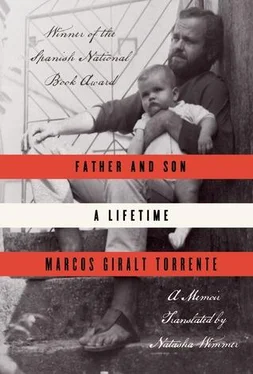

It wasn’t until my first novel that I equipped myself with a spelunker’s helmet to climb down into known depths. And even when I did, it wasn’t intentional. I wanted to write about the insecurities of childhood, and as usual, my desire to write preceded the invention of a story. I remember being paralyzed, unable to come up with anything, until before I realized it, the childhood I was trying to elaborate began to take on elements of my own. The narrator, an adult narrator looking back on his childhood, was an only child, and the epicenter of his family was his mother, with whom he lived and shared the ambivalent memory of an absent father. I lent him the feelings of dread and the thoughts I had at the time, but that was all I took from my own experiences. Or at least so I thought while I was writing it.

My father, however, saw things differently.

Just recently I found out that he was very upset by it, and though the person who told me this isn’t especially trustworthy, in this case the information is credible because I’d previously gotten the same impression. This was very early on, the same day he’d told me he was reading the book. One more drop in the sea of information that flowed between us without need of words.

When you’re an only child, when you don’t have the mirror of siblings, any insecurity about who you are must seem greater than it would if you’d had them, if you’d grown up alongside someone who was shaped by the same influences, who had the same parents and yet was still sharply different from them and — of course — from you. When there are no siblings to turn to, parents are all we have, our only reference, our only vantage point. Everything begins and ends in us, and phenomena like betrayal, love, admiration, or duty are felt with greater intensity. Bonds are stronger or leave more of a mark, and very often it’s hard to distinguish between what’s particular to us and what’s inherited. We have no one to compare ourselves to; loneliness chokes us. Who do we share things with or unburden ourselves to? Who do we go to with questions, answers, accusations? How do we get a measure of distance? How do we construct a balanced account from memory when all we have is a single gaze, and that gaze is shaded — slanted, too — by our own unique selves? When you don’t have siblings everything seems designed especially for you. The danger is that we tend to magnify things, and that from each word spoken to us, each look or slight, each occurrence witnessed (or sensed or reported or even just imagined) we draw infinite conclusions. The result is that we’re bound even tighter and we’re wrong more often too. It may be that we place too much importance on our parents, that the necessary break is harder for us, and it may be that sometimes we don’t value them as much as they deserve. Everything is likely to cause us more pain, and most of all our own singular selves. We’re alone.

This is the only fragment of the whole novel that I would subscribe to in talking about myself: the acknowledgment of my excesses. Otherwise, neither the character of the mother (despite certain vague echoes) nor of the father (an amalgam of bits borrowed from a number of models) resembles my mother or my father, nor was my childhood as claustrophobic as the one described in the book.

I never thought that any kind of connection could be drawn, but clearly I was wrong, for no matter what the characters are like and no matter how different the story is from ours, in some way it portrayed us .

I didn’t have him in my sights. But it had the same effect on my father as if I had.

And I wasn’t unhappy about it.

I discovered that I had a weapon, and I used it.

The first time I consciously availed myself of our problem was in a long story that I wrote for a contest. Under pressure to make the deadline, and afraid that I wouldn’t be able to get a handle on someone else’s story in time, I resorted to a subject I could identify with immediately: a father, a young son, and the triangulation of feelings when there’s dissatisfaction on both sides and one slight leads to another. I chose an isolated and oppressive setting, drastically shortened the time in which the story takes place to ratchet up the intensity, made the narrator take the boy’s side, devised an ending that was theatrical, violent, and unmistakable in its implications, and threw myself gleefully into the writing, swept away by an unfamiliar fury that even led me to scatter clues through the story that my father and his circle would recognize without much effort.

Naturally, there were consequences. A while after it was published and my father had read it, he called one day, and in response to his question about how the new book was coming, I confessed that I was stuck. His answer was, “Stuck? Nonsense. Write about a cruel father and his miserable son.”

What heightened rather more than briefly the guilt this ironic commentary intended to spark was that — though he didn’t know it — the novel I was writing at the time had grown out of that story and was therefore destined to touch on the same subject.

The novel, of course, was more complex than the story, less reliant on insinuation and the careful employment of verb tenses, and more open to digression and a full exploration of the themes. It, too, alternated between two timelines: a recent past that constituted the novel’s present, and a distant, remembered past that functioned as a traumatic explication of the former.

The unresolved conflict that cast a shadow over my narrator’s present was a drama along the same lines as the one I’d presented in the story, an anticipated tragedy that, when it arrives, exposes the guilty parties. The victim was once again a boy, and those responsible for his fate were once again members of his own family: a father unable to act the part and deflect the looming threat, and the father’s wife, trigger of the danger, the instigator. The narrator, like the narrator of the story, participates in the events as an observer, but unlike the narrator in the story — where the action takes place over the course of a weekend — he might have intervened if he chose, which makes his moral position more ambiguous. The reasons he doesn’t intervene — his extenuating circumstances — are his youth at the time of the remembered events and his close relationship to the other three protagonists (son of the instigator, son of the passive father, and half brother of the victim of the injustice described). The simple decision to make the narrator the half brother of the victim allowed me to cast him as a judge of the sins of their common father, much sterner and less prey to charges of Manichaeism than he might have been had he served directly as the victim.

The novel’s other story line, the present-day plot, touched on subjects as varied as love, betrayal, and resistance to assume the responsibilities of adulthood, and there’s no need to summarize it here; suffice it to say that some of the trappings coincided with those of my own life: the narrator’s age, place of origin, social class, and schooling were similar to mine. Also, I scattered so many private references and secret winks for the benefit of those who, like my father, were capable of unearthing them that before I sent the final version to the publisher, I was attacked by remorse and spent a few days deleting or softening the most costly, the crudest, those clothed in the weakest metaphors, those that most transparently betrayed their autobiographical roots, those that gave me the most pleasure to write.

And yet it’s not entirely true, as I suggest in the lines quoted on the first page of this book, that in the novel I killed my father. In the course of the writing, I made the father of the protagonist die for structural reasons, but he wasn’t my father; he didn’t even resemble him. Any connection had to be sought elsewhere. Once the plot was established, I loaned the fictional character some traits of my father’s, through which I sought to direct his attention to the conflict of loyalties played out in the novel, and to the extent that this really was a distorted version of the conflict between us, my intent was to show him something like an image projected on a river, a shadow distorted by ripples of water in motion, an image that hints but doesn’t dictate and could therefore be of anyone. Not a portrait or a true mirror able to return to him a clear image of himself, but rather a cluster of echoes that harked back not only to our story but also to the story of my mother and her father, so similar in many ways to ours that it may have fed my fears, leading to errors of judgment and unfair comparisons that caused me to be too hard on him.

Читать дальше