And none for the departure of the friend he met in Brazil.

And none for being unable to say whether my behavior would have been impeccable if his life had been longer. My cards were marked — I knew he was going to die — but so were his.

Both of us tried. A year and a half of our lives we gave each other.

It’s not fair, then, to torment myself about what might have been. It simply was.

That, too, I owe to him.

The only real guilt that occasionally nags at me: having delayed, having let time nearly get the better of us. And my excess of zeal.

Nothing substantial enough, in any case, to feed all the pages I’ve written.

Having realized this and being able to express it is perhaps the one thing I’ve gained.

In this regard, writing time and living time coincide.

Would I have come to the same conclusion if I hadn’t written it?

Getting used to his death. That’s the main thing I’ve done in all this time.

Death. That which cannot be thought, it’s said.

From the day of his death to the day on which I write this, March 24, 2009, I’ve seen — to the best of my recollection — a Miguel Ángel Campano show, I’ve seen an Albert Oehlen show (both painters he respected), I’ve seen a Kippenberger show, I’ve seen a Darío Villalba show, I’ve seen a Dürer show, I’ve seen a Patinir show; I’ve seen a show titled The Abstraction of Landscape , I’ve seen a Joseph Beuys show, I’ve seen a show of Javier Riera’s photographs, I’ve seen an Alejandro Corujeira show, I’ve seen a Julio Zachrisson show, I’ve seen a show of avant-garde movements in the time of art historian Carl Einstein, I’ve seen a Nancy Spero show, I’ve seen a show of Greco-Roman sculpture, I’ve seen a show of Renaissance portraits, I’ve seen a Picasso show, I’ve seen a Tàpies show, I’ve seen a Rembrandt show, I’ve seen a Twombly show, I’ve seen a show of the work of a Spanish photographer whose name I can’t recall, I’ve seen a Juan Ugalde show, I’ve seen shows in the same gallery by Bendix Harms, a young German I liked, and by Secundino Hernández, whom I’d never heard of, I’ve seen a strident show of contemporary Chinese artists, I’ve seen a show by the Czech photographer Sudek, and the other day, on my way back from doing the shopping, I went into a gallery because I thought I glimpsed a distant resemblance to my father’s final works in the way that space was sliced up in the paintings in the window. Cristina Lama, born in 1977 in Sevilla, was the artist.

And I’m forgetting a few, I suppose. Shows that I saw accompanied by his ghost, as it were.

Many days spent without hearing a person’s voice on the phone are needed to understand his absence; many days spent resisting the impulse to call are needed to understand that he’ll no longer answer; many days spent silencing remarks meant only for him are needed to understand that this is how it will be from now on; many days spent wondering what he’d say about something that we’re well aware he knew best are needed to understand that now our own judgment will have to suffice; many days spent looking at pictures of him are needed to understand that these are pictures of a dead person; many days spent contemplating the objects we inherited are needed to understand that they’re no longer his but ours; many days spent taking stock of common experiences are needed to understand that they’ll never be repeated, that all that’s left of them is the memory. A memory, too, that won’t remain unchanged.

I’ve been down that road. I’ve caught myself thinking about calling my father when he’d been dead for months; I’ve found consolation in gazing at things that were his and then felt the desire to avoid looking at them as my eye grew accustomed to them and made them mine; I’ve saved up questions for the next time I’d see him without realizing that it would never come.

A month ago, going to see a show that I was asked to write about, I felt freed for the first time of his ghost. I was in a hurry, working on deadline, and I hardly thought of him until the next morning, when I saw the article in print and wanted his approval, as I always used to when I wrote about art.

Days later, at a Bacon retrospective, he was on my mind; I couldn’t stop thinking about him. He made the rounds with me, prodding me to reject psychological interpretations and just look at the painting, but it wasn’t enough. I felt a little lost. I needed his commentary, which, though always admiring, wouldn’t have failed to alert me to Bacon’s every slip, every mannerist flaw.

Life doesn’t stop.

Seven months ago, early in September 2008, I learned that I would be a father at the end of the following May. Just a month and a half from now.

Life doesn’t stop. Life has gradually carried me away from him, mitigating his absence. Not the pain, which — though buried deep — is surely the same as it was when I began to write. The same as it will always be. As I write this, with a Django Reinhardt album of his playing in the background, I know with cruel clarity that he is no longer painting in his studio, as I so often imagined him. His studio doesn’t exist, his paintings are in storage, and the next show of his work, if I can manage it, will be a retrospective.

Life doesn’t stop. I’m coming to the end of this book.

If I could turn back the clock and change the way I was for so many years, I would do it, but to say so now, when I already know the ending — even if I mean it — is false tender.

So I think about my unborn son, who will bear his name, and I ask myself how I’ll mold him, how I’ll fail him, what I’ll have to forgive him for, and what he’ll have to forgive me for when — if he doesn’t do it sooner — I, like my father, fade into nothingness.

What he’ll remember fondly about me.

I’d like to preseve some of the best of my father so that it passes on to him through me.

Madrid, April 16, 2009

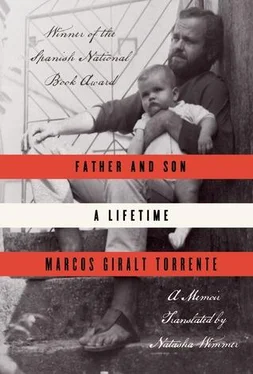

Marcos Giralt Torrente was born in Madrid in 1968 and is the author of three novels, a novella, and a book of short stories. He was a writer in residence at the Royal Spanish Academy in Rome and at the University of Aberdeen, and was part of the Berlin Artists-in-Residence Program in 2002–2003. He is the recipient of several distinguished awards, including the Spanish National Book Award in 2011. His works have been translated into French, German, Greek, Italian, Korean, and Portuguese.

A Note About the Translator

Natasha Wimmer has translated Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 , for which she was awarded the PEN Translation prize in 2009, and The Savage Detectives , among many other works. She lives in New York City.