“But they’re against everything that’s sensible — that’s why they’re primitive. But there’s nothing primitive about the Pratts.”

He said, “I thought we were talking about the Overalls.”

“We’re talking about brothers and sisters,” I said. “People like you and me.”

He spoke to the gunwale: “I didn’t think you could get away with things like that.”

“So you’ve thought about it.”

“Of course I have,” he said. I thought he was going to amplify this, but all he said was, “Blanche had me fooled.”

“And me. The funny thing is, ever since she told me I’ve liked her more. I didn’t think she had it in her. You think people are different, but they’re not — they’re as strange as you. I know how she feels, don’t you?”

He considered his thumbs. He said, “I’m glad you told me.”

The wind stirred his hair, an agitation like a process of thought.

He said, “Why am I so happy all of a sudden?”

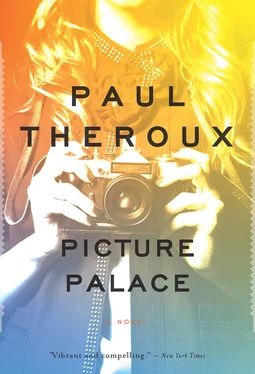

“Ollie,” I said, and kissed him and took his picture: that expression of intense thought draining away and leaving his face lively and untroubled. The sun had set his hair smoldering, and I was soused with sunbeams.

He looked up and saw that we had drifted to the Boston shore. He straightened and gripped the oars and swung the boat around smartly, then — and I could see that it had sunk in — started back to Harvard with swift decisive strokes.

HE WAS back. He returned to Grand Island in the middle of the night and used his own key to make poking clacks at the keyhole, like a burglar’s tired attempt at an inside job. I opened my eyes, blinked away the rust, and rose from the luminosity and chatter of a dream to the dark stillness of the house. It disturbed me: I surfaced, I opened my mouth, the dream trembled, and everything was black.

His noises made him big and busy, a lumbering body. He snapped on lights as he moved from room to room, and then there was that sequence of sounds you only hear at night, that makes its own brief pictures. A door shut and bolted; a spattering jet of bubbles propelled into a bowl; the uncorking of a valve and a chain’s releasing rattle; a collapse of water pressure in the pipes and a fugitive hiss and suck in the walls. The snap, snap, snap of light switches; the complaining stair plank; the resonant crunch of bedsprings; the latecomer’s surrendering sigh in his soft bed.

I subsided into sleep myself and did not wake again until I heard a South Yarmouth lawnmower rat-tatting across the agitated blue of the Sound. It was a beautiful autumn day, a breeze making the sunlight leap from the spiky waves like fire in crystal, and all the long grasses on the dunes brushing softly against the breeze’s belly, He was in and out of the windmill, in and out, the slap of feet and doors, scrabbling in the picture palace. Though in bed I could believe that forty years hadn’t happened — one’s bed is the past — I got up on one elbow and saw him through the window, striding across the lawn with boxes of photographs, carrying my work into the house to examine. I sprang up, put on my housecoat and slippers, and shuffled downstairs into the present.

“You’re at it bright and early, Frank.”

He muttered something about the night bus.

I said, “You strike bottom yet?”

“There’s a hell of a lot more where these came from.” I saw a crude form of criticism, a kind of impatience, in the way he tossed his hair to the side, but his forelock flopped back into his eyes. “If you ask me, I don’t think they’ve ever been touched.”

“I’m counting on you to do that,” I said. “For the life of me, I can’t imagine how they got there.”

His cheeks were dusty. Not even nine and he was already perspiring, the sweat stickling his sideburns and smearing his forearms. He looked — rolled-up sleeves, harassed face, trembling Adam’s apple — like the photographer himself, hugging his property to his chest. He had an artist’s preoccupied air, an artist’s petulence. I was bothering him; I had no business wasting his time. He gasped to remind me that he was hard at work.

“That’s a biggie.”

He weighed the box and said, “Some early ones — the Thirties.”

“Mind if I look?”

“I’m pretty busy, Maude. All this sorting.” Gasp, gasp. “Maybe some other time.”

He frowned and tried to get past me.

“What’s this?”

“Trains, travelers, people at stations. I’m cataloguing them by subject matter as well as date. Topical chronology kind of thing. My faces, my occupations, my vehicles—”

I didn’t mind him saying vee-hickles , but what was this my? “Trains,” I said. “You come across any of Harvard? Charles River? Fellow in a boat, full face, rowing?”

“In the windmill,” he said without hesitating. It scared me a little to realize how thoroughly Frank knew my work: he knew what I had forgotten. He went on, “I’m not putting it with this batch. I’m keeping it for my vessels sequence.”

“I don’t know how you do it,” I said.

Sweat drops flew from his chin as he spoke. “I’m working-flat out. You mind moving? This thing weighs a ton.”

But I stayed on the path. “Coffee?”

“Maw-odd!”

On this return trip to the windmill I stopped him again on the path and said, “The rower — get it for me, will you?”

“It’s right inside the door,” he said. “Didn’t you see it?”

“Didn’t look.”

“Well, look now!” He became a hysterical bitch, jerking his sweaty head and tensing his finger bones.

“Not on your tintype,” I said coldly.

“It’s your thing — they’re your pictures.”

“I don’t go in there.”

“How did the pictures get inside?” he shrilled at me.

“I threw them there. Now listen, you shit-kicker, go in there and get that picture and make it snappy.”

“Right under your nose,” he mumbled, hurrying inside and retrieving it. He dangled it, using his thumb and forefinger to ridicule what he would never understand.

I looked at the picture.

“And there’s some more,” he said. He handed over a chunk of prints.

“I forgot I took so many.”

He glanced at the one on top. “It’s not as busy as your best work.”

“I suppose not.”

He pinched the mustache of sweat from his upper lip and said, “I’ll never finish the retrospective at this rate.”

I withdrew to my room, taking the pictures of Orlando. Hold the phone , I wanted to say. Correction .

The sun had not set his hair smoldering, the river was turgid, and the trees I had remembered as streaming with light were bare. Orlando was dark, hunched over the oars as if sneaking ashore for some furtive assignation. His head was tilted, his ear against his shoulder, and his face, a brown leaf, had a whisper of stealth on it, the wary listening expression of someone who has just heard an unusual sound. His jersey was full of muscular creases, but it was his hands which gave him away, his grip on the oar handles like a hawk’s fists on a branch. His straining stance was more than a rower’s posture: it was flight, he was leaving me.

I had been wrong to remember him gliding downriver in a halo of autumn light. There was no shower of yellow leaves. This was a determined boatman one distant afternoon, who knew it was late and was wasting no time. Those shadows on his face gave him a ferocity that could have been impatient hope trying to displace sorrow, or the anger of thwarted lust. He looked heavy and grave and his back was to the riverbank that seemed a sodden frontier. There were a dozen pictures in all. In the last he faced the camera. He was so private, so engrossed in his mood, he might have been rowing alone. I barely recognized him.

Читать дальше