Though the noises of Arcadia are flat, the fruit and vegetables have never seemed so polished and so uniform. The traders, beneath their matching awnings, seduce the passers-by with produce of the gene-bank and the science farm, enhanced by Spray-Dew, Frost-Ban, and by packaging. Recessed orange lights warm and flatter every radish, every grape, every hybrid superfruit. Together with the onions and the swedes, are Kingquats, a kumquat bigger than a plum and every part of it — the peel, the pith — is edible. And there are orange grapes, and bananas from Barbados shaped like avocado pears. And avocado pears without a stone. And lab-grown lettuces (red or green or white). And glasshouse broccoli with flower-heads as big and tight as cobblestones, achromatic rhubarb force-grown under fluorescent lights, and bio-technic aubergines which some chemist-gardener has artificially bloated in dioxide pods. Young men in search of romance can still buy their loves a courting quince, just as before, but more romantically presented in a silver nest with a heart-shaped, perfumed top. Each purchase has its plastic bag, each plastic bag its coloured logo for Arcadia; each coloured logo is a dancing apple with a hygienic, grub-free smile.

If I were rich I could buy jewellery and suits from boutiques which trade side by side with salad stands. If I were ill I could select a dozen cures for my maladies from the fresh herb shop; some adder buckthorn for my bowels (recalcitrant), some juniper for failing sight, some camomile to help me sleep, some cuckoopint to keep alert my hope of finding love, some mistletoe as sedative, some poisoned laurel sap for the new Burgher’s gin. If I liked fungi (I do not) I’d have the choice of fifty sorts from Mycologia, The Mushroom Shop. Should I prepare a fritto misto for my supper from an edible bolete? Or should I select a honey mushroom or a chanterelle?

If I were looking for a gift, a set of gaudy stamps from the philatelists might take my fancy. A first edition (slightly stained) of dell’Ova’s Truismes , complete with margin notes by Pierre Loti’s bastard son. A pair of hand-made gloves. A pastry-house with stucco-marzipan and flaked walnut tiles. A T-shirt printed with my name, or any name I choose. A postcard hologram of Arcadia. Or I could light a candle for the birthday of a friend. The Market Chapel is a shop and pays the usual rent, so needs to sell as many candles as it can. Nothing is cheap, of course. Don’t rummage for your bargains here. Arcadia is built to shake out pockets, unzip wallets, cash cheques, debit bank accounts. It is a monumental Dip. Victor has created the perfect cash machine. The traders pay, on top of rents, percentages to Victor, too, like feudal peasants paying ‘overage’ on everything they sell. You see, Arcadia observes tradition after all. Something medieval is preserved intact! (If I were still the Burgher, there’d be a paragraph in this.)

Is there not cause to celebrate this new diversity, this innocent variety of goods, despite the claims of oracles and pamphleteers who say our city’s in decline — and money is the force? Yet how could those greengrocers who once traded out of sacks and boxes in the Soap Market meet the rents and standards of Arcadia? They had to modernize or close up shop. Every shop that dosed was taken up within a day, by businessmen whose visions were much looser and much wider than the soapies they replaced. Who needs so many outlets for a grape? One grape these days is much like all the rest. It makes good sense to let a market such as this diversify.

You only have to see the crowds to know these changes work. See how the middle classes flock from shop to shop, a bunch of parsley in their bags along with a batik headscarf that they’ve bought, and a piece of blue goat’s cheese. See those valet-attended dowagers braving arthritis and discretion in the couturières. See how the bars and restaurants are packed with men and women who never used the windswept bars in the old Soap Market for fear of chaos and antipathy. See the foreign faces here; the tourists who have come to witness what Fodor calls ‘the city’s triumphant fusion of modernity and tradition, order and spontaneity, Life and Art, business and entertainment’.

Of course, you will not see the night-time soapies here. The bye-laws say there can be no loitering, no unlicensed trading, no begging, no entertainment without a permit, no vehicles (including skates and skateboards), no animals (except for guide dogs), no unrestricted access to the sort who clutch a bottle or whose dress and cleanliness would strike a sour note. ‘Shop in Safety at Arcadia’, the adverts say. ‘Attended parking for two thousand cars’. There is no need to taste the city air at all, for those who drive, then shop, then drive. But who’s so fearful of the city air that they dare not venture into the open forecourts which surround Arcadia? Here an open market still survives — three stalls of fruit (no vegetables), with staff in rural uniforms of dirndl skirts, straw hats, and clogs. There’s a take-a-number, wait-your-turn lunch stand. There are greenstone benches, and official buskers more impromptu and eclectic than the bands and string quartets inside.

I browse amongst the pushcarts there. Their tenants are the city’s fireside artisans. I have the choice of jam or wooden beads or necklaces or cameos. One man sells woven bags. A woman and her dog have candles of a thousand kinds. Another deals in landscape prints and postcards of the town. I have the choice of riding on the garish carousel (restored from an original) or touring the old town by pony and trap, or visiting, with a bag of feed, the pigs, rabbits, goats, and llamas of City Farm. I also have the choice of sitting here, bathing in the bounce-light of Arcadia, or going back to work. I would return to work, except that life is comforting here, and entertaining too. It’s fun to watch the browsers shop, to watch the drama of the doorstaff turning back a drunk or turning out a bearded man with leaflets and a coat weighed down by badges. It’s better fun than work to watch the ‘flamingoes’ operate their upturned litter scoops so that the market site is clean enough — if it were not against the market law — to sit upon the ground and doze.

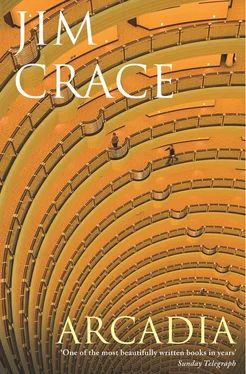

It is, of course, the spirit of research and not distaste for work that takes me strolling round the wind-stroked, whistling outer rim of Arcadia. The Glass Meringue indeed. The Lobster Trap. The See-through Octopus. The Pumpkin. It has a hundred names. But one has stuck amongst those people rarely let inside or rarely rich enough to browse and buy. They call the place Fat Vic. It’s Big Vic’s plumper sibling. One stands, one squats. They are the city’s strangest twins.

I come at last to Victor’s birthday gift, the statue cast in bronze, commissioned by the merchants of the Soap Market. The move amongst the bleeding hearts, some time ago, to pull it down and put a statue up for Rook, has come to nothing. Victor’s birthday gift survives. A woman sits cross-legged before a bowl. The artist has welded real coins inside. The woman has an infant at her breast. Its eyes are open wide, and fixed upon Arcadia. There was a time when children clambered over her, when office-workers used the plinth for lunch, when young men wrote the names of their sweethearts in felt-tip along the woman’s arms, or coloured in her nipple, darkly. But, pretty soon, they railed her and her infant in. The statue’s called The Beggar Woman and Her Child , but we all know it as The Cage .

So this is Em. And this is Victor, an infant at the breast. They are so still, you’d think their abject happiness could never end. Yet end it did. In flames. And here she — resurrected — is. Too rigid now to take the painted cart, piled high with melons — honeydews, casabas, cantaloupes, and musks — and far too late to set off, as she had promised, towards the city hems where blue fields match the sea-blue sky, with her small son her only passenger. I have the first line of his life: ‘No wonder Victor never fell in love.’

Читать дальше