“Shut up,” Claire said, kicking the place where Alex had jabbed. She felt her foot make contact and Alex went silent. She sipped orange juice and watched the bag. “I wanted to bring him to meet my mother. She won’t be around much longer and I felt it was important,” she said. “Even if it meant her seeing Alex going through this phase.”

“I’m not rightly sure how you see this as a phase,” Ted said. “That kind of verbiage always strikes me as somewhat armchair prophet, wouldn’t you say?”

Claire regarded the bag, which was already beginning to stir again as Alex regained his bearings. “Of course it’s a phase,” she said. “We’ll come out of it together. I can’t have a man fathering children when he won’t even leave his luggage.”

“How does he live?” Ted asked. “How does he feed himself, or use the restroom? Doesn’t he develop terrible sores? What of his work towards his Spirit?”

The Samsonite hopped a little with rage. “We manage, guy,” Alex said from within.

“It’s time to go home,” Claire said.

Ted stood up with her. “I worry,” he said. “He’s exceeding the weight limit on that luggage.” Ted slipped Claire a lined notecard cut down to business card size, his name written on it in marker. Ted closed her hand around the card. “Heaven be with you,” he said.

It was dark by the time they got home. Claire unpacked her own suitcase, a small carry-on barely large enough to hold her clothes. She had rolled Alex back to his place at the foot of the bed. “You’re too heavy,” she said, as she laid him down.

“What a day,” he said. “I’ll be honest with you. I didn’t really want to meet your mother.” Alex tended to be more candid since he had gotten into the suitcase.

“I figured.”

“Had to do it sometime though, babe. You’re real important to me.”

Claire ran her index finger down the handle of the suitcase. “I know it,” she said.

The porch light went dark with a mighty pop that sounded like a kid had shot it with a pellet gun. She thought herself a relatively self-sufficient woman, all things concerned, but she hadn’t yet mustered the organizational skills required to change a light bulb.

“The light,” she said. “I’ll pick another up from the store tomorrow.”

“Plus two sixty-watt candelabra bulbs for the foyer,” Ted said. He knew everything about lights. “Plus, three mini halogens for the dining room.”

“Candelabra.”

“A hundred-watt halogen for the kitchen.”

She rested the sole of her bare foot on the suitcase. “One hundred watts,” she said.

* * *

Ted’s apartment was well-appointed with items from around the world. He told Claire they were gifts from people visiting the chapel. The most extravagant gifts usually came from some poor guy’s family members after Ted administered last rites. People had heart attacks on airplanes all the time, apparently. Ted offered Claire a whiskey with two healthy ice cubes. It was barely noon but she accepted it.

“I didn’t know priests were allowed to drink,” she said.

Ted raised his own glass. “Wouldn’t know either way,” he said. “I’m not ordained.”

“But you gave last rites? That seems illegal.”

“I’m not sure about discussing legalities with a woman who tried to smuggle a man through security.”

“He insisted.”

“And where is he now?” Ted asked. “Hopefully you didn’t leave him in the car.”

Claire swirled her drink. “He likes to stay home. Anyway, he didn’t like you very much.”

“Does he ever come out of the luggage?”

“He sticks his legs out to stretch them sometimes,” she said. “He likes to avoid cramping his legs.”

“Well then, perhaps he is just a man after all.”

“I know he is a man.”

“You haven’t touched your drink.” Ted had mastered the sustained eye contact of the overtly religious.

“I hadn’t thought about it.”

“Well then, perhaps you are just a woman.”

“Really,” Claire said. “Maybe you are on to something.”

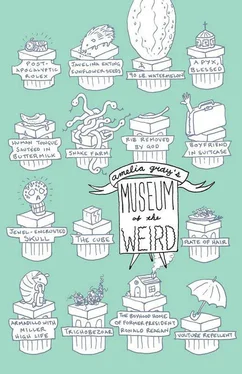

He watched her like a dog watches the door. She stared at him until he looked away. He picked up a jewel-encrusted skull and held it at eye level, ostensibly pondering. “I am interested in the journey towards the Spirit,” he said.

“Are you coming on to me?”

Ted smiled. He made sustained eye contact with the jewel-encrusted skull. “The case of your man, your man in the case. Does he pray or does he meditate? Does he lose the element of his corporeal form, or does his body follow him into the darkness?”

“He does just fine,” Claire said. “He is a fully realized man.”

“I am interested in this man Alex and his journey towards the Spirit.”

“Listen, Ted. Alex lives in a suitcase. Sometimes he sticks his legs out to stretch them. Inside the suitcase, he is nude. He has a fear of commitment.” She tipped back the glass of whiskey. “Honestly, I thought this meeting was going to have a different tone.”

Ted turned to look at her again. “Did you think I was going to make love to you?” he asked. “You have in your possession a fully realized man.”

Claire held her hand over her eyes. “No,” she said. “Jesus. I have to leave, actually. I did not think you were going to do anything like that. Thank you for your time.” She put down her glass and stood to leave.

Ted slipped one coaster under her glass and another under the jewel-encrusted skull. “Heaven with you,” he said.

“Jesus Christ,” she said. “That skull is what’s strange, if you were curious.”

She stopped at the hardware store on the way home. She had forgotten which light bulbs to buy and bought one of everything, and fixtures to match. She bought electric candelabras and heat lamps and mounted sconces and stand-up fixtures. She bought nightlights and Christmas lights and lamps in the Tiffany style.

At home, the suitcase snored. Claire slipped a lock on the zipper and clicked it closed. She surrounded the suitcase with lights, plugged them all into three power strips, and switched them all on at once. The suitcase made a sweet little seed pod under all that hot light. Claire wondered how it felt.

The end of an

As they played, the quartet at Joseph Stalin’s funeral wept for another man. The tyrant lay in state, surrounded by thousands of his closest oppressed, and the greatest string quartet in Russia sat beside his casket and played beautiful music, crying for a dear friend who had died within an hour of Stalin.

The quartet, overbooked, couldn’t make it to Prokofiev’s funeral. Not many could, as it happened at the same time as The Great State Funeral of Joseph Stalin. It must have been harder to believe that Stalin was actually dead. This is a sign of a great man.

There were few flowers for Prokofiev’s funeral, because the flower shops catered to Stalin. All Prokofiev had left in the world was thirty friends and a solo violin. Some of his friends brought flowers from home.

What they provide and how they function (present day)

The university’s hall is packed, fifty more people than were at the man’s own funeral. They are required to be there for credit as music majors. They try to leave at intermission but the ushers won’t give them the programs they’ll need as proof. They put their programs over their faces and sleep. Madeline takes her place on stage.

One little life

Madeline lives her life with the violin. She has been the concertmaster of small orchestras around the world. With her quartet, she once toured China playing Mozart, Bach, and Rolla.

Biographical note

Alessandro Rolla, teacher of Niccolò Paganini; the latter eventually would be known as one of the greatest violin players ever to have lived; cancer of the larynx would take Paganini’s ability to speak, but he was heard improvising frantically on the violin on the last night of his life.

Читать дальше