I was aghast. “Kingslee is a fraud,” I said, “and I will not allow the foetid stink of his dishonesty to fall over this university, this department, or my own achievements.” I informed him that he and his campus overlords in the Main Building ought to thank me for having the courage to defend the institution’s integrity.

“Look,” Fitzgilbert said, avoiding my eyes, “this isn’t personal.”

“The hell it isn’t,” I said. “Botany is nothing if not personal.”

“Yes, well,” he said. “I don’t know about that.”

“Of course you don’t,” I informed him. “You’ve prostituted your soul. You’ve abandoned your work on Aeolia, which was not half-bad, so you can cavort with high-hatted moneymen who want university buildings named for them.”

“Yes, well,” he said. He made some noises about asking Anna Sophia to join us in the office, as if her presence would make his betrayal of me less odious.

“Leave her out of this,” I said. “This has nothing to do with her.”

“Doesn’t it?” he asked.

I had visions of strangling him. “You know,” I said, “there was a time when you had the potential to be mentioned in a breath with, if not Scottwell-Scott, and if not with the few other great men in our field of study, then at least with those about whom, upon their death, one can say with a straight face, ‘He was a damned fine botanist.’ ”

He asked if I was threatening him, an accusation I ignored. “And now?” I continued. “Now you can’t even distinguish between Aeolia altimontii and A. brachyloba!”

“That was one mistake in a treatment of a large genus,” he simpered. “A man makes mistakes. You of all people should understand that.”

“I have made mistakes, but handing garland after garland to a filthy cheat will never be one of them.” Our discussion went on for some time and, I admit, at some volume.

This is what Bureaucracy does to science, reader. Be warned.

In the following weeks, it became evident that Fitzgilbert and Kingslee would exact their revenge in the financial arrangements in re my personal collection. 34and I will not tolerate any further delay in holding these fiends to their promise. Even if the courts do not vindicate me (for they have been as emasculated by cowards and lickspittles as has the academy), I shall go down fighting. Scottwell-Scott would have done no less.

On my final visit to the Mulholland campus (15 February 1925), I was walking through the halls of the biology building when I was accosted by Fitzgilbert and one Officer Raymond Calabash of the Ventura Police Department. They told me that a student had reported seeing me “brandishing” a weapon in the washroom. I informed him that I had been doing no “brandishing” whatsoever; I had merely been cleaning and oiling my old six-shooter, a practice of good maintenance and responsible firearm handling, not to mention an activity that I find calming. Officer Calabash shook his head — such condescension from a supposed public servant! — and asked me why smart people insist on making “stupid” mistakes.

“Excellent question,” I answered. “I take it, then, you’ve read Fitz’s work?”

With Fitzgilbert watching at a distance, clucking his approval, I was roughly ejected from the university to which I gave the best years of my life.

My weapon went unfired, which is unfortunate, as the situation presented an excellent opportunity to impart a few last lessons. In the struggle, though, the officer suffered several sharp kicks to the shin and knee, which must have raised some painful contusions. Just like the Cates boys, Calabash had to limp away from his encounter with H. A. Quilcock, Ph.D. One learns, with age, to take pleasure in one’s small triumphs.

I am grateful that the former Mrs. Quilcock was delivering a lecture at the time of this confrontation and did not have to witness such a miscarriage of justice. Philip St. John Kinglsee was off receiving an award in Geneva — a convenient alibi for someone wishing not to leave fingerprints at the scene of a crime he has orchestrated.

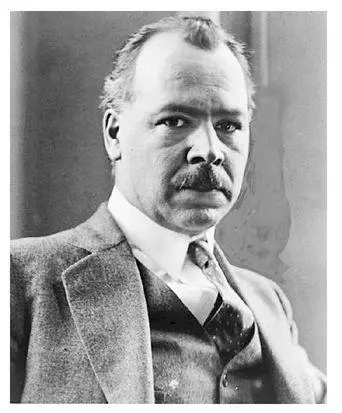

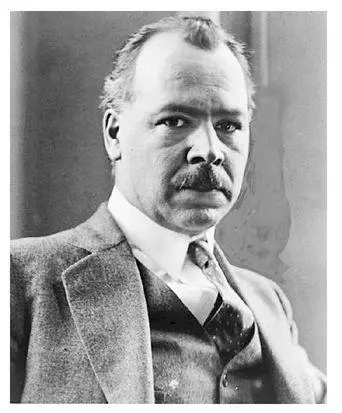

Philip St. John Kingslee

Some may purport to enjoy Kingslee’s company and behave as if his academic work is anything more than a latticework of lies, but this is only because Kingslee has been given the keys to the castle by the monarchs of our realm, which makes him a strategic ally for any up-and-comer. In truth, his overweening opinion of himself is, to any objective observer, repellent.

Of my dealings with him much has been said, written, narrated around campfires. I have attempted to set the record straight as much as my pledge to the former Mrs. Quilcock allows me, and if the world continues to turn a blind eye to the fact that Kingslee has never set foot within five hundred miles of the sky-islands of San Umberto, and refuses to examine more closely the itineraries of the former Mrs. Quilcock and her occasional botanizing companion, Mrs. Beard, in the spring of 1911, well, in the end there is not a thing I can do about it.

It is far from satisfying to limit myself to this brief profile of botany’s greatest disgrace, and I plan to devote an entire volume to Kingslee’s perfidious life once I can no longer do fieldwork. (That is a young man’s game, and lately I have not been feeling at all like a young man. The old digestive problems have returned with a vengeance, I feel flushed with fever, my heart is racing, my teeth feel loose in my gums, and my ears are ringing maddeningly with high-pitched tones. It is time, I believe, for me to leave my writing desk, pour a tall glass of Scottwell-Scott’s favorite Scots whiskey, and turn out the light. As the former Mrs. Quilcock was fond of reminding me, perhaps tomorrow I shall feel better.) 35

S. J. Comerford & Sons

200 Madison Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10016

November 12, 1969

Dr. Jonathan Parker Kingslee

Department of Biology

300 Kingslee Hall

Mulholland University

Ventura, Calif. 93003

Dear Dr. Kingslee,

Thank you for submitting the excerpt from your manuscript, H. A. Quilcock’s Profiles in Botany: A Lost Manuscript Restored.

I regret to inform you that it does not suit our present needs. In short, I do not think the arcana of bygone rivalries in the world of plant taxonomy will be of interest to lay readers. I do think there is a home for this manuscript, although I believe it will be with an academic and not a commercial publisher. Surely you have options other than Stamen? I am no expert in academic life, but surely it is better to publish in a second-tier journal than not to publish at all.

I am curious, though: Do you mean to imply that your father represented your mother’s work on those “skyisland” plants as his own, and that she remained silent about this fraud? Why would your mother agree to cede credit that was deservedly hers? For his benefit? For yours? In her own self-interest? How much did Quilcock know about this deception, and why would he — for the most part — maintain her secret?

You ought to make any such claims explicitly; contemporary readers have neither the time nor the inclination to engage in a great deal of inference. If you do choose to add more “sizzle” to the interpersonal relationships about which you write (as Mrs. Beard certainly did in her recent memoir!), then perhaps a publishing house less established than ours will take a chance on your manuscript. Stories of treacherous father figures, long-suffering mothers, and their fractured families are very much in vogue, are they not?

Читать дальше