“Peep This” swaggered from the jukebox, and people shrieked as they recognized the opening sample. Every couple of years a hip-hop song invaded the culture with such holy fervor that it revealed itself to be a passkey to universal psyche, perfectly naming some national characteristic or diagnosing some common spiritual ailment. You heard the song every damned place, in the hippest underground grottoes and at the squarest weddings, and no one remained seated. “Peep This” possessed exactly such uncanny powers, and in the way of such things completely killed off a few choice slang words through overexposure. When grannies peeped this or peeped that from the windows of their retirement-community aeries, it was time for the neologists to return to their laboratories.

Just a few bars into “Peep This” and leis were bouncing off the ceiling. That sublime and imperative bass line, he told himself. Behinds jostled tables and chairs to make more dancing room. Beverley pulled him up. He did not beg off or point dejectedly at his bum leg. Truth be told, like everyone else, he loved “Peep This.” It had taken months of brief exposure at the corner bodega before he realized that the song had attached itself to his nervous system. He was more or less powerless against it, a blinking automaton. In the Border Café, he swayed and nodded to the directives of the bass line, nothing too extravagant, but he was, nonetheless, dancing.

New Prospera. New beginnings, blank slates. For all who came here. Including him. No, he was not about to hock all his possessions and hightail it out west, but things would not be the same when he got back home. The old ways would not hold. Would he go back to work, reclaim the mug and office that was rightfully his? His thoughts alighted on his cuff links. When was the last time he had seen them? Where the fuck were they? He looked around at his new cohorts, into their sweaty, peppy faces. The name was what they needed. Narcotic. Hypnotizing. New Prospera was the tune people knew the second they heard it, the music they had danced to all their lives. That was the point of a name in this situation: to set up a vibration in the bones that resembled home.

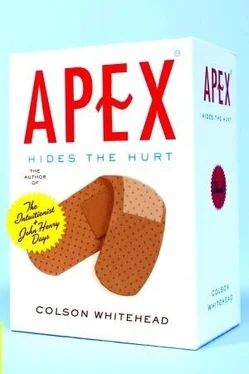

He snapped his fingers in time to the famous bridge of “Peep This,” that dangerous territory that often compelled the weakest dancers in the room to unfortunate excess, but this bunch did not take the bait. Which made this a bona fide miracle in process. He pictured “Peep This” as the soundtrack for an Apex ad, wherein one by one his current co-partiers pulled back their sleeves or pants legs to reveal perfectly camouflaged wounds. Slightly roughed up by life’s little accidents but somehow better for the experience. He bebopped his head to the beat. Was he supposed to honor the old ways because they were tried and true? Fuck all Winthrops, and let their spotted hands twist on their chests in agony. And forget the lovers of Freedom. Was he supposed to right historical wrongs? He was a consultant, for Christ’s sake. He had no special powers.

He snickered, mulling over what Goode and Field would do in this situation. The Light and the Dark. Goode announces in preacherly tones, “We are Americans and the bounty of American promise is our due. It is what we worked for, it is what we died for, and we call it New Prospera.” The audience moving their heads in solemn amen and hope. To that sweet music.

He pictured Field, but the vision was dimmer. He saw a lone figure, withdrawing into shadow after delivering a grim, pithy “Where you sit is where you stand.” And really, what the hell were people supposed to extract from that?

The song ended. The librarian tickled him under his ribs and beat it to the bar for refills. Jim Lee appeared, mopping his brow with his T-shirt. There were only a few sips left in his glass — another hour had passed. Jim said, “What do you think?” which in retrospect could have meant any number of things, but in that moment was interpreted as the latest inquiry into the town’s name status. And this time he had an answer.

The jukebox was quiet, and he seized the opening, shouting, “I have an announcement to make! I have an announcement to make!” Everybody turned. Jack Cameron excavated a drunken bellow from deep in his stomach. Leis slapped his face, hurled from all points. An inexplicable brassiere zipped by.

So encouraging. These people understood him. He would deliver his ruling and be done with it. His ticket back home. “Okay, okay! People have been asking me all night if I have come to a decision. About the whole name thing. Well, I have.” He put a hand on Jim Lee’s shoulder and climbed onto a chair. He looked out into the room. He cleared his throat. Steadied himself. He met Beverley’s gaze and smiled foolishly. Certainly the table was stable enough, and would heighten the drama. So he used bony Jim Lee as a cane, and clambered up on the table. Someone threw a lei up at him and he caught it. He held it in the air and they hollered, one or two among them flicking their Bics and holding them up in tribute.

To be done with his stupid exile. Why had he removed himself so completely from those things that others cherished, with his needless complications and equivocations. It was all very simple, after all. Why did he need to make it so difficult all the time. So dark in outlook all the time, frankly. And he felt like being frank, above the fray as he was, astride the tabletop, on the layer of polyurethane covering the map of Cozumel.

It was a nice moment. Someone should have taken a picture. Nice composition, what with the multicolored streamers crisscrossing the ceiling and his triumphant manic face. If only someone had taken a picture.

He was about to speak when something in him gave way, and his bad leg jackknifed with such speed that he was on the floor in an ugly mess before anyone could catch him. In the ensuing hubbub, he fixated on one exchange in particular:

“What happened?”

“He slipped.”

. . . . . . . .

He was weak and feverish. Caught in the fangs of the big fear, shaken back and forth. His brain worked as unsteadily as his feet, had wires hanging out after someone ripped out that important piece of hardware. It was cooler outside, much cooler than inside the banquet hall, and this soothed him for a few blocks. The streetlights and traffic lights and neon lights all had halos, and seemed beacons summoning him. But so many different directions: How was he to know which way to go?

He was aware of his body as a shell. Fragile, thin as excuses. A vessel containing the dust of his essential him-ness, which would be lost when the vessel failed. Well, that was the way of the world. For a time he was fixed in his body, stuck and named and fixed in place, but one day that would not be the case. One day only his name would remain, on a tombstone or etched onto an urn, marking his dried bones or ashes. A delivery truck almost clocked him as he stumbled into the crosswalk. Pay attention, he told himself. Pay attention: accidents come out of nowhere to teach you a lesson. He should be looking out for that which strikes from above, things like lightning that fall from the sky to instruct through violence.

Blubbering in his fever. On the buildings the names hung there as if by magic. (The billboards were attached by bolts and brackets.) In the windows of stores they were spread out in an unruly mess, this pure chaos, sick madness, as if tossed into a garbage heap. (Items were arrayed in orderly, enticing displays.) And the citizens walked the streets, alone, in comfortable pairs, in ragged groups, with their true names blazing over their hearts, without pride or shame, plainly, for this new arrangement was just and true. (Strangers passed him, and he passed strangers.)

Now he was in the Crossroads of the World, as this place had come to be called. The names here were magnificent, gigantic, powered by a million volts and blinking in malevolent dynamism. Off the chart. The most powerful names of all lived here and it was all he could do to stare. He had entered the Apex.

Читать дальше