“This sucks!” she said.

I unlatched the windows. She said, “Are you crazy?”

“No, look — the roof.” I saw her frown at me. “It's totally safe.” Then whispering: “Me and Reggie used to go out here all time.”

We heard the front door creak open. That creak! I threw a leg outside and pulled my body through. Melanie banged her head on the frame and said, “Ow!”

“Shh!”

“Ooh!”

“Shh!”

We stepped over the twigs and acorns lobbed from the trees. I led her to the side of the porch away from the driveway. “Now what?” she whispered, looking over.

“We gotta jump for it,” I said. More action-flick dialogue. The edge of the canyon, the mercenaries' jeep bouncing closer. The kissing had jostled something loose, some he-man narrative.

“I'm not doing that.” A hand downstairs discovered the lamp in my parents' former bedroom, throwing light onto the grass.

“We have to,” and I jumped. It really wasn't that far, and my legs knew what to do after so many rehearsals. I'd seen myself jumping off the porch to escape a raging fire or a mass of zombies moaning up the stairs, but never thought I'd be looking up at a girl, saying, “I'll catch you.”

I didn't. She knocked me into the dirt like an Acme anvil. She yelped. Loud enough for the person inside to hear. Then we ran. Along the side of the house, dashing across the front yard and into the street. I heard someone yell after us, and snuck a glance back to see a silhouette on the front stoop. But we were around the corner with a quickness.

• • •

THE NEXT DAY I SAW MELANIEthrough the window of the grill. I took my break. She sat on one of the benches, rubbing her sandals in the dirt, pretty toes poking out. She watched me walk over. A limousine prowled up the lane between us, a slow black shark, and I waited for it to pass. Her expression did not change. I gave her the ice cream I'd scooped for her. Mint Chocolate Chip in a Waffle Cone with Rainbow Sprinkles, what I'd heard her ask for all those times when she came in to see Nick while my head was down in the vats. She said, “Oh, thanks,” and extended her soft tongue to the ice cream. “It's hot out today.”

I told her that my aunt had let one of her employees use the house for the weekend. She said, “That's okay,” and looked past me and Nick materialized and slid up next to her, circling his arm around her and slipping his fingers into the tight pocket of her jeans. He didn't ask about the cone. That was that.

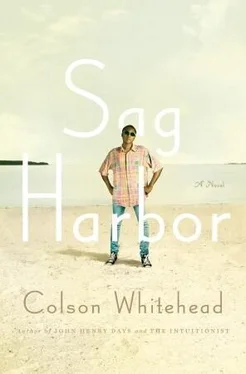

My aunt sold the house a few years later. When I asked her why she'd do such a thing, she told me, “I never went out there. What was the point of holding on to it?” I was appalled, but you know me. I was nostalgic for everything big and small. Nostalgic for what never happened and nostalgic about what will be, looking forward to looking back on a time when things got easier.

She sold the house to that brand who keep it up, diligently mailing checks to the lawn guy and the guy who turns on the water at the start of the season, but who never seem to come out. They haven't done a thing to it, repainted it or anything, so it looks like it always did. When I walk by there now, I could be staring at a photograph of when my grandparents just finished it, them stepping out into the street to admire what they'd accomplished. Or the first time I saw it when I was a baby, aloft in my mother's arms. Far away, then getting bigger and more real the closer we get to it.

It looks like it's waiting.

THE BLACK NATIONAL ANTHEM

THE BOYS LINED UP TO RACE. THEY DOUBLE-KNOTTEDtheir shoelaces, the sad noodles gone gray from a summer of tramping, and pulled up their tube socks, which slowly fluttered down their calves and ankles for lack of elastic. They nosed their sneakers as close to the line as possible, newly gung ho about millimeters and the small advantages that get us through life. The red chalk disappeared over the busy day as feet treated it like the dust it was, sweeping it away into the beyond, but for now it was a respected border, cordoning off the picnic tables and red-and-white coolers and spectators from the playing field in the middle of the street. The anticipation. The boys unwrapped their favorite scowls and glares to psych out their competitors. Any second now. And then the false start, from that kid who was you and me. Eager to begin and nervous with everybody's eyes on him and then fucking up. “Dag,” the other boys groaned, shaking their legs and gathering themselves anew. Angry as if the whole summer were at stake.

The girls went first. The 5-to-7-year-olds who believed the secret of speed was in the face, in the fierce, scrunched expressions they pushed ahead of their bodies, and then the 8 to ios, quicksilver in ponytails, and finally the gawky and glorious 11 to 12s, racing for the last time, sprinting desperately into teenage preoccupations and fleeing the girls they had been. Mr. Grady raised his starter pistol, his other hand cupping the black stopwatch bobbing on his chest. Mr. Grady, year after year. With his brown-and-red skin — half Cherokee, so he claimed — and skinny arms and legs and potbelly. He was a notorious drinker among unapologetic drinkers, legendary for his annual pass-out in the driver's seat of his dark Cadillac, as the radio played and the motor hummed, too out of it to walk up to his front door. This was his one sober afternoon of the season. He had a duty. His son had been a natural athlete and everybody said he could have been in the Olympics if he'd wanted to, he was that good. But then he fell in with the wrong crowd. After the races, Mr. Grady hit the rum punch in front of the Delaneys' with a quickness, to close the distance. Mr. Grady with his trembling arm sticking up in the air an authority only kids were stupid enough to obey.

They ran to prove who was the fastest, the most worthy, to settle three months of scores, they ran for their parents, who did or did not watch from the sidelines and did or did not cheer them on. First, Second, and Third Place got medals. Mr. Gordon, the chairman of the Sag Harbor Hills Improvement Association, knew a guy in Wainscott who knocked them out at a reasonable price. The winners wore the medals all day, pinned to their cotton-poly shirts, looking down to marvel at them when a cloud passed the sun or they shivered from some internal tremor, lifting them up for grown-ups to examine after admiring remarks. Clive always came in First when the mess of us used to pell-mell down the street, except for the year when he twisted his ankle, and he still had them up on the wall of his room, a blue row roused by the draft whenever you opened the door. I never won, but I never expected to. It was okay.

We were the big kids at the Labor Day party now that Elena and her group were off. Watching from the sidelines, jawing, disdainful. We were down to a skeleton crew. Me and Reggie. NP and Nick, who was staying out in Sag in his weird exile after the rest of us picked up our stakes. Time was, we never missed this day. But other things were more important now. Clive and Bobby and Marcus were already in the city. We were growing into those who went away.

When Reggie and me made it over to Sag Harbor Hills, NP and Nick were talking to a tall boy with hazel eyes and rusty curls. His name was Barry David. He wore gray Lee jeans, crossing his arms over a striped blue-and-crimson Le Tigre polo. Also, a constant smirk. He looked familiar and I figured him for someone's city buddy out for the big day, or a Southern relative up for his annual dose of bourgiefication. Labor Day, all sorts of strangers left their mark.

We were learning that it wasn't as much fun watching the races when you weren't running. If the girls were still out, we would've been diverted by social performance, but Devon and Erica had already gone back to New Jersey, and Melanie and her mom's rental was over. Rent your house out for August, sure, but you'd be a fool to give up Labor Day. Watching the little girls tackle the street, it was clear that our group's gender disparity was only a statistical blip — the next group was well stocked. Elena's group had been well balanced, too, and with them no longer coming out, the poverty of our situation was even more apparent. There would be no fashion show this year, and maybe the next few, until the next crop of girls transferred their interests from hopscotch to runways.

Читать дальше