‘Why all the fuss?’ she asks, as the visitors depart. ‘Is not all soup the same?’

Yet now, at night, when we are going home, we sometimes smell the putrefying truffles from the street, or catch a glimpse of moonlit rowing boats, or look into her kitchen at the back end of the house to see her lifting her lovelorn sailor’s pan onto the hob, or hear the tidal rhythms of the sea as two-parts brine goes by its secret route into her soup. We find her carrying something — skeins? — across the room. They could be wool or seaweed skeins. We cannot tell. We see her fingers in the steam, adding magic touches to the stock. We see her sleight of hand, the charms she uses to entice these strangers to her rooms.

So, for a month or two — for fame is brief and fashions only fleeting — our tables at the celebrated restaurant are taken by new visitors to town. And we must wait — yes, wait and see — until its reputation fades, until there’s room again for us to sit and smoke, to dine and feel at home, to dip our spoons and bread into this new and famous mystery.

WE WERE AWAY ten days. In our absence, something must have shifted in our house, a quake, a tilt, a ghostly hand, a mischievous intruder, some global subsidence. It was enough to make the freezer door swing open. Maybe only slightly at first, just wide enough to fill the kitchen with gelid air. But once the frozen food inside began to defrost, to shed its cold paralysis, the packets and the bags became unstable. They sank and fell against the partly open door. They avalanched. Some packets tumbled out and hit the boards. The wildlife in our house had cause to celebrate. Heaven had provided manna on the kitchen floor and lots of time to feed on it. The distant glacier had calved some frozen meals for all the patient arthropods.

When we returned, the smell was scandalous, a nauseous conspiracy of vegetables and meats and insect waste. The rats had defecated everywhere. The larder slugs had filigreed their trading routes. Someone had left a green-blue mohair sweater inside the freezer, knitted out of mould. The broken flecks of wool were maggot worms and wax-moth larvae. The sweater seemed to shrug and breathe with all the life it held.

We shrugged and cursed. This was the worst of welcomes. We put on rubber gloves, got out the cleaning rags and mops, filled up a bucket with disinfectant and hot water, set about the task of clearing up the food, of pulling out the emerald body from the freezer, of closing once again the slightly open door.

Within an hour we’d restored the ice. Unless you looked inside the empty freezer, saw the lack of frozen food, you’d never guess that we’d been breached and burgled by the teeming universe.

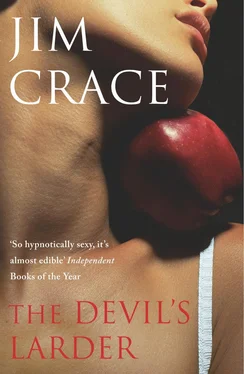

WE WERE brought up not to eat the cores. To do so was considered greedy, messy, ill-mannered and, we were assured, immensely dangerous. Vitalized by our digestive juices and the dark, the pips would swell and strike. An apple tree would spring up and flourish in the warm loams of our intestines ‘like a baby’, until its roots and branches spread and burst out of our sides. Our skins and clothes would tear apart. ‘Then you’ll be sorry,’ mother said.

The only cure, if any pips were to be defiantly swallowed by any of her girls, was a dose of weedkiller and, possibly, if that did not prevent germination, a painful operation with a pair of secateurs. ‘It’s not a story I’ve made up,’ she said. ‘Go down to the orchard and you’ll see how true it is. Look for the faces and the hands of the boys and girls who’ve swallowed cores. They’ve turned into bark.’

I hated orchards then, and apples too. I did not want to end up like the children I’d discovered in the bark, hard and sinewy, distorted by pain, with ants and beetles crawling on their eyes and nothing to protect them from the night.

These days I have recovered from my mother’s house. I always chew the cores. I do not spit the pips into my palm. Indeed, as I grow older, the thought of something new and green, striking life inside me, growing ‘like a baby’, is not a nightmare any more. I rather think that orchards are a better resting place than cemeteries or crematoria. I’d sooner finish as a piece of bark than ash or bone.

I used to tell my only son, ‘Eat the cores. They’re the healthiest bit.’ He did as he was told. Frightened, I suppose, of being ill. But he’s defiant now, I find. Today we drove my grandchildren to school. They had their breakfasts on the hoof. An apple each. I watched them chewing up against the cores like hamsters. I did not dare speak. My son rolled down the windows of the car. ‘Go on,’ he said. ‘See how far they’ll go.’ A family ritual, I am sure. They waited till we reached the open land, between the fast road and the shops. And then the cores went out, flung fast and wide.

‘There’ll be an orchard there before you know it,’ their father said. ‘Those pips are apple trees.’

THIS WAS THE second time she’d died in bed. It was her second burial as well. Nine years before the funeral, the hillside — undermined by summer rain and quarrying — had slipped and piled itself against our neighbour’s house as quietly as a drift of snow. She and her husband were fast asleep, exhausted by a day of harvesting, their suppers still uneaten at their sides. The boulder clay had shouldered all its strength against their stone back wall until their room capsized and the contents of the attic and the flute-tiled roof collapsed onto their bed. My neighbour dreamed, fooled for an instant by the sudden weight across her legs, that the dogs had jumped up on the eiderdown. This was against the farmhouse rules. She was ready in her sleep to knock them back onto the bedroom floor.

Now she and her husband were not sleeping. But they were trapped beneath their sheets, beneath the eiderdown, by rubble from the land and from the house and so could only stay exactly where they were, their heads and chests protected by a porch of beams and timbers, their legs encased by cloth and clay. A stroke of luck. They had been saved from instant death by ceiling beams, stout wood from local trees. They had woken in a dark and sudden tent, closed off from the world.

By dawn the heat was stifling. They tore their night-clothes off and ripped the sheets. They called for help but could tell from the way their voices were absorbed that they would not be heard. They knew that their uneaten supper was within reach. Except there was no reach for them. They could not turn or stretch. The earth was just a finger-length away. They breakfasted on perspiration from their lips and moisture from the clay.

By evening the clay had fixed and baked, entirely dry. They sweated only smells. No moisture any more, and nothing on their lips to drink. They should have died within a day; the heat, the pain, the thirst would put an end to them. But they had worked their whole lives with clod and clay and stone and knew their properties. A thousand times, to stave off hunger in the middle of a task, the old man had popped a pebble into his mouth and sucked. He swore that he could always taste what crop was in the field. So now he searched the rubble with his one free hand until he found the flat, impassive flanks of stones, the ones he’d hauled so many times out of the way of his motor plough. He tugged two stones the size of supper plates free of the clay with his strong fingers and placed one on his wife’s naked stomach and the other on his own. The weight expelled the danger, saved their lives. Their fevers were absorbed by stones. And once the stones had levelled off at body temperature, they were discarded by my neighbours and colder thermostats were found.

The old man and his wife stayed strong with stones. Their bodies grew as gelid as the earth and they could feel their stomachs filling, the slow transfusion into them of rain and sun and harvest crops.

Читать дальше