Tom Barbash

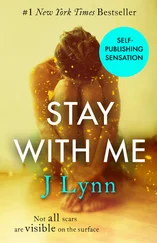

Stay Up With Me

I t was her son’s second night home for Christmas break, and the mother had taken him to a pizza place on Columbus Avenue called Buongiorno, their favorite. The boy was enjoying all the attention. The conversation revolved around him and his friends. He was talking about someone in school who had lost her mind, a pale, pretty girl who’d been institutionalized and who sent a scrawled-over copy of The Great Gatsby to a friend of the boy’s. In the margins, she had pointed out all the similarities between the character’s situation and what she believed to be hers and that of the boy’s friend. She had earmarked pages and scrawled messages. YOU ARE GATSBY, she wrote on the back of the book. I AM DAISY.

The boy’s mother pictured the girl in a hospital ward, aligning her fortunes with tragic heroines, ripping through the classics with a pen. At least, the boy’s mother thought, the insanity was literary. They were taking school seriously, she thought, and she liked that her son seemed to have some compassion for the woman (more than she did; she was simply glad it wasn’t he who’d been the target).

She liked the person he was becoming, liked the way he treated others. He’d had a girlfriend in the spring and then another over the summer and the mother had liked how he opened doors for them, how he listened to what they said, and how he talked of them when they weren’t around. Now both of those were over and done with. She didn’t know much about how they’d ended, only that he’d kept in touch with one and not the other. From time to time the boy glanced toward the front door of the restaurant at the hostess station. The hostess smiled over at them. The boy’s mother was getting used to this. Her son had begun to fill out in the last year, his sophomore year at college, and had become the sort of young man women smiled at, and not only girls his age. Recently one of the mother’s friends saw a picture of him in a T-shirt and jeans and had said, “ Look out .”

The pizza was good and the boy ate a lot of it. The mother looked over and caught the eye of the hostess. A good ten years older than the boy, and not what you’d call pretty. Though thin and busty, she had a somewhat pinched nose and a dull cast to her eyes. The mother imagined that she often went home with men she met at the restaurant. The girls the son had dated were smart and pretty and charming. This woman was not. Her son didn’t seem to notice her but was talking about the coming summer and how he wanted to travel around Eastern Europe, Romania maybe, or Hungary. He’d work half the summer and then take off. He wasn’t going to ask for any money, he said. “How’s the book going?” he asked the mother.

She had been writing a book about Hollywood in the 1950s. She told him about the last three chapters, one on the advent of television and the other two on the end of the studio system. He asked good questions, made suggestions. He was funny. He was her friend.

He left for a moment for the bathroom. The mother watched the hostess watching her son as he crossed the room, as though he were a chef’s special she was hoping to try. The hostess walked back toward the kitchen. The mother couldn’t see either of them now. It’s nothing, she told herself.

But then she was peering around the partition to see what was happening. The hostess was lingering eight or ten feet from the men’s room. How incredibly pathetic, the mother thought.

The boy stepped out. She said something. He said something. Then he was back at the table.

“Should we get dessert?”

“What did that woman say to you?”

“Nothing.”

“I saw her say something .”

“Oh, you know, How’s it going? How’s your meal?”

She was acting like a jealous wife, she thought.

“I think she likes you,” the mother said, though not encouragingly.

The boy smiled, then changed the subject.

They stopped at an ice-cream place on the way home, a store the boy had worked at three summers before. Back home they watched the second half of Anatomy of a Murder on TV, then the mother said she was going to sleep. The boy stayed in the family room to watch more TV.

The mother read for a while. She thought of calling her husband, but then didn’t because she would probably bring up the hostess, then feel ridiculous for doing so. She’d make it a bigger deal than it needed to be. It had been a nice night, she thought. They’d have a few weeks of these and then he’d be gone again, and she’d be alone in the house. She liked his company, and lately she’d been starting to understand that this was the reward for all the work you did, these years of friendship. You watched them become the sort of people you wanted to know.

In the middle of the night she heard voices and she wondered if he’d turned the volume up too loud. She walked back to the family room. The doors were partially open. She peered in and there was the hostess, her shirt off and one of her considerable breasts in her son’s mouth. Her son’s shirt was off, and his eyes were closed. The hostess was straddling the boy’s lap, her chin resting atop his head as he nursed and nuzzled.

She stepped back out and closed the door.

“Shit,” she heard the boy say.

The mother was surprised by what she felt then — not embarrassed, even for him. She felt enraged and invaded, as though someone had broken into her home and stolen something valuable.

“Can you come out here a moment?” the mother said.

He walked out, his hair messed, but his pants still on.

“I’d like her to leave.”

His eyes were on the ground. He looked ashamed, and she knew she wasn’t being entirely fair here.

“And keep your voices down.”

She tried to pinpoint what it was exactly that bothered her about the hostess because she wouldn’t have minded if it were her son’s girlfriend over. She was neither a prude nor a moralist.

There was something about her son picking up a stranger and bringing her back, and using a dinner out with her to do it, that made her feel used and betrayed.

Then she thought: He’s nineteen. He can do what he likes.

She heard the two of them leave through the front door. Her son was walking the woman home, she supposed, which was the right thing to do.

Around twenty minutes later he’d returned. He didn’t knock on her door to complain or apologize. He went to his room and closed the door.

They said nothing about the incident at breakfast the next morning. They read different sections of the paper and talked about what classes he was taking in spring.

The next day the mother was walking to the subway and she passed the pizza place. The hostess looked up from her seating list and saw her through the window. They made eye contact. The hostess smiled, affably and unappealingly (one of her teeth might have been gray). The mother kept walking.

The mother made dinner that night, rosemary chicken and steamed vegetables. The boy was going out with some friends afterward. The mother knew the friends, Oscar, whose father was a producer for Nightline, and Kevin, a math major at Dartmouth who always smelled of coffee. The boy was not home by two o’clock, nor by three. At around four he returned. She thought better of confronting him. There were things she wouldn’t know, and that would have to be okay. Still, she dreamed that night that he’d brought home two women, strippers, and they had tied him to the leather armchair in the family room.

She said nothing the next day. Her work was going slowly. She tried to keep her mind on Howard Hawks and Elia Kazan, but her thoughts kept returning to the hostess. She had altered the atmosphere surrounding the boy’s time home. And now the mother was having trouble meeting her self-imposed deadlines. She went by the restaurant the following afternoon after the lunch tables had cleared. The hostess was refilling hot pepper and grated cheese dispensers.

Читать дальше