“I thought you were the cutest boy out here,” she said. She stopped. “What happened to you?”

“What happened?” I cocked my head back because I felt that was the appropriate response to such a statement. Insulted, etc. What a normal person would do.

“No, I don't mean it like that,” she said, chuckling. Her fingers brushing down my arm. “I mean, you just always seemed so happy all the time. You had that Planet of the Apes pajama top you liked to wear as a shirt even though it was the daytime, and you were always laughing with Reggie at everything.”

“Now I'm all angry and mad?”

“I didn't say that.” She bumped me with her hip.

Huh.

We were outside Marv's house. It was a rancher with a long flat roof, painted a robin's-egg color that was what radiation would look like if you could see radiation. Light came from the basement window, through the dirt splashed on by the rain. I thought about Rusty Potz, the WLNG afternoon guy. He coated his voice with so much reverb it sounded like he worked underground, only getting fresh air during one of their remote feeds from the Sag Harbor Masons' Annual Fish Fry. (“Tickets are still available at the Municipal Building on Main Street.”) From his hepcat rock-'n'-roll patois, I pictured him with a white beret and satin baseball jacket, standing in front of a few signed photographs of him shaking hands with Bill Haley and His Comets, the Yardbirds, and sundry crooners dressed in matching cardigans. He worked alone in his dungeon, stirring the cauldron, concocting longing for his listeners.

WLNG didn't play hip-hop, of course, outside the occasional spin of “Rappin' Rodney.” That's where Marv and his underground operation came in, down in his basement. Marv was an in-betweener, a few years older. He was “street-smart,” wielding the latest styles with the unself-consciousness that came from actually being that elusive thing: unimpeachably down. Once he hit high school he stopped coming out, to commit himself to the B-boy lifestyle. He was the first person I met with two turntables. One turntable, you liked music. Two turntables and you were an artist. In the summer of '81, he cut up “Good Times” like a true acolyte of Grandmaster Flash, slashing the fader back and forth in a three-card monte panic, rubbing out a few tentative scratches, zip zip. The famous bass line strutted like a hustler around the room in a beige jeans suit, with an Apple Jack on his head: What can I get up to now? He didn't have that many records in his milk crate, but they all had the name of the song blacked out with Magic Marker. “That's so no one bites me,” he explained. We crowded around, watching his magic. After a while he'd say, “I'll see you later — I gotta practice,” and he was alone again in the cement room, working solo in his bunker like the WLNG guy. You deliver the news and you do it alone.

Marv's mother still came out. She'd probably covered his DJ tables with second-home basement crap, old sewing machines and spiderwebbed boogie boards. The stuff you keep around because you convince yourself that one day you might use it again. We all know how that ends. Melanie remembered Marv from the old days and I told her that he didn't come out anymore because he thought Sag was for kids. She told me about her cousin, who was a big DJ at some clubs in the Bronx, and then said she remembered when Marv's mother threw a birthday for him and invited all the kids. One of the big kids started chasing Marcus around the picnic table trying to noogie him, and Marcus slipped and crashed into it, sending the birthday cake flying. “It went all over the place.”

I remembered that day. Everybody wearing some form of multicolored striped article of clothing, that was the rule. Reggie attempted to salvage a clean chunk of cake from the ground. It was something he might do, gather what he could from the mess. Make sure he got his. But I didn't remember Melanie. I tried to put the scene back together, picture the faces under the cardboard party hats. I couldn't see hers. But she had to be there. Was that the day she kissed me? Hovering at my side all afternoon, brushing her arms against me by accident. Then leaning over. I was her husband. It must have happened. Where did it go?

That fucking song scrabbled in the cage of my head, shaking the bars:

For there are you, Sweet Lollipop

Here am I with such a lot to say, hey hey

Just to walk with you along the Milky Way

To caress you through the nighttime

Bring you flowers every day

Oh, Babe, what would you say?

Like I said, I'd been dinged, but good. Now it stirred up all the silt at the bottom. Bringing me around. It was my first kiss I was remembering, that lost day I recovered. I saw it clearly. The song must have come through the kitchen window that day, the radio set on WLNG when Marv's mother checked the weather report. She left it there at 92.1 and the enchantments followed. The big kid tormenting Marcus was Big Bobby, no, it was Neil, Neil the pervert who one time climbed up the roof of our porch to peep on Elena and got caught. My parents and his parents didn't talk for two summers. He was premed at Morehouse now, that was the word. Marcus smashed his skull into the table and things went into slow motion as the Carvel cake and Dixie plates and Hi-C tumbled through the air. Someone pulled on my arm, whispering, “Benji.”

It seemed impossible not to remember something like that. The first time a girl put her lips on yours. What kind of chump forgot being a five-year-old mack? I would've coasted on that for years if I'd known. But I did know. I was there. What put it out of my mind? I looked at Melanie's profile, the coast of her nose and mouth and chin. She was one of us. A Sag Harbor Baby.

We were at the corner, the end of Richards Drive. The natural destination was town. Where we'd run into somebody and then it wouldn't be just me and her anymore. There was nowhere else to go.

Melanie said, “There it is.” I turned and saw the old place up the street and I knew it wasn't her at all.

I will take the world at its word and allow that there are those who have experienced great love in their lives. This must be so. So much fuss is made over it. It follows that there are others who have loved but came to realize over time that what they had was merely the shadow of a greater possibility. These settled, and made do, or broke things off to continue the search. There are those who have never loved, and they walk through their days grasping after true connection. And then there is me. Ladies and gentlemen and all of you at home just tuning in, the angel of my heart, my long lost love, was a house.

There she was, my Sweet Lollipop. Posing coyly behind the old hedges, just a wedge, a bit of thigh, visible behind the trees. When people were inside at night, the light from the windows splashed through the leaves and branches, diluting the darkness. It was always a comfort rounding the corner and seeing that after you'd been running around all day. Soon you'd be inside with everyone else.

The windows were black. Since the swap, where we got the beach house and my aunt kept the Hempstead House, she rarely came out. Occasionally she gave the keys to friends for the weekend, and it was disturbing to see an alien vehicle in our driveway. Ours, even though it wasn't anymore. My mother would call her sister to double-check that everything was okay. I hadn't seen anyone there all summer.

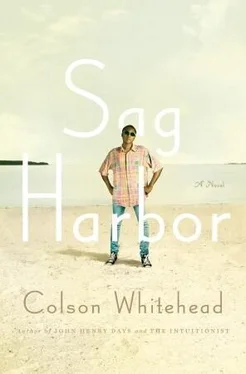

“Let's go see,” I said. She walked with me without hesitating. The house my grandparents built was a small Cape Cod, white with dark shingles on the roof and red wood bracing the second story. It was made of cinder block, stacks of it hauled out on the back of my grandfather's truck. Every weekend he brought out a load, rattling down the highway. This was before they put in the Long Island Expressway, you understand. It took a while. Every weekend, he and the local talent put up what they could before he had to get back to his business on Monday. Eventually he and my grandmother had their house. Their piece of Sag Harbor.

Читать дальше