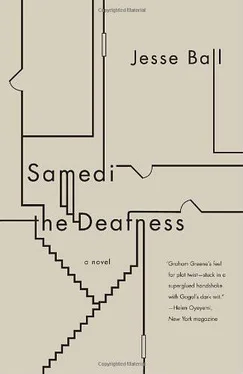

Jesse Ball - Samedi the Deafness

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - Samedi the Deafness» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Samedi the Deafness

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Samedi the Deafness: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Samedi the Deafness»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Samedi the Deafness», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Supper was brought them by a servant, the man who had told James the truth, whom James had wronged. He did not look the man in the eye. He felt embarrassed, and also did not want the man to be found out. Why did the man help me? he wondered.

The material that James held mnemonically was Stark's contraband body of work, his revolutionary writings on what he called The Starkian Play , the act of altering history with a monumental object lesson.

The volume of the writings was large, perhaps six hundred pages of somewhat technical theoretical writings. Ordinarily, James would have given himself far longer to memorize the work, but he knew he was equal to the task of committing it in one night. There was a fear among mnemonists, a fear of stretching the mind to the point where it would actually be broken by stress. It was a fact in chess playing. In certain exhibitions, a grand master would play twenty or thirty games at once, keeping his eyes closed, keeping all the pieces on all the boards separate in his mind, and making in turn his move on each board. Soviet Russia had banned these simultaneous blindfold exhibitions because they shortened the careers of great players.

The door opened. The servant entered again, carrying a tray with a pot of tea, two cups, a tiny milk pitcher, and a plate of sugar cubes.

James looked up from his work and realized he was almost done. The pile at his side had vanished. He closed his eyes and could see the trailing strands of all the books, all the papers. It was a feeling like flying to carry oneself off along these strings of thought and memory and see in long parades of swirling letters all the words, all the pages. He felt confident. He had it all. But there was an odd feeling too. He was preserving the work of a lunatic, of someone who, if the danger was real, would turn out to be one of the most reviled men in history. Did Stark even realize that? Did he expect the world to preserve him and raise him up? If the truth was ever known, he would be vilified, harried from nation to nation. Who would take him in?

— Stark, asked James. What is the plan for when we come out of the bunker?

Stark chuckled to himself.

— Wondering about that, are you? he said.

He went back to the letter that he was in the middle of writing.

— Really, said James. Is there a plan?

— Of course there's a plan. Have you read Boulinard's Strategem ?

James confessed that he had not.

— Well, Boulinard was a medieval French priest. His writings were discovered only in the last fifteen years. It turns out that in the fourteenth century he had come up on his own with a body of work dealing with probability and chance that exceeds not only the work which had been done up until that time but, in fact, all the work done in the centuries since. He's thought of by academics and scientists as probably the smartest human being who ever lived. The discovery of his work was a revelation and spurred a small sort of scientific leap. He's thought of as the founder of modern probability theory, even though his work is in some ways enormously experimental and recent.

Grieve put down the magazine she was reading and came over.

— Where was the work hiding? she asked.

— He wrote it in the margins of illuminated manuscripts, working it into the design so that his writing was imperceptible unless you knew what you were looking for. Once you did you could see that the pages of the Bible were lined with other pages, page after page that he had written. The three Bibles lined with this work had been in a vault unlooked at, save when the occasional high-ranking priest or medieval researcher wanted to look at a sample of original illuminated manuscript.

— How could they look at it and not know? asked Grieve. If it's probability, that's math. Don't the numbers look odd in the midst of the scripts and figures?

Stark went over to a bookshelf, looked for a moment, and pulled down a large volume. He brought it over and laid it flat on the desk, open to a page somewhere in the middle. It was a facsimile of one of Boulinard's Bibles. James looked carefully at the ornament all around the page. At first he couldn't make out anything, but then the figures, the numbers began to appear.

— It's like looking at a carpet, he said.

— The point, continued Stark, is that Boulinard also wrote about plots and strategies. He organized a system that might be used in the creation of conspiracies and coups, and outlined general precepts and guidelines for the administration of such a system. One of those precepts, James, is that, in general though not always, someone who doesn't need to know sensitive information should not be given sensitive information. You will find out where we are going when we go there. Just be glad you are to be saved.

Grieve patted James on the cheek.

— Sometimes you learn more from my father saying no than you do from his yeses.

Stark laughed.

— My daughter loves to tease. How sad I would be if you hadn't been born.

Grieve wore her winningest smile.

— You would be a nomadic horse lord who encamps each night in a tent city far larger than the faces of seven earths unsewn and stretched side by side.

Stark threw back his large head and laughed.

— My daughter, he said, is one of the great fabulists. But she does not like to be found out.

Grieve pretended to pout.

Everything from now on in is a leavetaking, James thought.

— What do you think will happen? he asked Stark. Tomorrow and in the days after?

Stark leaned back in his wide leather chair.

— At first, enormous pandemonium. The populace will discover all at once the fate that has befallen it. Millions of people will make their way through cramped, crammed streets to hospitals, causing untold devastation in motor accidents. Mobs will cause enormous damage. The hospitals, of course, won't be functioning: there is no cure for this. And furthermore, all the workers in the hospital will have gone deaf as well. The fact is, going deaf is the least of the troubles. It will be the lasting effect, and certainly the moral, but the worst danger will be in the economic collapse. The other nations of the world will be in a strange position. It will be interesting to see how they act.

Stark's face was grim, but set in a strange expression of curiosity.

— It will be seamless.

He took a deep breath. Beneath the desk, James could see his hands clench and unclench. A good person, which he may be, thought James, must be torn apart by doing what he's doing. Has any man ever believed he was this right?

Stark was still talking. James realized he had drifted off; he had not been listening.

— We have balloons hidden in hundreds of caches across the country. They will be released up into the atmosphere mechanically, from a remote location. When they reach the proper height, they will burst, and the gas inside will disperse and alter, as it meets with the atmosphere. Then the clouds will form. They will begin to drift and sing. The entire continental nation will be affected. The clouds will maintain themselves for two to three days, long enough to affect the greater part of the population.

Grieve and James were silent for a minute, then another minute, watching him.

Finally, James spoke.

— How do you know how it works? Have you tested it?

— On one person, said Stark. My partner in the laboratory. Morris, Andrew Morris. We drew straws. I would have done it if I had drawn the straw. But he was the expert. He was the one who made the gas.

He smiled vaguely, unsettlingly, as though he were looking at something far away.

— I have his description of the experience, of what it's like to hear the tone from the cloud. In fact, it's the last thing I wanted you to memorize. I've been looking for it all day. I just found it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Samedi the Deafness»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Samedi the Deafness» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Samedi the Deafness» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.