His limitations as a botanist aside, he was also a demented little man. Of his behavior in the field I can say little without risking much emotional distress to myself. To those of you who have heard the whispers that he customarily used his plant press in the service of onanism: I shall not be the one to disabuse you of this notion. Since our first and only expedition together, I have refused to handle any specimen collected by him or his assistants.

As if that were not enough: one morning when we were camped on the banks of the Rio Hondo, he delayed our departure by claiming extreme impaction of the colon, owing to a quantity of Mexican cheese of dubious provenance which he had ingested the night before. (I had not partaken, having the sense to limit my diet to tinned foods while in that primitive land.) He then volunteered the information that he needed to “dig himself out.” Perhaps I misunderstood his intentions, owing to his tortured English and lazy diction, but the image that his words conjured will haunt me until they plant my bones in the ground.

The former Mrs. Quilcock always professed respect and admiration for the constipated Frenchman, which I always found baffling, but then, she makes it a practice to search for the best in people. A rare quality indeed, especially in this line of work.

Earl Godfrey Orr

Even at his advanced age, E. G. Orr persists at inflicting his imbecilic work upon us. His “contributions” to systematic botany in general — and to the study of the family Proboscaceae in particular — can only be described as pestilential. An indefatigable supporter of Kingslee, he is also said to be a pederast. 23

Percival Pickwick

Pickwick was Scottwell-Scott’s nemesis and an enemy of science itself. Of his many offenses, the most grievous was his assault on my mentor’s reputation with allegations of academic perfidy (not true), clumsy passes at the wives of colleagues (unverified and unlikely), sadistic treatment of assistants (never), and excessive ingestion of both spirits and the various plants sacred to southwestern cave-dwelling tribes (exaggerated, and none of Pickwick’s damned business, regardless). I shall not discuss any of his accusations further, as they belong in the ash heaps of history and not to works of academic integrity such as this.

Proof is still being gathered, but I believe that Pickwick sent minions out to infiltrate various herbaria to destroy the type specimens of many species described by Scottwell-Scott so that these species could be recollected, redescribed, and renamed by the dastard himself (e.g.: Involvulus pickwickii, Zosum pickwickii, Pflugeria pickwickii). Also, like that villain Gjetost, 24Pickwick used his connections to money and power shamelessly. He obstructed Scottwell-Scott’s funding, added my mentor and me to the secret blacklist at Stamen, and arranged for the publication (in Stamen, of course) of Kingslee’s traitorous review of Scottwell-Scott’s magnum opus, An Omnibus Guide to the Western Flora, in which he made great sport of pointing out minor errors in the manuscript.

One of these, the manual’s confusion of Claemium bakerii and C. minor, was, in all candor, a result of my own carelessness as I helped Scottwell-Scott prepare the manuscript. I am not above admitting my mistakes, and in any event, Scottwell-Scott delivered to me a reprimand that has served me well in all of my work since, emphasizing as it did the importance of meticulousness. It should be noted that the mistake is a common one; as I demonstrated in Flora of Coahuila, 25these two species never should have been separated to begin with. In that volume, I proposed that the proper “lumped” species be named S. aeneii, by way of honoring my ailing mentor, but my suggestion (like most of my work) has been studiously ignored by the despots in our field and the henchmen on their payrolls.

But I digress. In the wake of Pickwick’s and Kingslee’s calumnious campaign of mockery and destruction, An Omnibus Guide to the Western Flora was pulled from publication. Scottwell-Scott was never the same, withdrawing into seclusion, keeping even his allies at a great distance, and sitting idle as his mind and body deteriorated. He had always said he wanted to die while still doing his work—“in the harness,” as it were — but these villains robbed him of the ability to do so. I have vowed not to let them grind me down in the same way.

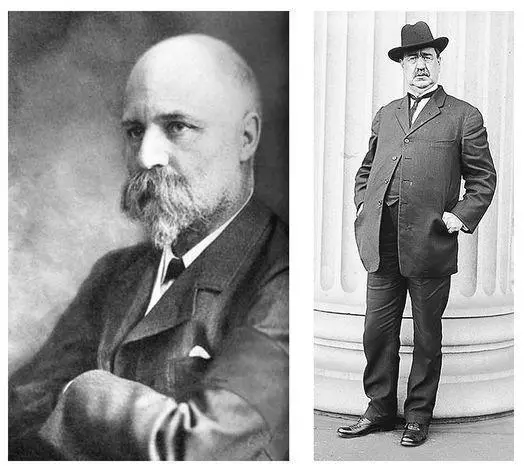

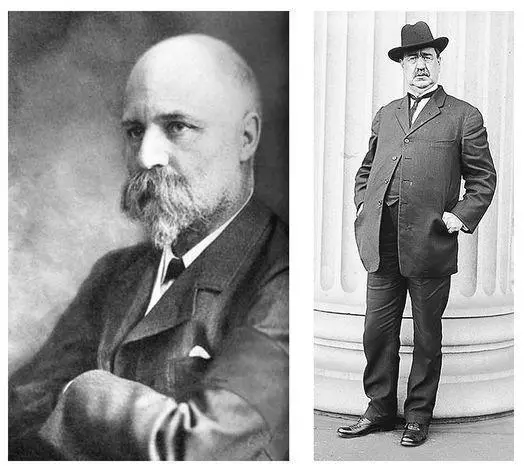

Axel Prim and Per-Fridtjof Gjetost

Together, these photographs of Prim and Gjetost make a diptych of thievery, mendacity, and manipulation: Prim, an unrepentant thief and a festering wen on the nether parts of honest botany; Gjetost, a monied but morally bankrupt fool and four-flusher. These two Norsemen worked together so closely that one wonders how they could tell whose trouser pockets were whose.

For decades they perpetuated their slander of me by repeating ad nauseam all the hoary falsehoods about my part in the Cates debacle and my claim of primacy with respect to the species of Ptimorus discovered on that expedition. No doubt they did so at the direction of that other botanical criminal, Kingslee. 26(If only any of these men had put a tenth as much effort into their scholarship as they have done in maligning me!) Their damnable fictions have obstructed the funding of my work, which has caused me much anguish and gastrointestinal misfortune.

Prim, at least, has gone and relieved us from his presence. On a visit to Bergen last autumn, he strode into the path of an onrushing taxicab. (No doubt he believed that people and machines alike were obligated to keep clear as he strolled importantly through the city.) Gjetost, the now-hostless parasite, was last seen crying in his lutefisk and writing the inevitable obituary-cum-hagiography for Prim in Stamen. The sooner he, too, strides in front of a heavy conveyance moving at great velocity, the better. We shall all release a long-held sigh.

It cannot fail to dawn on one that Norwegians, who preserve their fish with lye, preserve their careers with lies. (I customarily leave punning to less serious scribes, but here I cannot resist.)

Mrs. O. O. Beard, née Miss Helen Fair

I cannot think of a single female botanist who possesses any of the conniving, mean-spirited, and destructive impulses that we male botanists have “in spades” (as the young people say). Of course, many botanically inclined women have produced embarrassingly half-witted work (e.g., Mrs. Beatrice Hilpert of Modesto, Calif., in her treatment of the genus Catherwoodia [Stamen, 9:1 33–36] and Mrs. C. P. Grüntz of Fredericksburg, Texas, in her Flora of Gillespie County [1924]), but incompetence alone is no sin, merely an irremediable condition. Incompetence twinned with treachery, however, is responsible for much of what is so damnably wrong with American botanical study today.

Miss Helen Fair is no incompetent. She is without doubt one of the most talented and dedicated herborizers around, with a vast knowledge of flora from Adastra to Zyxum. I have known her since she was in her early twenties, a bright spark of a girl who had not much interest in the mundane business of woo and courtship — not as long as there were Rynesia blooming in the desert! Not when the world lacked a definitive dichotomous key for the vast and complicated Modicaceae family!

Читать дальше