How’s your chariot-driving? she says.

Put it this way, George says. There’s only one car up here and if I push you, no matter what direction I intend to push you in, you’ll hit it. And if you’re fortunate enough not to hit it –

She points at the steep entry and exit slopes that dip in real suddenness down to the next floor.

Ski-jump, H says. The ultimate challenge.

She glances above her head at where the security camera is. Then she jumps out of the trolley as easily as she jumped in.

Right, she says. You first.

She nods at George then nods towards the trolley.

No way, George says.

Go on, H says. Trust me.

No, George says.

We won’t do the slope, H says. I promise. I’ll be careful. I think we’ve time for one. If there’s time for two and he stays asleep and no one comes up I’ll get you to do me too.

She holds the trolley steady.

She’s waiting.

There’s nowhere for a foothold so George has to balance herself on the sides of it and sort of roll into it and turn herself the right way up again

(ouch).

Ready? H says.

George nods. She braces herself against the sides of the trolley and equally as much against the fact that she isn’t the kind of person who usually does something like this.

Want me to keep hold of it all the way across or just to push it really hard then let it go? H says.

The latter, George hears herself say.

She is quite surprised at herself.

Latter. Fortunate. You use words, H says, that I never hear anyone else using ever. You’re wild.

Literally, George says inside the cage of the trolley.

Latter. Fortunate. Literally. Here goes, H says.

H swings the trolley round so George is facing the expanse of the car park roof. She angles it away from the exit slopes. The next thing George knows is the way she’s forced backwards by a forward shove so strong that for a moment it’s like she’s going in two directions at once.

Later, back at home, George goes downstairs to make coffee and leaves Henry in her room talking to H.

Yeah, that’s her, H is saying. The heroine of the Anger Games.

It’s Hunger Games, Henry says.

Catnip, H says.

Her name’s not Catnip, Henry says.

By the time she gets back upstairs Henry and H are engaged in a kind of verbal ping-pong.

Henry: As blind as?

H: Houses.

(Henry laughs.)

Henry: As safe as?

H: A bell.

Henry: As bold as?

H: A cucumber.

(Henry rolls about on the floor laughing at the word cucumber.)

H: Okay. Switch!

Henry: Switch!

H: As keen as?

Henry: A cucumber.

H: As pleased as?

Henry: A cucumber.

H: As deaf as?

Henry: A cucumber.

H: You can’t just keep saying cucumber.

Henry: I can if I want.

H: Well, okay. Fair enough. But if you can, I can too.

Henry: Okay.

H: Cucumber.

Henry: Cucumber what?

H: I’m just playing it your way. Cucumber.

Henry: No, play it properly. As what as a what?

H: As cucumber as … a … cu–

Henry: Play it properly!

H: Likewise, Henry. Like plus wise.

When H goes home at eleven George literally feels it, the house become duller, as if all the light in it has stalled in the dim part that happens before a lightbulb has properly warmed up. The house becomes as blind as a house, as deaf as a house, as dry as a house, as hard as a house. George does all the things you’re meant to do before bed. She washes, she brushes her teeth, she takes off the clothes she’s been wearing in the daytime and puts on the clothes you’re meant to wear at night.

But in bed, instead of the usual jangling nothing in her head, she thinks about how H has a mother who is French.

She thinks about how H’s father is from Karachi and Copenhagen and how, H says, according to her father, it is actually perfectly possible to be from the north and the south and the east and the west all at once.

She thinks this is maybe where H gets her eyes from.

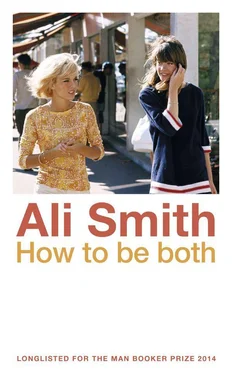

She thinks about the picture of the two French singers on her desk. She thinks about how she might be said to resemble a French girl singer from the 1960s.

She will put that picture up by itself, give it a whole wall like she’s done with the poster her mother bought her of the film actress when they went to the museum in Ferrara and saw the exhibition about the director her mother liked who always used this actress in his films.

She thinks about how she’s never cycled two on a bike before, where one person does the cycling by standing on the pedals and the other person sits on the seat and holds on to her at the waist but loosely enough so that she can continue to move quite freely up and down.

She thinks about how polite H was when she apologized to the security man at the car park. In the end he had seemed rather charmed even as he’d threatened them with the police.

Finally she lets herself think about how it feels:

to be so frightened that you almost can’t breathe

to speed so fast and be so completely out of control

to know the meaning of helpless

to spin across a shining space knowing any moment you might end up hurt, but likewise, all the same, like plus wise you just might not.

Then she wakes up and for once it’s morning and she has slept right through without any of the usual waking up.

The next time H comes to the house George isn’t expecting her and is in her mother’s study. She has sneaked in there where she’s not meant to be and is sitting at the desk with the big dictionary open looking to see if LIA, without the R, happens to be a word in its own right.

(It doesn’t.)

She looks at the list of words that begin with LIA. She imagines her mother in the dock in a courtroom. Yes, your honour, I did write the word above his head, but I wasn’t writing the word you imagine. I was writing the word LIANA and a liana, as I’m sure you know your honour, is a twisting woody tropical plant which can hold the weight of a man swinging through the trees, familiar to us for instance from the Tarzan films of my youth. From this it should be easy to deduce that the word I was writing would have been meant finally as a compliment.

Or

Yes, your honour, but it was going to be the word LIATRIS, which your honour may or may not already know is a plant but can also mean a blazing star, from which it should be easy to deduce etc.

No. Because her mother would never have lied like that about what she was writing. Lying and equivocating are what George, not her mother, would do if she’d been caught writing some word on a window above someone important’s head.

Not that her mother was caught.

Though George probably would have been.

Her mother, instead, would have said something simple and true like, yes your honour I cannot tell a lie, I believe him to be a liar which is precisely why I was writing the word.

I cannot tell a lie. It was me who chopped down the cherry tree. Now that I’ve been so honest, make me a precedent. No, not president. I said precedent.

That’d maybe be worth £5 for a Subvert, if her mother were here.

(But now that she isn’t, does that make it worthless?)

There are also the possible words LIAS, LIANG, LIARD. A sort of stone, a Chinese weight measure, a greyish colour and a coin worth very little (it is interesting to George that the word liard can mean both money and a colour).

There is the word LIABLE.

There is the word LIAISON.

( I bet its in a cathedral city up in some fancy cathedral ceiling hanging out with the carvings of the angels .

I bet its

its )

Wrong.

The wrongness of it is infuriating.

The George from after can still feel the fury at the wrongness of things that beat such huge dents into the chest of the George from before.

Читать дальше