SUN SHUYUN

Ten Thousand Miles Without a Cloud

COPYRIGHT COPYRIGHT DEDICATION MAP PREFACE ONE: Bringing Back the Truth TWO: Three Monks at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda THREE: Fiction and Reality FOUR: Exile and Exotica FIVE: Land of Heavenly Mountains SIX: Imagining the Buddha SEVEN: Light from the Moon EIGHT: Not a Man? NINE: Nirvana TEN: Battleground of the Faiths ELEVEN: Lost Treasures, Lost Souls TWELVE: Journey’s End KEEP READING SELECTED READINGS INDEX AUTHOR’S NOTE ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

HarperCollins Publishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollins Publishers 2003

Copyright © Sun Shuyun 2003

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007129744

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007380923

Version: 2016-03-17

Sun Shuyun asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Map by John Gilkes

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

For Robert, and my Chinese family

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

MAP

PREFACE

ONE: Bringing Back the Truth

TWO: Three Monks at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda

THREE: Fiction and Reality

FOUR: Exile and Exotica

FIVE: Land of Heavenly Mountains

SIX: Imagining the Buddha

SEVEN: Light from the Moon

EIGHT: Not a Man?

NINE: Nirvana

TEN: Battleground of the Faiths

ELEVEN: Lost Treasures, Lost Souls

TWELVE: Journey’s End

KEEP READING

SELECTED READINGS

INDEX

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Xuanzang, the subject of this book, could not have completed his epic journey without the help he received from kings, emperors and princes. I too have to thank a large number of people who made my journey possible; they helped me practically and intellectually. They include R. C. Agrawal, Daub Ali, Swati Barathe, Vasanta Bharucha, Bodhisen, Peter Coleridge, Joe Cribb, Mick Csaky, G. P. Deshpande, Toby Eady, Elizabeth Errington, Katie Espiner, Anthony Fitzherbert, Madhu Ghose, Richard Gombrich, Ruchira Gupta, Sue Hamilton, Hu Ji, Prem Jha, M. C. Joshi, Shah Nazar Khan, Robert Knox, Luo Feng, Philip Lutgendorf, Ma Shichang, Manidhamma, Robert Mason, Jean McNeil, Venerable Miaohua, Yumiko and Paul Mitchell, Vivek Nanda, Lolita Nehru, John Pell, M. C. Ranganathan, Harapasad Ray, Gowher Rizvi, Virginia Shapiro, Sarah Shaw, Romila Thapar, Judy and John Thompson, Uma Waide, Wang Qihan, Roderick Whitfield, Sally Wriggins, Zhang Jianhua, and many other friends and experts in China and elsewhere too numerous to list. I must single out Sally Wriggins, whose academic study of Xuanzang has been invaluable.

I owe an especially large debt to five people:

to Susan Watt, my editor at HarperCollins, who saw I had a book to write before I did, who had confidence in me before I acquired it myself and who led me through the new experience of writing with insight and assurance;

to Fang Xichen, who has been nothing less than an inspiration on the history and culture of my own people, a man of real wisdom and generosity;

to Venerable Dr Jingyin, who has been my guide and teacher in the vast canon of Buddhist writings, and who, with immense kindness, has shared with me his broad understanding of his faith;

to Tapan Raychaudhuri, whom I have troubled again and again, yet have always been received with warmth. He has put at my disposal his great knowledge of Indian history, not to speak of his expertise in Pali, Sanskrit, Indian literature and much else besides;

and above all to my husband, who kept encouraging me to write the book in the first place, who tolerated with the mildest of complaints my long absences abroad and who remained calm, patient and supportive throughout. Of all the people I know he comes closest to having the qualities of a Buddhist.

SUN SHUYUN

Bringing Back the Truth

I GREW UP in a small city in central China, in a time that now seems remote and strange. It was the 1960s. Life went by like scenes in a play I could not understand.

At first it was much the same every day, just Mother, Father, Grandmother and my two older sisters in our house in a military compound; nobody smiled much, never any treats. Things only livened up for the few days of the Chinese New Year. We ate sweets, and dumplings with meat in them; we had new clothes and a few pennies of pocket money; we bought firecrackers, watched puppet shows, put bright red posters on the front door and beautiful paper cut-outs in the windows.

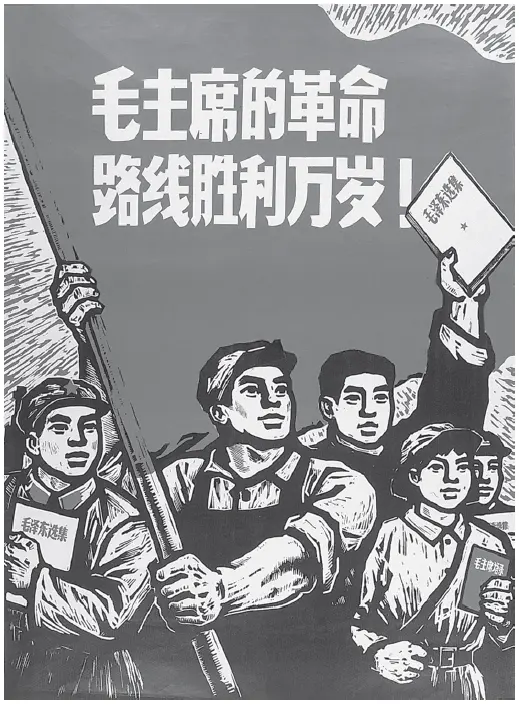

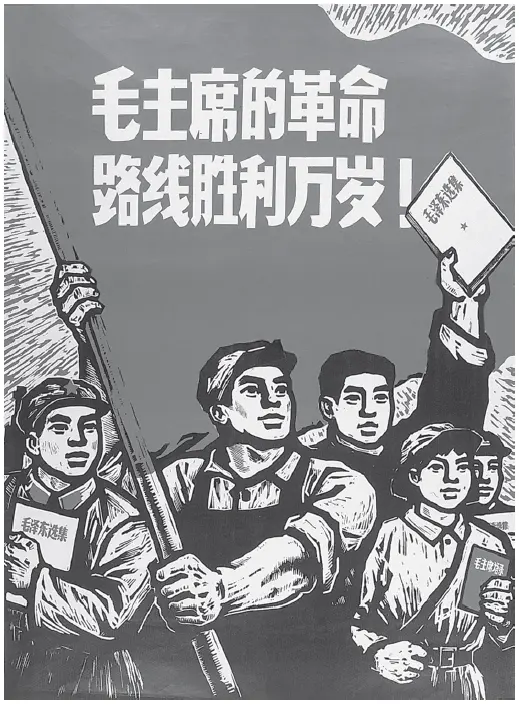

Suddenly everything changed, and the streets were alive, as if every day was the New Year. There were posters, red, green, pink and yellow, waving in the wind, or blown along the road; flags flew on top of houses and workplaces; walls were painted with portraits of Mao. Loudspeakers blared out revolutionary songs from morning till night. Young men and women from Mao’s propaganda teams recited from his Little Red Book , twirled about in ‘loyalty dances’, and struck revolutionary poses – they never seemed to tire, but sometimes they fainted and had to be carried away. Some of them even pinned Mao’s portrait on their chests, and their blood dripped down. The Cultural Revolution was on the way.

Often the whole city turned out in force. People walked in ranks, some holding little paper flags, others carrying huge banners, everyone shouting slogans, young girls and women jumping up and down to the sound of cymbals and drums, with firecrackers sounding off. It was like the pageant shows during the New Year, with farmers walking on stilts, acting pantomime lions and donkeys, and dressing up as popular characters from folklore. When I asked my parents why they were marching today, the answer was nearly always the same. There was a new dictum from Mao! People stopped whatever they were doing and took to the streets, pledging their loyalty.

Another popular event was the frequent parading in the streets of what we called the ‘enemies’ of the people. They all wore dunces’ caps, and had huge placards hanging from their necks, the black characters of their names cancelled by big red crosses. There were landlords in their silk jackets, and their wives with painted faces and heads half-shaved; teachers had their shirts splashed with ink, black, blue and red; some women carried their shoes round their necks – these were bad women who had cheated their husbands; old monks with grey hair and beards wore their long robes torn and smeared with cow-dung. They were all like circus clowns with their make-up; I ran after them, shouting and laughing.

Читать дальше