Neighborhood, your streets are narrow

Frost and gray skies

Life is dark, day and night

For company, cloudy skies

Patience.

Have patience and the sky will become more

blue

Have patience: a lemon tree will bloom in the

neighborhood.

But that wouldn’t be till the summer. For now, this lunchtime, with all the birds in the trees mad with spring outside, I poured my coffee into the favorite mug, came through to the study, curled myself into the armchair and I read to the end.

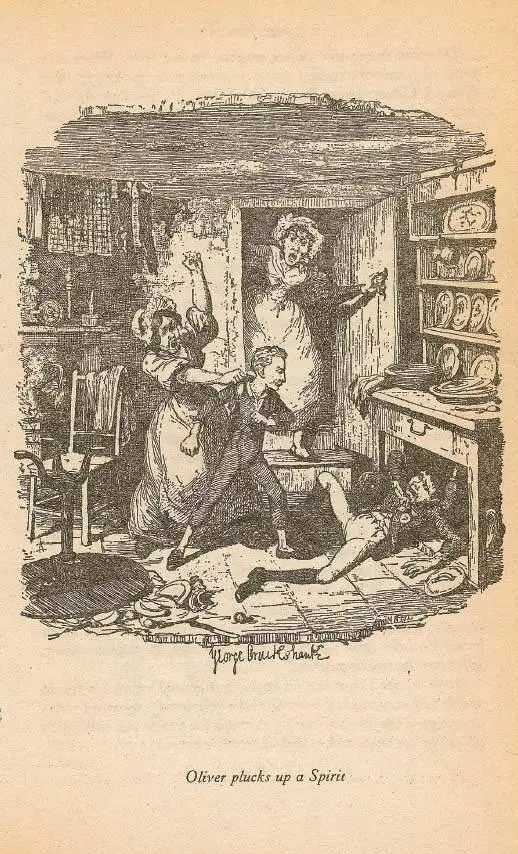

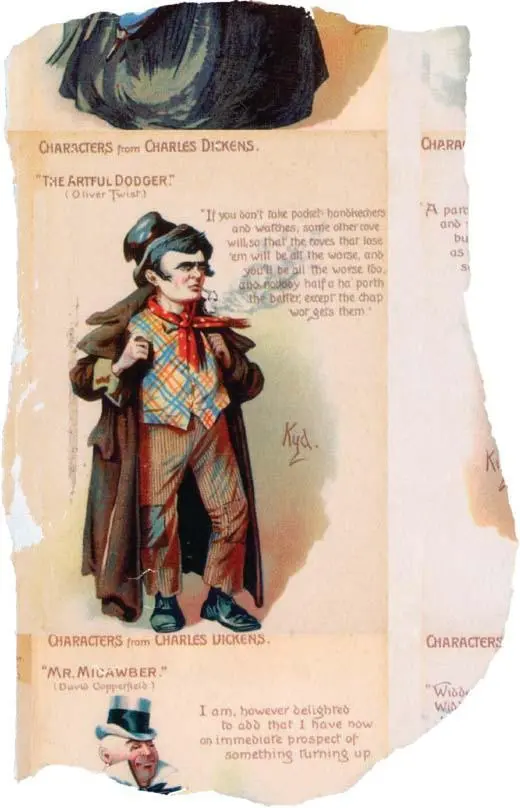

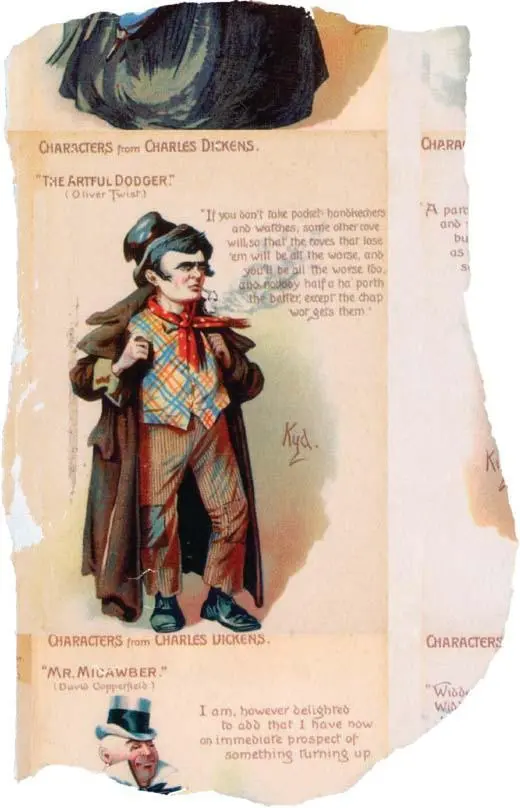

Then I went back nearly a hundred pages and read again the bit where the Artful is in court and how after his trial he leaves the courtroom ‘establishing for himself a glorious reputation’ as he goes; ironic, of course, and at the same time completely true. In fact, glorious reputation is the last we hear of him.

You know what I really like? I said out loud in the empty room. It’s how Dickens, when he sums up near the very end of the book what’s happened to all the people in the gang, well, in the whole book, when he lists the characters one after the other and tells us what became of them, he never directly mentions the Dodger. It’s like the Dodger’s given not just the story the slip, but given Dickens the slip too.

(Who did I think I was talking to?

You.)

Some sources used in the writing of these talks

The epigraph is from the Song of the Flow of Things in Bertolt Brecht’s Man Equals Man (1926).

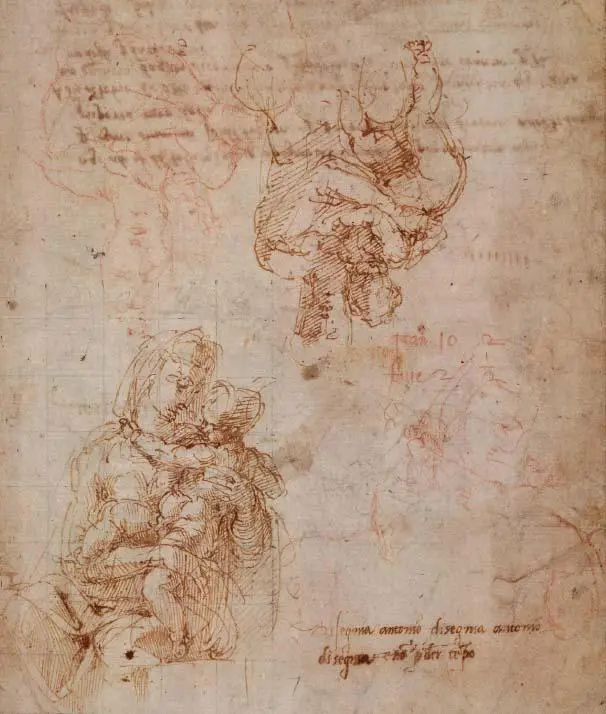

On time

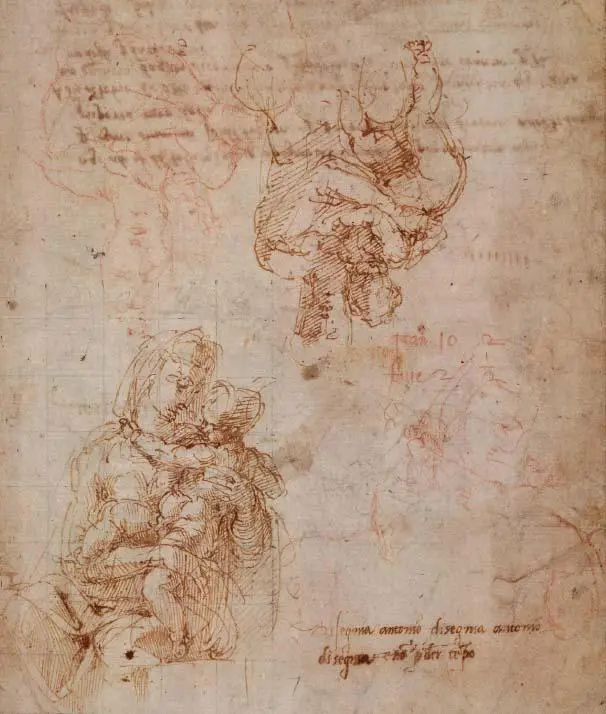

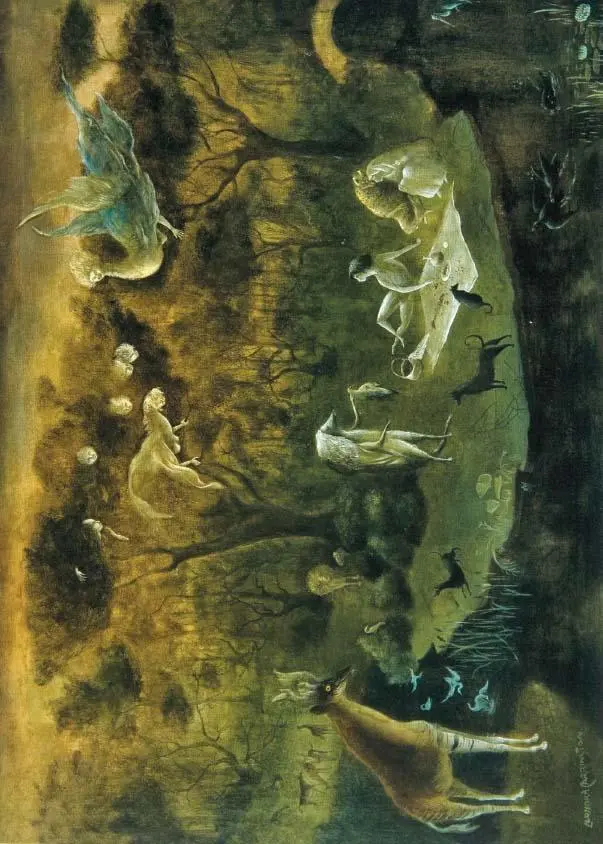

Angela Carter resees Blake’s Tyger as a pajama case in her 1978 essay, Little Lamb Get Lost; George Mackay Brown imagined the land of Tir-Nan-Og in midsummer of 1981 in one of his newspaper columns for the Orcadian, collected in the 1992 volume, Rockpools and Daffodils; Walter Benjamin writes about the storyteller’s authority in his 1936 essay, The Storyteller; the quote from Margaret Atwood about time comes from her 2002 book of lecture-essays, Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing; all the Shakespeare references here to Time with a capital T come from the sonnets, and the two lines quoted in full are from Sonnet 64. The letter by Katherine Mansfield is dated 1909, to an unidentified recipient; in it she is worrying about the strange and changeable nature of her heart. Michelangelo’s urgent instructions to his assistant, Antonio Mini, can be found on a Virgin and Child sketch held in the British Museum; the Montale/Morgan translation comes from the poem called Brief Testament; Three Wheels on My Wagon was written by Bob Hilliard to music by Burt Bacharach in 1961 and was a hit for the New Christy Minstrels in 1962; the quote from Victor Klemperer comes from the volume of his diaries entitled The Lesser Evil; and Jackie Kay kindly wrote http://www.google.co.uk especially for these talks.

On form

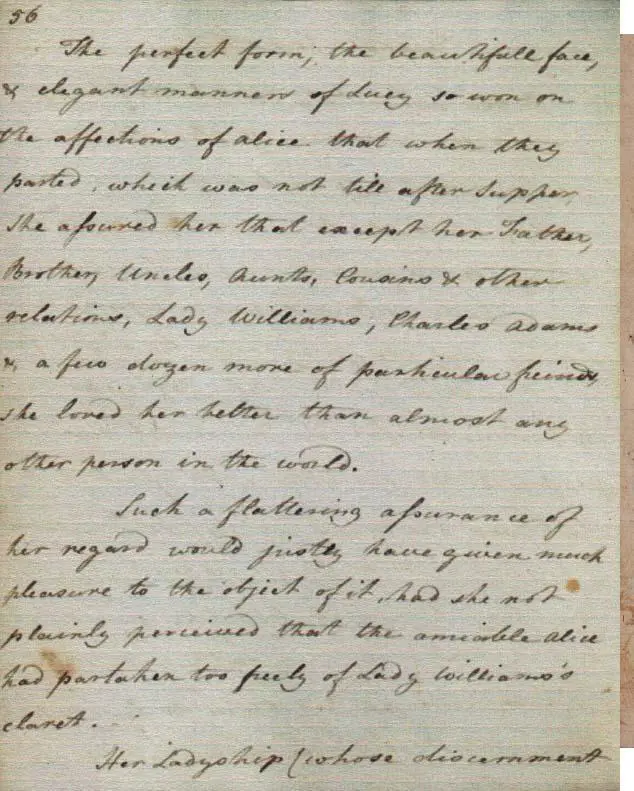

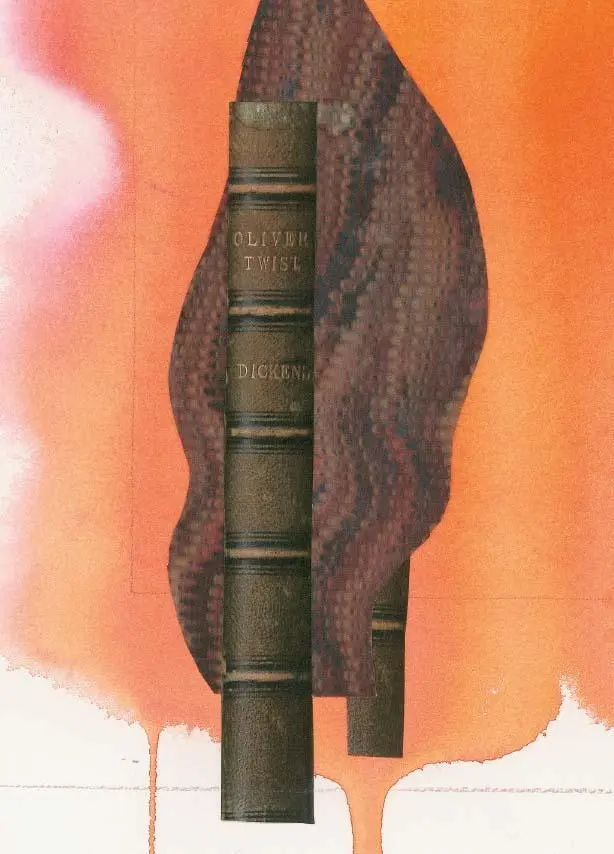

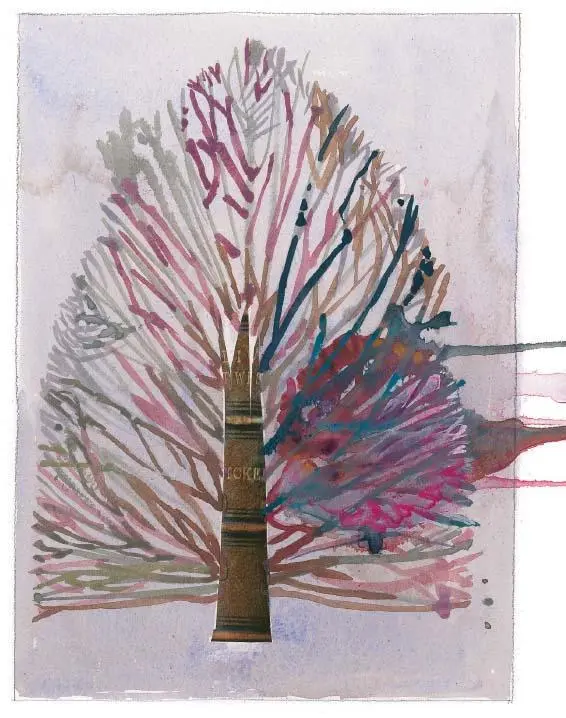

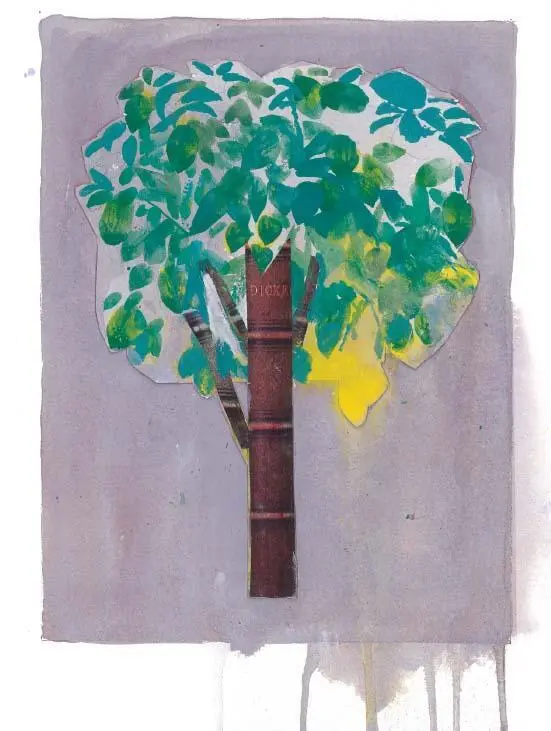

begins with a poem made of lines from famous poems by, consecutively, Wallace Stevens, Emily Dickinson, William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Stevie Smith, John Keats, Dylan Thomas, WB Yeats, Sylvia Plath, WH Auden, Edward Thomas, and Philip Larkin. Ted Hughes meets Ovid in Hughes’s 1997 collection, Tales from Ovid; the Graham Greene comment on Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida comes from Shirley Hazzard’s book Greene on Capri (2000); its original source is an essay on British dramatists which Greene wrote in the 1940s. Later in this chapter I quote again from this memoir (whose slimness belies its richness), from a conversation Hazzard had with Greene about the impression reading War and Peace made on him. Thom Gunn’s definition of poetry comes from My Life up to Now, the autobiographical introduction to his bibliography in 1979; this can also be found in his collection of essays, The Occasions of Poetry (1982). It’s Kasia Boddy, decades ago, who drew my attention with her usual unique, generous, and fruitful eclecticism to the confluence of Shakespeare and Stevens in Morgan’s Not Marble; the Horace reference comes from the Odes, III.30; Woolf’s quote about the born writer and the husks of words comes from her essay on Oliver Goldsmith; the heart as metaphor, or not, comes from Elizabeth Hardwick’s 1979 novel Sleepless Nights. I’ve purposefully misquoted the line from the song Smile, for which Charlie Chaplin wrote the tune (it was music that featured in his 1936 film, Modern Times); the true first line is slightly different, though I’d bet it’s more often remembered as this misquote. The lyrics for Chaplin’s piece of music were written by John Turner and Geoffrey Parsons nearly twenty years after Chaplin composed it. The lines about the singing bird and the apple-tree are from Christina Rossetti’s poem A Birthday; the Ovid references a paragraph later come from the stories of Apollo and Daphne and Philemon and Baucis, in Metamorphoses; the quotations from Pound come from his poem The Tree, and from New Age, January 7, 1915; the lines about the star-eaten blanket of the sky come from the poem The Embankment, by TE Hulme. This is Katherine Mansfield on the hotel’s-worth of selves: ‘True to oneself! Which self? Which of my many — well, really, that’s what it looks like coming to — hundreds of selves. For what with complexes and suppressions, and reactions and vibrations and reflections — there are moments when I feel I am nothing but the small clerk of some hotel without a proprietor who has all his work cut out to enter the names and hand the keys to the willful guests’ (The Katherine Mansfield Notebooks, Vol. II, ed. Margaret Scott, University of Minnesota Press, 2002). The quote from Woolf is from the last pages of A Room of One’s Own; the one from Yayoi Kusama, translated here by Ralph McCarthy, comes from her 2002 autobiography, Infinity Net. The quotations from Italo Calvino are from Six Memos for the Next Millennium, translated here by Patrick Creagh; these stories about Cézanne — and many more — can be found in Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art by Ambroise Vollard, which I read in the translation by Harold L. Van Doren published in 1924; and it’s the character of the Beadle, Mr. Bumble, who lays claim to naming Oliver Twist alphabetically.

Читать дальше