If that film still existed it meant there was a recording of her somewhere and in it she was looking straight over their heads into the eyes of Helena Fisker.

George opens the door.

Thought you maybe weren’t in, Helena Fisker says.

I am, George says.

Good, Helena Fisker says. Happy New Year.

Henry sits up in the bed when George and Helena Fisker come into George’s room.

Who are you? Henry says.

I’m H, Helena Fisker says. Who are you?

I’m Henry. What kind of a name is that? Henry says.

It’s the initial of my first name, Helena Fisker says. The people who don’t really know me tend to call me Helena. But I know your sister. We’re friends at school. So you can call me H as well.

It’s the same initial as my first name, Henry says. Did you bring a present?

Henry , George says.

She apologizes. She explains to Helena Fisker that since their mother died whenever people come to the house they generally tend to bring Henry a present, sometimes several presents.

Don’t you get them too? Helena Fisker says.

Not as many as he gets, George says. I think they think I’m too old for presents. Or they’re more scared of trying to give me anything.

Did she bring a present or not? Henry says.

Yes, Helena Fisker says. I brought you a cabbage.

A cabbage isn’t a present, Henry says.

It is if you’re a rabbit, Helena Fisker says.

George laughs out loud.

Henry, too, clearly thinks this is very funny. He curls into a laughing ball in the bedclothes.

Your hair’s all wet, he says when he stops laughing.

That’s what happens when you walk through the rain with no hat or hood or umbrella, Helena Fisker says.

George takes her over to the bookcase and shows her the leak and the rain dripping every few minutes on to the cover of the top book on the pile.

At some point, George says, this roof will stave in.

Cool, Helena Fisker says. You’ll be able to look directly out at the constellations.

There’ll be nothing between me and them, George says.

Except the occasional police helicopter, Helena Fisker says. The great lawnmower in the sky.

George laughs.

Two seconds after she does she realizes something and she is surprised.

What she realizes is that she has laughed.

In fact she has laughed twice, once at the rabbit joke and once at the lawnmower.

The thought of it pretty much surprises her into another laugh, this time inside herself.

That makes it three times since September that George has laughed in an undeniable present tense.

The first time H comes to the house again after New Year she hands George the A4 envelope she’s carrying under her arm. She takes off her jacket and hangs it up in the hall.

George holds the envelope back out for her to take.

It’s for you, H says.

What is it? George says.

I brought you some stars, H says. I printed them up off the net.

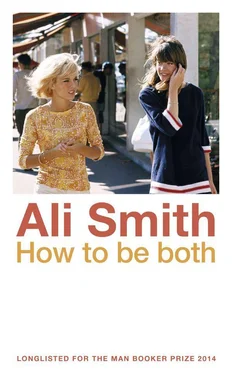

George opens it. Inside there’s a photograph on thick paper. It’s summer in the picture. Two women (both young, both between girl and woman) are walking along a road together past some shops in a very sunny-looking place. Is it now or is it in the past? One of them is yellow-haired and one of them is darker. The yellow-haired one, the smaller of the two, is looking at something off camera, off to her left. She’s wearing a gold and orange top. The dark-haired taller girl is wearing a short blue dress with a stripe round the edging of it. She is in the middle of turning to look at the other. There’s a breeze, so her hand has gone up to hold her hair back off her face. The yellow-haired one looks preoccupied, intent. The dark one looks as if something that’s been said has struck her and she’s about to say a yes.

Who are they? George says.

French, H says. From the 1960s. I was telling my mother about your sixties kick and I told her that story, the one you told in Maxwell’s class about the BT Tower and she wanted to know which singer it was and then she started looking up singers she’d liked, especially ones her mother’d liked, and she got annoyed that I didn’t know any of them and made me look them all up on YouTube. Then, when I did, I thought this one (she points at the blonde one) looked a bit like you.

Really? George says.

My mother says they were both huge stars, H says. Not together, separate stars. They both had huge careers and changed the music industry in France. My mother went on and on about it. Actually she went off on a tangent, I told her about your mother at one point and she went all (H starts doing a lightly French accent) it is not fair for your friend, she is not going to get the important boredoms and mournings and melancholies that are her due and are owing to her just from being the age that she is, for now it will be interrupted by real mournings and real melancholies , anyway then I thought I’d bring the picture round to get away from her going on about it, then I thought I could ask you if you want to come out to the car park with me.

A car park? George says.

The multi-storey, H says. Want to come?

Now? George says.

I guarantee it’ll be really boring, H says.

George looks out of the window. H’s bike is leaning against the wall outside. Her own bike is in the shed still with last summer’s puncture. In her head she can see the tyre useless in the dark, the bike all lopsided against the gardening stuff.

Okay, she says.

They walk towards town with H wheeling her bike between them. When they get to the multi-storey George goes towards the lift door but H puts a finger to her mouth then points at the glass-walled security cubicle. There’s a man in a uniform in it with what looks like a newspaper for a head. He’s asleep under it. H points at the fire doors that lead to the stairs. She opens one of the doors with great care. It’s heavy. George props it with her foot. When they’ve both squeezed through, H eases it closed.

It’s a Monday night in February so there aren’t many cars. There’s only one solitary four-wheel drive parked up on the top deck, which is the roof of the car park and is open air, open to the sky, its concrete flooring wet from the rain and shining under the car park lights.

George and H lean as far over the top deck wall as they can (they make them this high so it’ll be less inviting to suicides, H says). They look down at the roofs of their city, the streets near-empty, shining too after the rain. An occasional car passes below. Nobody much is out.

This is what the town will look like when I’m dead too, George thinks. And if I were to jump, right now? Nothing about it would change. They would just clean up whatever mess I’d make and then the next night it would rain or not rain, the street surface would be shiny or matt, the occasional car would pass below and on the busy days the traffic would queue up down there to park in here so people could go to the shops, this deck would fill with cars then later it’d empty of cars, and the months would pass one after the other, February coming round again, and again, and again, February after February after February, and this historic city would carry on being its historic self regardless.

She stops thinking it because H has fetched, by herself, by dragging it up the steps in the stairwell, the shopping trolley they passed on the way up which someone’d abandoned at the lift doors on the floor below.

It’s quite a new trolley. It crosses the concrete without too much noise.

Here, H says. Hold it steady for me.

George holds it still while H climbs into it, no, not so much climbs as vaults. All she has to do is take hold of the side and flick herself into the air and she’s in. It is pretty impressive.

Читать дальше