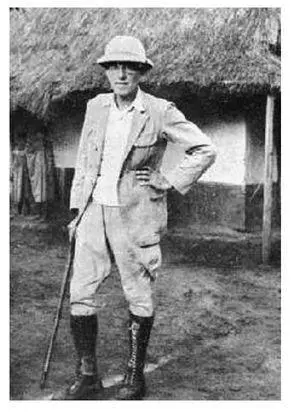

I was introduced to Cates fils — then a gawky, fuzz-faced stripling of nineteen — in San Diego in May 1915 by those subarctic scoundrels Prim and Gjetost, who had hired him (without my consent, and at my shared expense) to drive the wagon, cook, and manage the gear on the ill-fated trip expedition to Valle de Panza. I was told that the boy had a desire to follow in his late father’s footsteps; I suspect, too, that Prim, who had been offering comfort (so to speak) to the recently widowed Mrs. Cates, was doing her a favor by taking the brat out of her hair for a few weeks.

No doubt you have heard this story, reader, but you have heard it only from people with “axes to grind.” I shall attempt to clarify the record once again.

From the outset of the expedition, it was clear that Cates had no intention of performing his duties with any degree of effort, fairness, or respect. He was a ceaseless jabberer and a prolific user of the youthful vernacular that sets an educated man’s teeth on edge. He ignored my needs utterly, preferring to follow Prim like a puppy, practically drenching the tall Norseman’s field tweeds with sycophantic slobber. 32I finally pulled him aside and told him that since I was paying a third of his wages, I expected a full third’s worth of his efforts, and I would be happy to whip him with my own fists if he did not “shape up.” The chastened scapegrace made no further argument for the moment, and afterward, he toned down his toadying mildly — although he made great sport of mispronouncing my surname (sophomorically using a short “o” in-stead of the Anglophilic schwa, such a rapier wit was his) throughout the rest of the trip and, indeed, the rest of his blessedly brief career.

We were five miles west of Lago Romesco, traipsing through the foothills, when I spotted a striking indigo Ptimorus growing in the brush. I did not recognize it, even though I had quite recently made an exhaustive study of the entire Hobaceae family. A closer look revealed that it was, in fact, a new species — the first such discovery that was truly my own. I called a halt to the team so I could collect it. The plant (about 16 cm high, branched at the base, with a 14mm corolla, widely bell-shaped) was in plain view twenty yards off the trail. In my excitement, I made the grave error of calling their attention to the specimen. Their suspiciously muted response should have alerted me to the conspiracy that was then forming between them.

On our way home, we stopped in Tia Juana on a Saturday night and managed to find a respectable inn managed by a white couple. I slept soundly, well pleased with all of my finds, particularly the Ptimorus. We all had agreed to stay over until Monday so as to avoid botanizing or traveling on the Sabbath, but in the morning, Prim was rushing around, saying he had urgent business in San Diego. He would take Cates and the wagon, he proposed, and Gjetost would wait with me until the boy returned for us the next day, if I did not object. As I have always been a man who is respectful of others’ needs, I agreed. I passed the day playing some senseless Scandinavian card came with Gjetost while he prattled on about fjords and ski and warm woolen undergarments. Only later, back in Ventura, did I realize what Prim’s urgent business in San Diego had been: stealing my discovery by sending the plant to Pickwick to have it published before I could attend to it. 33

Cates did not return until Wednesday, and he showed up with his older brother, “Archie Boy,” who was ugly, ill mannered, and of staggeringly subnormal intelligence. They passed by me in the hotel café without saying a word — just giving me the ojo malo, as it were — and went straight up to Gjetost’s room. I knew trouble was brewing, so I went to my room, fetched my six-shooter, oiled it, and loaded it with fresh ammunition. I went down to the street and hitched up the team, hoping to ensure my safety with a quick getaway. My three companions emerged from the hotel, though, all shouts and threats — Gjetost, oddly, still wearing some sheeny night garment, though it was noon — and Archie Boy jumped in front of the horses, took them by the bits, and drawled semi-coherently that I would not be going anywhere until I paid my bill in full. I informed him that the bill was not due until we reached San Diego, and in any event, his impertinent and slack-jawed brother had failed to earn even a fraction of my share of his pay. I leveled the gun at the thick-necked dolt. He foolishly tried to climb into the wagon to get at me, so I shot him in the leg and he fell into the Mexican dirt. Slade shouted at me, so I shot him in the leg, too, then gained control of the spooked horses and left the three of them to “hoof it” across the border, limping like the cloven-footed devils that they were. (Gjetost, cowardly fop that he is, fled at the mere sight of my weapon. Ever since I discovered the theft that Prim and he had orchestrated, I have wished that I had put some lead into his legs, too.) I am proud to say that neither the Cates boys nor the treacherous Vikings ever succeeded in extracting a cent from me.

The story that these “men” told to the San Diego Union reporter when they arrived was just the first of many mendacious accounts of the event, none of which acknowledged how the lot of them had wronged me. The only person who defended my account of the facts in print — and who stands by it even today, I believe — was the former Mrs. Quilcock. She is a far better woman than Philip St. John Kingslee has ever deserved; that much is certain.

Leslie Foxworth Fitzgilbert

The sad tale of Fitzgilbert’s decline is emblematic of the problems that plague the study of botany today. In his younger days, he was a hawk-eyed and methodical collector, a resourceful thinker, and an able steward of taxonomic consistency and decorum. This, lamentably, is a rare combination in our field.

Fitzgilbert, eight years my junior, joined me on the faculty at Mulholland in 1911, a time when the university and the department were held in the highest esteem worldwide. I appreciated him as both a colleague and confidant, just as I had when we were in the field together with Scottwell-Scott. His work in developing a coherent taxonomy of the family Tulaphyllaceae was top-notch. It remains uncontested, and rightfully so.

Unfortunately, Fitzgilbert was insecure as a man and as a scientist, and he fell victim to the siren call of Advancement. In 1911, when he took over the position and the spacious, well-lit office of the dean of sciences (replacing D. B. Plotz, who had died in that same office while “in the saddle” with a second-year coed, a detail that the newspapers still have not got hold of), he ceased to be a serious botanist and became instead a bureaucratic lickspittle and a coward.

I have little regard for lickspittles, and I believe cowards to be the lowest of the low. Yet these days, people of this miserable ilk obstruct the work of serious scientists, instead pledging their spineless fealty to the university or the donors or the trustees or the police, and leaving men of passion and integrity to twist in the wind. I shall never forget the day that “Fitz,” my former friend (and my subordinate on Scottwell-Scott’s expeditions!), appeared in the doorway of my office — costumed perfectly as the ascendant functionary that he was, in his new suit and polished shoes (which were, to my untrained eye, of a quite feminine style) — and informed me that my presence in the department — and, indeed, on the campus — would no longer be welcomed if I continued to “persecute,” “harass,” and “spread lies about” Professor Kingslee.

Читать дальше