that was sometimes an art and sometimes a craft and sometimes a rephrased cliché. The movements begged money from foundations and put themselves up for grants and awarded themselves prizes and published self-serving magazines. A racket, and poison to us originals.

What got up my nose most of all was that many photographers I respected, and some I idolized, had had their work exhibited at Stieglitz’s various galleries. Even Poopy Weston had bought his forty-pound peepshow on Stieglitz’s advice. Weston had shown me how to use it and had said, “You’ll never get anywhere unless you meet Alfred.”

“I hold the view that the work ought to precede the person.”

“He’s seen your work.”

“And he didn’t like it, so he ain’t seeing me,” I said. “I’m not a Fuller Brush man, Westy, and you can tell him I said so.”

Pride is scar tissue. Mine made me wary of a further rebuff, another wound. Yet I was insignificant. I could turn my back on him, but who would notice? Not him. As far as I knew, his back was already turned. I would gladly have killed that man, if only to be given the chance to say why. In every murderer’s mind must be the innocent hope that he will have his day in court, to say what drove him to it.

This homicidal impulse cheered me up at the hotel as I unpacked my trays and stoppered bottles of solutions. I examined my new Speed Graphic and took it apart until it lay exploded on the bed. I loaded the eight-by-ten film holders and futzed with my equipment. At last I sat motionless in the room I had deliberately darkened for my film’s sake. It was still raining in that applauding way but, outside, the luminous descent of liquefied light crowded at the pinhole of the window shade and cast through this imperfection a perfect cone of calm, an image of the windowy city on the wall that I studied until the day, red as a mallard’s eye, was lost in the blaring pit that sloped from evening into night.

Читать дальше